In the summer of 1536 his state of exhaustion became alarming. His last letter is dated June 20, and subscribed thus: “Erasmus Rot. ægra manu.” He died July 12, in the 59th year of his age, and was buried in the cathedral of Bâsle. His friend Beatus Rhenanus describes his person and manners. He was low of stature, but not remarkably short, well-shaped, of a fair complexion, grey eyes, a cheerful countenance, a low voice, and an agreeable utterance. His memory was tenacious. He was a pleasant companion, a constant friend, generous and charitable. Erasmus had one peculiarity, humorously noticed by himself; namely, that he could not endure even the smell of fish. On this he observed, that though a good Catholic in other respects, he had a most heterodox and Lutheran stomach.

With many great and good qualities, Erasmus had obvious failings. Bayle has censured his irritability when attacked by adversaries; his editor, Le Clerc, condemns his lukewarmness and timidity in the business of the Reformation. Jortin defends him with zeal, and extenuates what he cannot defend. “Erasmus was fighting for his honour and his life; being accused of nothing less than heterodoxy, impiety, and blasphemy, by men whose forehead was a rock, and whose tongue was a razor. To be misrepresented as a pedant and a dunce is no great matter; for time and truth put folly to flight: to be accused of heresy by bigots, priests, politicians, and infidels, is a serious affair; as they know too well who have had the misfortune to feel the effects of it.” Dr. Jortin here speaks with bitter fellow-feeling for Erasmus, as he himself had been similarly attacked by the high church party of his day. He goes on to give his opinion, that even for his lukewarmness in promoting the Reformation, much may be said, and with truth. “Erasmus was not entirely free from the prejudices of education. He had some indistinct and confused notions about the authority of the Catholic Church, which made it not lawful to depart from her, corrupted as he believed her to be. He was also much shocked by the violent measures and personal quarrels of the Reformers. Though, as Protestants, we are more obliged to Luther, Melancthon, and others, than to him, yet we and all the nations in Europe are infinitely indebted to Erasmus for spending a long and laborious life in opposing ignorance and superstition, and in promoting literature and true piety.” To us his character appears to be strongly illustrated by his own declaration, “Had Luther written truly every thing that he wrote, his seditious liberty would nevertheless have much displeased me. I would rather even err in some matters, than contend for the truth with the world in such a tumult.” A zealous advocate of peace at all times, it is but just to believe that he sincerely dreaded the contests sure to rise from open schism in the church. And it was no unpardonable frailty, if this feeling were nourished by a temperament, which confessedly was not desirous of the palm of martyrdom.

It is impossible to give the contents of works occupying ten volumes in folio. They have been printed under the inspection of the learned Mr. Le Clerc. The biography of Erasmus is to be found at large in Bayle’s Dictionary, and the copious lives of Knight and Jortin.

From the bronze statue of Erasmus at Rotterdam.

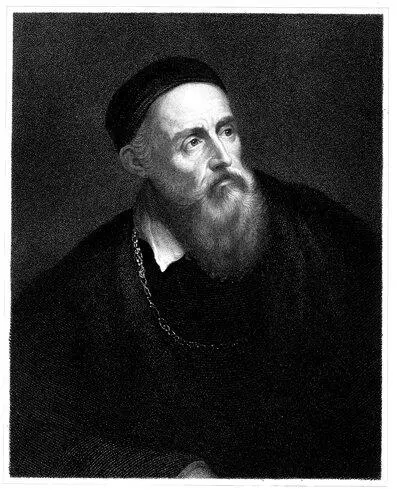

Engraved by W. Holl. TITIAN. From the Picture of Titian & Aretin painted by Titian, in his Majesty’s Collection at Windsor. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London, Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

On looking back to the commencement of the sixteenth century, by far the most brilliant epoch of modern art, we cannot but marvel at the splendour and variety of talent concentrated within the brief space of half a century, or less. Michael Angelo, Raphael, Correggio, Titian, all fellow-labourers, with many others inferior to these mighty masters, yet whose works are prized by kings and nobles as their most precious treasures—by what strange prodigality of natural gifts, or happy combination of circumstances was so rare an assemblage of genius produced in so short a time? The most obvious explanation is to be found in the princely patronage then afforded to the arts by princes and churchmen. By this none profited more largely or more justly than the great painter, whose life it is our task to relate.

Tiziano Vecelli was born of an honourable family at Capo del Cadore, a small town on the confines of Friuli, in 1480. He soon manifested the bent of his genius, and at the age of ten was consigned to the care of an uncle residing in Venice, who placed him under the tuition of Giovanni Bellini, then in the zenith of his fame. The style of Bellini though forcible is dry and hard, and little credit has been given to him for his pupil’s success. It is probable, however, that Titian imbibed in his school those habits of accurate imitation, which enabled him afterwards to unite boldness and truth, and to indulge in the most daring execution, without degenerating into mannerism. The elements of his future style he found first indicated by Lionardo da Vinci, and more developed in the works of Giorgione, who adopted the principles of Lionardo, but with increased power, amenity, and splendour. As soon as Titian became acquainted with this master’s paintings, he gave his whole attention to the study of them; and with such success, that the portrait of a noble Venetian named Barbarigo, which he painted at the age of eighteen, was mistaken for the work of Giorgione. From that time, during some years, these masters held an equal place in public esteem; but in 1507 a circumstance occurred which turned the balance in favour of Titian. They were engaged conjointly in the decoration of a public building, called the Fondaco de Tedeschi. Through some mistake that part of the work which Titian had executed, was understood by a party of connoisseurs to have been painted by Giorgione, whom they overwhelmed with congratulations on his extraordinary improvement. It may be told to his credit, that though he manifested some weakness in discontinuing his intercourse with Titian, he never spoke of him without amply acknowledging his merits.

Anxious to gain improvement from every possible source, Titian is said to have drawn the rudiments of his fine style of landscape painting from some German artists who came to Venice about the time of this rupture. He engaged them to reside in his house, and studied their mode of practice until he had mastered their principles. His talents were now exercised on several important works, and it is evident, from the picture of the Angel and Tobias, that he had already acquired an extraordinary breadth and grandeur of style. The Triumph of Faith, a singular composition, manifesting great powers of invention, amid much quaintness of character and costume, is known by a wood engraving published in 1508. A fresco of the Judgment of Solomon, for the Hall of Justice at Vicenza, was his next performance. After this he executed several subjects in the church of St. Anthony, at Padua, taken from the miracles attributed to that saint.

These avocations had withdrawn him from Venice. On his return, in the thirty-fourth year of his age, he was employed to finish a large picture left imperfect by Bellini, or, according to some authorities, by Giorgione, in the great Council Hall of Venice, representing the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa on his knees before Pope Alexander III. at the entrance of St. Mark’s. The Senate were so well satisfied with his performance, that they appointed him to the office called La Senseria; the conditions of which were, that it should be held by the best painter in the city, with a salary of three hundred scudi, he engaging to paint the portrait of each Doge on his election, at the price of eight scudi. These portraits were hung in one of the public apartments of St. Mark. At the close of 1514 Titian was invited to Ferrara by the Duke Alphonso. For him he executed several splendid works; among them, portraits of the Duke, and of his wife, and that celebrated picture of Bacchus and Ariadne, now in our own National Gallery.

Читать дальше