The literary glory of Buffon, although surpassed, or even equalled, during his life, by none of his contemporaries, with the exception perhaps of Voltaire and Rousseau, has not increased, and is perhaps materially diminished, after having been tried by the opinions of half a century. In literature, as well as in politics, as we have learnt to attach a greater value to accurate facts, have we become less captivated by the force of eloquence alone. Buffon gave an extraordinary impulse to the love of natural history, by surrounding its details with splendid images, and escaping from its rigid investigations by bold and dazzling theories. He rejected classification; and took no pains to distinguish by precise names the objects which he described, because such accuracy would have impeded the progress of his magnificent generalizations. Without classification, and an accurate nomenclature, natural history is a mere chaos. Buffon saw the productions of nature only in masses. He made no endeavour to delineate with perfect accuracy any individual of that immense body, nor to trace the relations of an individual to all the various forms of being by which it is surrounded. Although he was a profound admirer of Newton, and classed Bacon amongst the most illustrious of men, he constantly deviated from the principle of that philosophy upon which all modern discovery has been founded. He carried onward his hypotheses with little calculation and less experiment. And yet, although they are often misapplied, he has collected an astonishing number of facts; and even many of his boldest generalities have been based upon a sufficient foundation of truth, to furnish important assistance to the investigations of more accurate inquirers. The persevering obliquity with which he turns away from the evidence of Design in the creation, to rest upon some vague notions of a self-creative power, both in animate and inanimate existence, is one of the most unpleasant features of his writings. How much higher services might Buffon have rendered to natural history had he been imbued not only with a spirit of accurate and comprehensive classification, but with a perception of the constant agency of a Creator, of both of which merits he had so admirable an example in our own Ray.

The style of Buffon, viewed as an elaborate work of art, and without regard to the great object of style, that of conveying thoughts in the clearest and simplest manner, is captivating from its sustained harmony and occasional grandeur. But it is a style of a past age. Even in his own day, it was a theme for ridicule with those who knew the real force of conciseness and simplicity. Voltaire described it as ‘ empoulé ;’ and when some one talked to him of ‘L’Histoire Naturelle,’ he drily replied, ‘ Pas si naturelle .’ But Buffon was not carried away by the mere love of fine writing. He knew his own power; and, looking at the state of science in his day, he seized upon the instrument which was best calculated to elevate him amongst his contemporaries. The very exaggerations of his style were perhaps necessary to render natural history at once attractive to all descriptions of people. Up to his time it had been a dry and repulsive study. He first clothed it with the picturesque and poetical; threw a moral sentiment around its commonest details; exhibited animals in connection with man, in his mightiest and most useful works; and described the great phenomena of nature with a pomp of language which had never before been called to the service of philosophical investigation. The publication of his works carried the study of natural history out of the closets of the few, to become a source of delight and instruction to all men.

Buffon died at Paris on the 16th April, 1788, aged 81. He was married, in 1762, to Mademoiselle de St. Bélin; and he left an only son, who succeeded to his title. This unfortunate young man perished on the scaffold, in 1795, almost one of the last victims of the fury of the revolution. When he ascended to the guillotine he exclaimed, with great composure, “My name is Buffon.”

A succinct and clear memoir of Buffon, by Cuvier, in the Biographie Universelle, may be advantageously consulted. Nearly all the details of his private life are derived from a curious work by Rénault de Séchelles, entitled Voyage à Montbar, which, like many other domestic histories of eminent men, has the disgrace of being founded upon a violation of the laws of hospitality.

2. Majestati naturæ par ingenium.

3. The best edition of the works of Buffon is the first, of 36 vols. 4to.

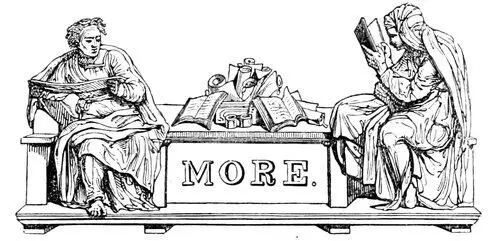

Engraved by R. Woodman. SIR THOMAS MORE. From an Enamel after Holbein, in the possession of Thomas Clarke Esq. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London, Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

This great man was born in London, in the year 1480. His father was Sir John More, one of the Judges of the King’s Bench, a gentleman of established reputation. He was early placed in the family of Cardinal Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor of England. The sons of the gentry were at this time sent into the families of the first nobility and leading statesmen, on an equivocal footing; partly for the finishing of their education, and partly in a menial capacity. The Cardinal said more than once to the nobility who were dining with him, “This boy waiting at table, whosoever lives to see it, will one day prove a marvellous man.” His eminent patron was highly delighted with that vivacity and wit which appeared in his childhood, and did not desert him on the scaffold. Plays were performed in the archiepiscopal household at Christmas. On these occasions young More would play the improvisatore, and introduce an extempore part of his own, more amusing to the spectators than all the rest of the performance. In due time Morton sent him to Oxford, where he heard the lectures of Linacer and Grocyn on the Greek and Latin languages. The epigrams and translations printed in his works evince his skill in both. After a regular course of rhetoric, logic, and philosophy, at Oxford, he removed to London, where he became a law student, first in New Inn, and afterwards in Lincoln’s Inn. He gained considerable reputation by reading public lectures on Saint Augustine, De Civitate Dei, at Saint Lawrence’s church in the Old Jewry. The most learned men in the city of London attended him; among the rest Grocyn, his lecturer in Greek at Oxford, and a writer against the doctrines of Wickliff. The object of More’s prolusions was not so much to discuss points in theology, as to explain the precepts of moral philosophy, and clear up difficulties in history. For more than three years after this he was Law-reader at Furnival’s Inn. He next removed to the Charter-House, where he lived in devotion and prayer; and it is stated that from the age of twenty he wore a hair-shirt next his skin. He remained there about four years, without taking the vows, although he performed all the spiritual exercises of the society, and had a strong inclination to enter the priesthood. But his spiritual adviser, Dr. Colet, Dean of St. Paul’s, recommended him to adopt a different course. On a visit to a gentleman of Essex, by name Colt, he was introduced to his three daughters, and became attached to the second, who was the handsomest of the family. But he bethought him that it would be both a grief and a scandal to the eldest to see her younger sister married before her. He therefore reconsidered his passion, and from motives of pity prevailed with himself to be in love with the elder, or at all events to marry her. Erasmus says that she was young and uneducated, for which her husband liked her the better, as being more capable of conforming to his own model of a wife. He had her instructed in literature, and especially in music.

Читать дальше