His character was marked by undeviating uprightness, industry, and moderation in pursuit of riches. His gains might have been far larger; but he relinquished more than one appointment which brought in a considerable income, to devote his attention to other objects which he had more at heart; and he declined the magnificent offers of Catharine II. of Russia, who would have bought his services at any price. His industry was unwearied, and the distribution of his hours and employments strictly laid down by rule. In his family and by his friends he was singularly beloved, though his demeanour sometimes appeared harsh to strangers. A brief, but very interesting and affectionate account of him, written by his daughter, is prefixed to his Reports, from which many of the anecdotes here related have been derived.

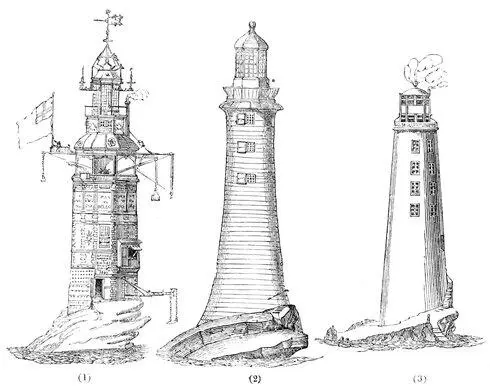

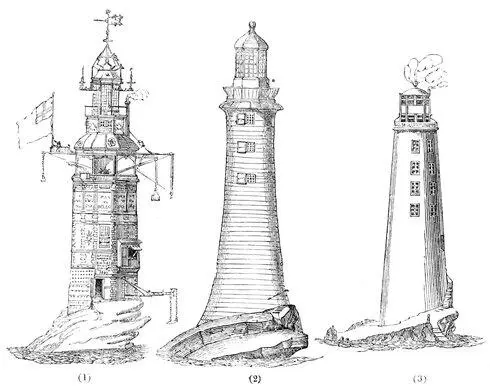

Of the many great undertakings in which Smeaton was engaged, the most original, and the most celebrated, is the Eddystone light-house. The reef of rocks known by the name of the Eddystone lies about nine miles and a half from the Ram Head, at the entrance of Plymouth Sound, exposed to the full swell of the Atlantic, which, with a very moderate gale, breaks upon it with the utmost fury. The situation, directly between the Lizard and Start points, makes it of the utmost importance to have a light-house on it; and in 1698 Mr. Winstanley succeeded in completing one. This stood till 1703, but was entirely carried away in the memorable storm of November 26, in that year. It chanced, by a singular coincidence, that shortly before, on a doubt of the stability of the building being uttered, the architect expressed himself so entirely satisfied on that point, that “he should only wish to be there in the greatest storm that ever blew under the face of the heavens.” He was gratified in his wish; and perished with every person in the building. This building was chiefly, if not wholly of timber. In 1706 Mr. Rudyerd commenced a new light-house, partly of stone and partly of wood, which stood till 1755, when it was burnt down to the very rock. Warned by this accident, Smeaton resolved that his should be entirely of stone. He spent much time in considering the best methods of grafting his work securely on the solid rock, and giving it the form best suited to secure stability; and one of the most interesting parts of his interesting account, is that in which he narrates how he was led to choose the shape which he adopted, by considering the means employed by nature to produce stability in her works. The building is modelled on the trunk of an oak, which spreads out in a sweeping curve near the roots, so as to give breadth and strength to its base, diminishes as it rises, and again swells out as it approaches to the bushy head, to give room for the strong insertion of the principal boughs. The latter is represented by a curved cornice, the effect of which is to throw off the heavy seas, which being suddenly checked fly up, it is said, from fifty to a hundred feet above the very top of the building, and thus to prevent their striking the lantern, even when they seem entirely to enclose it. The efficacy of this construction is such, that after a storm and spring tide of unequalled violence in 1762, in which the greatest fears were entertained at Plymouth for the safety of the light-house, the only article requisite to repair it was a pot of putty, to replace some that had been washed from the lantern.

To prepare a fit base for the reception of the column, the shelving rock was cut into six steps, which were filled up with masonry, firmly dovetailed, and pinned with oaken trenails to the living stone, so that the upper course presented a level circular surface. This part of the work was attended with the greatest difficulty; the rock being accessible only at low water, and in calm weather. The building is faced with the Cornish granite, called in the country, moorstone; a material selected on account of its durability and hardness, which bids defiance to the depredations of marine animals, which have been known to do serious injury by perforating Portland stone when placed under water. The interior is built of Portland stone, which is more easily obtained in large blocks, and is less expensive in the working. It is an instructive lesson, not only to the young engineer, but to all persons, to see the diligence which Smeaton used to ascertain what kind of stone was best fitted for his purposes, and from what materials the firmest and most lasting cement could be obtained. He well knew that in novel and great undertakings no precaution can be deemed superfluous which may contribute to success; and that it is wrong to trust implicitly to common methods, even where experience has shown them to be sufficient in common cases. For the height of twelve feet from the rock the building is solid. Every course of masonry is composed of stones firmly jointed and dovetailed into each other, and secured to the course below by joggles , or solid plugs of stone, which being let into both, effectually resist the lateral pressure of the waves, which tends to push off the upper from the under course. The interior, which is accessible by a moveable ladder, consists of four rooms, one over the other, surmounted by a glass lantern, in which the lights are placed. The height from the lowest point of the foundation to the floor of the lantern is seventy feet; the height of the lantern is twenty-one feet more. The building was commenced August 3, 1756, and finished October 8, 1759; and having braved uninjured the storms of seventy-three winters, is likely long to remain a monument almost as elegant, and far more useful, than the most splendid column ever raised to commemorate imperial victories. Its erection forms an era in the history of light-houses, a subject of great importance to a maritime nation. It came perfect from the mind of the artist; and has left nothing to be added or improved. After such an example no accessible rock can be considered impracticable: and in the more recent erection of a light-house on the dangerous Bell-rock, lying off the coast of Forfarshire, between the Frith of Tay and the Frith of Forth, which is built exactly in the same manner, and almost on the same model, we see the best proof of the value of an impulse, such as was given to this subject by Smeaton.

Light-houses of (1) Winstanley, (2) Smeaton, and (3) Rudyerd.

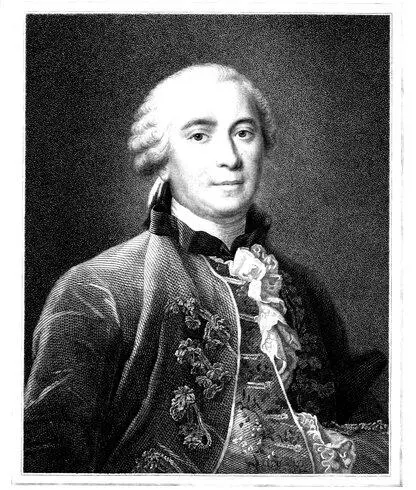

Engraved by Robert Hart. BUFFON. From an original Picture by Drouais in the collection of the Institute of France. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London, Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Buffon is reported to have said—and the vanity which was his predominant foible may have given some colour to the assertion—“I know but five great geniuses, Newton, Bacon, Leibnitz, Montesquieu, and myself.” Probably no author ever received from his contemporaries so many excitements to such an exhibition of presumption and self-consequence. Lewis XV. conferred upon him a title of nobility; the Empress of Russia was his correspondent; Prince Henry of Prussia addressed him in the language of the most exaggerated compliment; and his statue was set up during his life-time in the cabinet of Lewis XVI., with such an inscription as is rarely bestowed even upon the most illustrious of past ages [2]. After the lapse of half a century we may examine the personal character, and the literary merits, of this celebrated man with a more sober judgment.

Читать дальше