It might have been well, however, for the unfortunate Charles if he had been rather more swayed by the opinions of the tutor, and less by the lessons of the pupil. In the early part of Buchanan’s tutorship he attached himself strongly to the interests of the Regent, Murray; and as the patron fell off from the interests of Mary, so did the historian, till at last he became the bitterest of her enemies. He alone has ventured to assert in print his belief of her criminal connexion with David Rizzio, in his ‘Detectio Mariæ Reginæ,’ published in 1571; and he was her great accuser at the court of Elizabeth, when appointed one of the commissioners to inquire into Mary’s conduct, she being a prisoner in England. Buchanan too lies under the serious charge of having forged the controverted letters, supposed to have passed between Mary and her third husband Bothwell, while she was yet the wife of Earl Darnley, from which documents it was made to appear that she was art and part in the murder of her Royal Consort. Whether he really forged these letters or not, is a question perhaps too deeply buried in the dust of antiquity to admit of proof. He offered to swear to their genuineness, however, which was an ill return, if that were all his fault, to the kindness he had received from her. His friendship for Murray continued firm all his life; this man was one of the few persons he seems to have been really attached to. Through the Earl’s interest, Buchanan was made keeper of the Scottish seals, and a Lord of Session. Nothing is told us of his abilities as a practical politician, but it may be supposed that he was fitted for the office he held, for Murray was very careful in the choice of his public servants.

Buchanan’s last work, on which he spent the remaining fourteen years of his life, is yet to be spoken of—his History of Scotland. In this, which like the rest of his productions was written in Latin, he has been said to unite the elegance of Livy with the brevity of Sallust. With this praise, however, and with that which is due to his lively and interesting way of relating a story, our commendations of this work must begin and end. As a history, it is valueless. The early part is a tissue of fable, without dates or authorities, as indeed he had none to give; the latter is the work of an acrimonious and able partisan, not of a calm inquirer and observer of the times in which he lived. The work is divided into four books. The first three contain a long dissertation on the derivation of the name of Britain—a geographical description of Scotland, with some poetical accounts of its ancient manners and customs—a treatise on the ancient inhabitants of Britain, chiefly taken from the traditionary accounts of the bards, and the fables of the monks engrafted on them, on the vestiges of ancient religions, and on the resemblances of the various languages of different parts of the island. The real history of Scotland does not begin till the fourth book; it consists of an account of a regular succession of one hundred and eight kings, from Fergus I. to James VI., a space extending from the beginning of the sixth century to the end of the sixteenth. The apocryphal nature of the greater part of these monarchs is now so fully admitted, that it is unnecessary to dilate upon them. Edward I., as is well known, destroyed all the genuine records of Scottish history which he could find. Buchanan, instead of rejecting the absurd traditionary tales of bards and monks, has merely laboured to dress up a creditable history for the honour of Scotland, and to “clothe with all the beauties and graces of fiction, those legends which formerly had only its wildness and extravagance.”

This work, and his De jure Regni apud Scotos, he published at the same time, very shortly before his death; and, while he was on his death-bed, the Scottish Parliament condemned them both as false and seditious books. We may lay part of this condemnation to James’s account. It is not probable that he would allow so much abuse of his mother as they contained, directly and indirectly, to pass without some public stigma. There remain to be noticed only two small pieces of this author in the Scottish language, one a grievous complaint to the Scottish peers, arising from the assassination of the Earl of Murray; the other, a severe satire against Secretary Maitland, for the readiness with which he changed from party to party: this has the title of ‘Chameleon.’

Buchanan died at the good old age of seventy-four, in his dotage as his enemies said, but in full vigour of mind as his last great work, his History, has proved. Much has been said in his dispraise by enemies of every class, his chief detractors being the partisans of Mary Stuart and the Romish priesthood. The first of these accuse him of ingratitude to Major, Mary, Morton, Maitland, and to others of his benefactors; of forging the letters above-mentioned, and of perjury in offering to swear to them. The latter accuse him of licentiousness, of drunkenness, and falsehood; and one of them has descended so far as to quarrel with his personal ugliness. Of these charges many are, to say the least, unproved; many appear to be altogether untrue. But his fame rests rather on his persevering industry, his excellent scholarship, and his fine genius, than upon his moral qualities. Buchanan wrote his own life in Latin two years before his death. To this work, to Mackenzie’s ‘Lives and Characters of the most eminent writers of the Scots Nation,’ to the Biographia Britannica, and the numerous authorities on insulated points there quoted, we may refer those who wish to pursue this subject. Buchanan’s works were collected and edited by the grammarian Ruddiman, and printed by Freebairn, at Edinburgh, in the year 1715, in two volumes, folio.

2. See his epigram. “In Johannem solo cognomento Majorem ut ipse in fionte libri scripsit.”

Cum scateat nugis solo cognomine Major,

Nec sit in immenso patina sana libro;

Non minem titulis quod se veracibus ornet;

Nec semper mendax fingere Creta solet.

The book was “ane most fulish tractate on ane most emptie subject.”

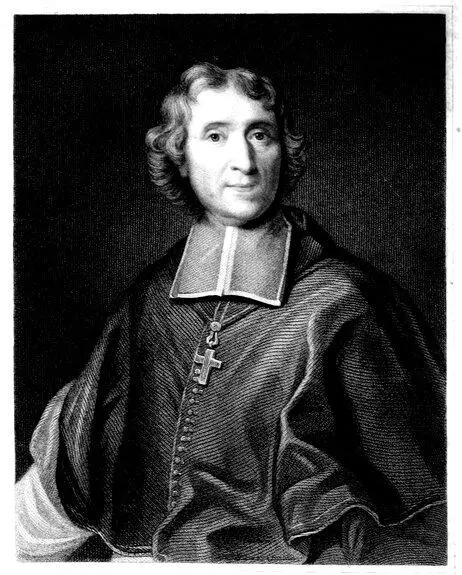

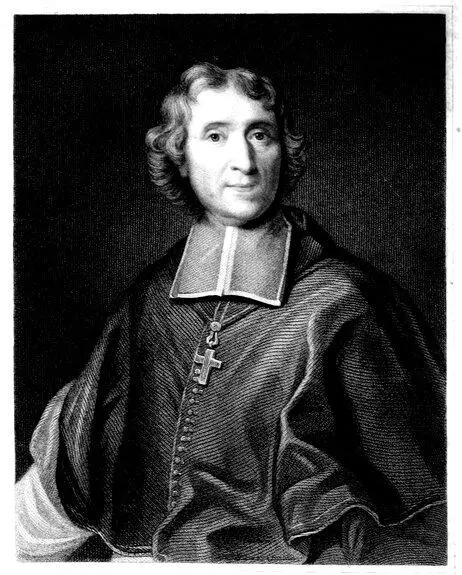

Engraved by J. Thomson. FÉNÉLON. From the original Picture by Vivien in the Collection at the Louvre. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Francois de Salignac de Lamothe-Fenelon was born August 6th, 1651, at the Castle of Fenelon, of a noble and ancient family in the province of Perigord.

Early proofs of talent and genius induced his uncle, the Marquis de Fenelon, a man of no ordinary merit, to take him under his immediate care and superintendence. By him he was placed at the seminary of St. Sulpice, then lately founded in Paris for the purpose of educating young men for the church.

The studies of the young Abbé were not encouraged by visions of a stall and a mitre. It seems that the object of his earliest ambition was, as a missionary, to carry the blessings of the Gospel to the savages of North America, or to the Mahometans and heretics of Greece and Anatolia. The fears, however, or the hopes of his friends detained him at home, and after his ordination he confined himself for several years to the duties of the ministry in the parish of St. Sulpice.

Читать дальше