Table of Contents

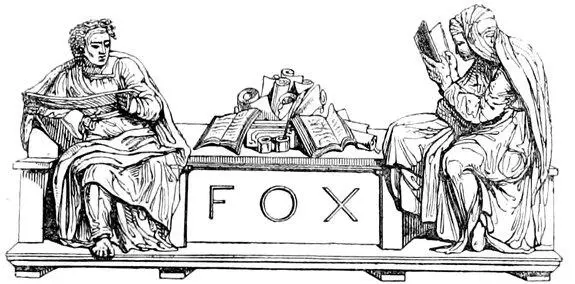

The Right Honourable Charles James Fox was third son of the Right Honourable Henry Fox, afterwards Lord Holland, and of Lady Georgina Caroline Fox, eldest daughter of Charles, second Duke of Richmond. He was born January 24th, 1749, N. S.

Mr. Fox received his education at Eton; and the favourite studies of the place had more than ordinary influence over his tastes and literary pursuits in after-life. Before he left school, his father was so imprudent as to carry him to Paris and Spa. To his early associations at the latter place may be ascribed that propensity to gaming, which was the bane of two-thirds of his life. As the present article is not designed to be a mere panegyric, we abandon the indulgence of this fatal passion to the severest censure that can be bestowed upon it by the philosopher and the moralist: but justice demands it at our hands to say, that after the adjustment of Mr. Fox’s affairs by his friends, personal and political, he resolutely conquered what habit had almost raised into second nature, and abstained from play with scrupulous fidelity. It may further be remarked, that while the paroxysms of the fever were most violent, his mind was never interrupted from more worthy objects of pursuit.

The following anecdote will show the divided empire which discordant passions alternately usurped over his heart. On a night when he had sustained some serious losses, his deportment assumed so much of the character of despair, that his friends became uneasy: they followed him at distance enough to elude his observation, from the clubhouse to his home in the neighbourhood. They knocked at his door in time, as they thought, to have prevented any rash act, and rushed into the library. There they found the object of their anxiety stretched on the ground without his coat, before the fire: his hand neither grasping a razor nor a pistol, but his eyes intently fixed on the pages of Herodotus. The old historian had engrossed him wholly from the moment when he took up the volume, and the ruins of his own air-built castles vanished from before him, as soon as he got sight of the venerable remains of the ancient world.

At Oxford Mr. Fox distinguished himself by his powers of application, as well as by the intuitive quickness of his parts. On quitting the university, he accompanied his father and mother to the south of Europe. Not finding a good Italian master at Naples, he taught himself that language during the winter, and contracted a strong partiality for Italian literature. In a letter from Florence to Mr. Fitz-Patrick, he conjures that gentleman to learn Italian as fast as he can, if it were only to read Ariosto; and adds, “There is more good poetry in Italian than in all other languages I understand put together.” At a later period of life, if we may judge from the tenor of his correspondence with eminent scholars, he would have transferred that praise from the Italian to the Greek tongue. At this time he was very fond of acting plays, and was in all respects the man of fashion. Those who recollect the simplicity, bordering on negligence, of his outward garb late in life, will smile at the idea of Mr. Fox with a powdered toupee and red heels to his shoes, the hero of private theatricals. During his absence, in 1768, he was chosen to represent Midhurst, and made his first speech on the 15th April, 1769. According to Horace Walpole, he spoke with violence, but with infinite superiority of parts.

Circumscribed as we are as to space, we shall not follow Mr. Fox’s subaltern career in the House of Commons. It was his breach with Lord North that raised him into a party leader. He had previously formed an intimate acquaintance with Mr. Burke. He began by receiving the lessons of that eminent person as a pupil; but the master was soon so convinced of his scholar’s greatness of character, and statesman-like turn of mind, that he resigned the lead to him, and became an efficient coadjutor in the Rockingham party, of which, in the House of Commons, he had almost been the dictator. The American war roused all the energies of Mr. Fox’s mind. The discussions to which it gave rise involved all the first principles of free government. The vicissitudes of the contest tried the firmness of the parliamentary opposition. Its duration exercised their perseverance. Its magnitude and the dangers of the country called forth their powers. Gibbon says, “Mr. Fox discovered powers for regular debate, which neither his friends hoped nor his enemies dreaded.” The following passage, from a letter to Mr. Fitz-Patrick, written in 1778, illustrates his honourable and independent character: “People flatter me that I continue to gain rather than lose estimation as an orator; and I am so convinced this is all I ever shall gain (unless I choose to be one of the meanest of men), that I never think of any other object of ambition. I am certainly ambitious by nature, but I have, or think I have, totally subdued that passion. I have still as much vanity as ever, which is a happier passion by far, because great reputation, I think, I may acquire and keep; great situations I never can acquire, nor, if acquired, keep, without making sacrifices that I will never make.” In the summer of 1778, he rejected Lord Weymouth’s overtures to join the ministry, and took his station as the leading commoner in the Rockingham party, to which he had become attached on principle long before he enlisted permanently in its ranks. The conspicuous features of that party, and of Mr. Fox’s public character, were the love of peace with foreign powers, the spirit of conciliation in home management, an ardent attachment to civil and religious liberty.

The day of triumph came at last, when a resolution against the further prosecution of the American war was carried in the Commons. The King was compelled, reluctantly, to part with the supporters of his favourite principles, and had nothing left but to sow the seeds of disunion between the Rockingham and Chatham or Shelburne party, united on the subject of America, but disagreeing on many other points both of external and internal policy. In this he was but too successful. We have neither space nor inclination to unravel the web of court intrigue; but we may remark that Lord Rockingham’s demands were too extensive to be palatable: they involved the independence of America, the pacification of Ireland, bills for economical and parliamentary reform, to be brought into Parliament as ministerial measures. But the untimely death of Lord Rockingham frustrated his enlightened and enlarged designs, by dissolving the ministry over which he had presided. Mr. Fox has been blamed for the precipitancy of his resignation. The tone of sentiment in a letter before quoted will both account and apologise for the rashness if it were such; and it is obvious that the sacrifice of personal feeling, or even of political consistency, could not long have deferred it, amidst the cabals and clashing interests of party. Mr. Fox’s policy was to detach Holland and America from France, and to form a continental balance against the House of Bourbon. Lord Shelburne’s system was to conciliate France, and to treat her allies as dependent powers. Lord Shelburne had the ear of the King. He strengthened himself with some of the old supporters of the American war, to fill the vacant offices, and made Mr. Pitt, just rising into eminence, his Chancellor of the Exchequer. There were now three parties in the Commons; the ministerial, the Whig or Rockingham, and the third consisting of those members of the late war ministry who had not been invited to join the present. A coalition of some two of these three parties was almost unavoidable: the public would have most approved of a reunion among the Whigs; but there had been too much of mutual recrimination and dispute to admit of reconciliation. Nothing, therefore, remained but a junction of the two parties in opposition. A judicious friend of Mr. Fox said, “that to undertake the government with Lord North, was to risk their credit on very unsafe grounds. Unless a real good government is the consequence of this junction, nothing can justify it to the public.” Popular feeling was strongly against this coalition, mainly on account of some personal acrimony vented by Mr. Fox, in the boiling over of his wrath during the American contest, which seemed to bear upon the moral character of his opponent. It is to be considered, however, that the most amiable persons, if enthusiastic, are apt in the heat of passion to launch out into invective far more violent than their natural benevolence would justify in their cooler moments. The question on which Mr. Fox and Lord North had been so acrimoniously opposed, had ceased to exist: and perhaps there existed no solid reason against the union of the two parties. But the measure was almost universally believed to arise from corrupt motives: it afforded a fine scope for satire and caricature; and these have no small influence upon the politics of the multitude. And while the people were displeased, the King was decidedly unfriendly to the administration which had forced itself upon him. He considered the Rockingham party as enemies to his prerogative, as well as friends to American independence. He was forced to take them in, but resolved to throw them out again. The unpopular India bill, which Mr. Pitt afterwards adopted with some modifications, furnished the opportunity. The offence taken by the people against the coalition, made them lend a ready ear to the charge of ministerial oligarchy: the King disguised his sentiments till the last moment, procured the rejection of the bill in the Lords, and instantly dismissed his ministers.

Читать дальше