This ebullition of popular favour encouraged Lorenzo to complete the consolidation of his power by fresh encroachments on the rights of his countrymen. In 1481 another plot was formed against him; but his watchful agents discovered it, and Battista Frescobaldi, with two of his accomplices, were hanged. Tranquil and secure at home, as well as peaceful and respected abroad, he now diverted his mind from public business to literary leisure, and spent his time in the society of men of talent, in philosophical studies, and in poetical composition. But his rational enjoyments had a short duration. Early in 1492 he was attacked by a slow fever, which, combined with his hereditary complaints, warned him of his approaching end. Having sent to request the attendance of the famous Savonarola, to whom he was desirous of making his confession, the austere Dominican readily complied with his wish, but declared he could not absolve him unless he restored to his fellow-citizens the rights of which he had despoiled them. To such a reparation Lorenzo would not consent; and he died without obtaining the absolution he had invoked. Piero, the eldest of his three sons, was deprived of the sovereignty in consequence of the reaction that the eloquent sermons of Savonarola produced in the morals of Florence. Giovanni, whom Innocent VIII., by a prostitution of ecclesiastical honours unprecedented in the annals of the church, had raised to the Cardinalship at the early age of thirteen, became Pope under the name of Leo X., and gave rise to the Reformation by his extreme profligacy and extravagance; and Giuliano, who afterwards allied himself by marriage to the royal House of France, was elevated to the dignity of Duke of Nemours.

Lorenzo de Medici has been extolled with immoderate applause as a poet, a patron of learning, and a statesman. His voluminous poetical compositions, embracing subjects of love, rural life, philosophy, religious enthusiasm, and coarse licentiousness, exhibit an uncommon versatility of genius, a rich imagination, and a remarkable purity of language; but in spite of the exaggerated eulogies lavished on them by his own flatterers and by those of his dependants, they never obtained any popularity, and are now nearly buried in oblivion. His efforts for the diffusion of knowledge and taste shine more conspicuous; in this laudable course he followed the traces of Cosmo and of his father. It is, however, impossible to conceive any strong reverence or respect for his memory without forgetting his political conduct, which is far from deserving any praise.

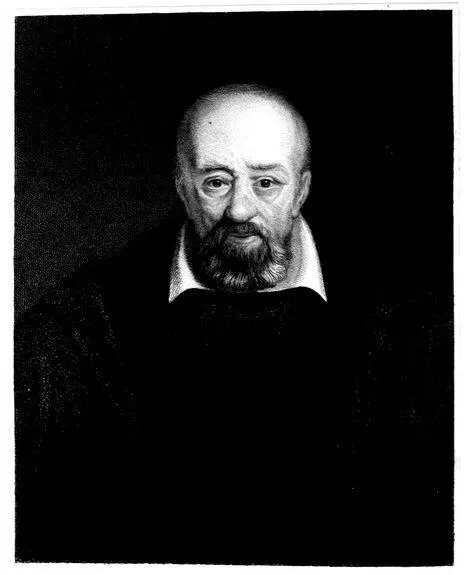

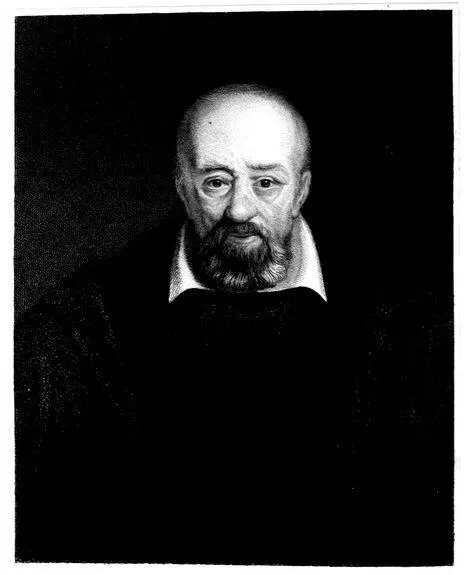

Engraved by E. Scriven. GEORGE BUCHANAN. From a Picture by Francis Pourbus Sen. in the possession of the Royal Society. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

George Buchanan was born in February, 1506, at a small village called Killearn, on the borders of Stirlingshire and Dumbartonshire. He came, as he says, “of a family more gentle and ancient than wealthy.” His father dying, left a wife and eight children in a state of poverty. George, one of the youngest, was befriended, and, perhaps, saved from want and obscurity, by the kindness of his mother’s brother, James Heriot, who had early remarked his nephew’s talents, and determined to foster them by a good education. The ancient friendship between France and Scotland, cemented by their mutual hate of England, was then in full force. The Scotch respected the superiority of the French in manners, arts, and learning; and very commonly sent the wealthier and more promising of their youth to be educated by their more polished neighbours. Accordingly Buchanan, at the age of fourteen, was sent by his uncle to the University of Paris. Here he applied himself most diligently to the prescribed course of study, which consisted principally in a careful perusal of the best Latin authors, especially the poets. This kind of learning was peculiarly suited to his taste and genius; and he made such progress, as not only to become a sound scholar, but one of the most graceful Latin writers of modern times.

After having remained in Paris for the space of two years, which he must have employed to much better purpose than most youths of his age, the death of his kind uncle reduced him again to poverty. Partly on this account, partly from ill health, he returned to his own country, and spent a year at home. Alter having recruited his strength, he entered as a common soldier into a body of troops that was brought over from France by John Duke of Albany, then Regent of Scotland, for the purpose of opposing the English. Buchanan himself says that he went into the army “to learn the art of war;” it is probable that his needy circumstances were of more weight than this reason. During this campaign he was subjected to great hardships from severe falls of snow; in consequence of which he relapsed into his former illness; and was obliged to return home a second time, where he was confined to his bed a great part of the winter. But on his recovery, in the spring of 1524, when he was just entering upon his 18th year, he again took to his studies, and pursued them with great ardour. He seems to have found friends at this time rich enough to send him to the University of St. Andrews, on which foundation he was entered as a pauper , a term which corresponds to the servitor and sizer of the English Universities. John Mair, better known (through Buchanan [2]) by his Latinized name of Major, was then reading lectures at St. Andrews on grammar and logic. He soon heard of the superior accomplishments of the poor student, and immediately took him under his protection. Buchanan, notwithstanding his avowed contempt for his old tutor, must have imbibed from Major many of his opinions. He was of an ardent temper, and easy, as his contemporaries tell us, to lead whichever way his friends desired him to go; he was also of an inquiring disposition, and never could endure absurdities of any kind. This sort of mind must have found great delight in the doctrines which Major taught. He affirmed the superiority of general councils over the papacy, even to the depriving a Pope of his spiritual authority in case of misdemeanour; he denied the lawfulness of the Pope’s temporal sway; he held that tithes were an institution of mere human appointment, which might be dropped or changed at the pleasure of the people; he railed bitterly against the immoralities and abominations of the Romish priesthood. In political matters his creed coincides exactly with Buchanan’s published opinions—that the authority of kings was not of divine right, but was solely through the people, for the people; that by a lawful convention of states, any king, in case of tyranny or misgovernment, might be controlled, divested of his power, or capitally executed according to circumstances. But if Major, who was a weak man and a bad arguer, had such weight with Buchanan, John Knox, the celebrated Scottish reformer, who was a fellow-student with him at St. Andrews, must have had still more. They began a strict friendship at this place, which only ended with their lives. Knox speaks very highly of him at a late period of his own life: “That notabil man, Mr. George Bucquhanane, remainis alyve to this day, in the yeir of God 1566 yeares, to the glory of God, to the gret honor of this natioun, and to the comfort of thame that delyte in letters and vertew. That singular work of David’s Psalmes, in Latin meetere and poesie, besyd many uther, can witness the rare graices of God gevin to that man.” These two men speedily discovered the absurdity of the art of logic, as it was then taught. Buchanan tells us that its proper name was the art of sophistry. Their mutual longings for better reasonings, and better thoughts to reason upon, produced great effects in the reformation of their native country.

Читать дальше