His earlier architectural works are to be seen at Florence. They consist of the façade and sacristy of the church of St. Lorenzo, left unfinished by Brunelleschi, the mausoleum of the Medici family, and the Laurentian library. During the latter part of his life he amused his leisure hours by working on a group representing a dead Christ, supported by the Virgin and Nicodemus, which he intended for an altar-piece to the chapel in which he should himself be interred. It was never finished, however, and is now in the cathedral of Florence. But, from the time of his assuming the charge of St. Peter’s, his attention was almost entirely devoted to architecture. His chief works were the completion of the Farnese palace, begun by San Gallo; the palace of the Senator of Rome, the picture galleries, and flight of steps leading up to the convent of Araceli, all situated on the Capitoline hill; and the conversion of the baths of Diocletian into the church of S. Maria degli Angeli.

Michael Angelo, though he painted few pictures himself, frequently gave designs to be executed by his favourite pupils, especially Sebastiano del Piombo. Such was the origin of the magnificent Raising of Lazarus, in the National Gallery. Like many artists of that age, he aspired to be a poet. His works consist chiefly of sonnets, modelled on the style of Petrarch. Religion and Love are the prevailing subjects.

The Life of Michael Angelo, by Mr. Duppa, will gratify the curiosity of the English reader, who wishes to pursue the subject beyond this mere list of the artist’s principal works. To the Italian reader we may recommend the lives of Condivi and Vasari, as containing the original information from which subsequent writers have drawn their accounts. To do justice to the versatile, yet profound genius of this great man, is a task which we must leave to such writers as Reynolds and Fuseli, in whose lectures the reader will find ample evidence of the profound admiration with which they regarded him. Nor can we conclude better than with the short but energetic character given by the latter, of his favourite artist’s style of genius, and of his principal works:—

“Sublimity of conception, grandeur of form, and breadth of manner, are the elements of Michael Angelo’s style. By these principles he selected or rejected the objects of imitation. As painter, as sculptor, as architect, he attempted, and above any other man, succeeded, to unite magnificence of plan, and endless variety of subordinate parts, with the utmost simplicity and breadth. His line is uniformly grand: character and beauty were admitted only as far as they could be made subservient to grandeur. To give the appearance of perfect ease to the most perplexing difficulty, was the exclusive power of Michael Angelo. He is the inventor of epic painting, in that sublime circle of the Sistine chapel which exhibits the origin, the progress, and the final dispensations of theocracy. He has personified motion in the groups of the Cartoon of Pisa; embodied sentiment on the monuments of S. Lorenzo; unravelled the features of meditation in the Prophets and Sibyls of the Sistine chapel; and in the Last Judgment, with every attitude that varies the human body, traced the master-trait of every passion that sways the human heart. Though, as sculptor, he expressed the character of flesh more perfectly than all who came before or went after him, yet he never submitted to copy an individual, Julius II. only excepted; and in him he represented the reigning passion rather than the man. In painting he has contented himself with a negative colour, and as the painter of mankind, rejected all meretricious ornament. The fabric of St. Peter’s, scattered into infinity of jarring parts by Bramante and his successors, he concentrated; suspended the cupola, and to the most complex gave the air of the most simple of edifices. Such, take him for all in all, was M. Angelo, the salt of art: sometimes he no doubt had his moments of dereliction, deviated into manner, or perplexed the grandeur of his forms with futile and ostentatious anatomy: both met with armies of copyists; and it has been his fate to be censured for their folly.”—(Lecture II.)

JACKSON

From the Monument of Giuliano de Medici.

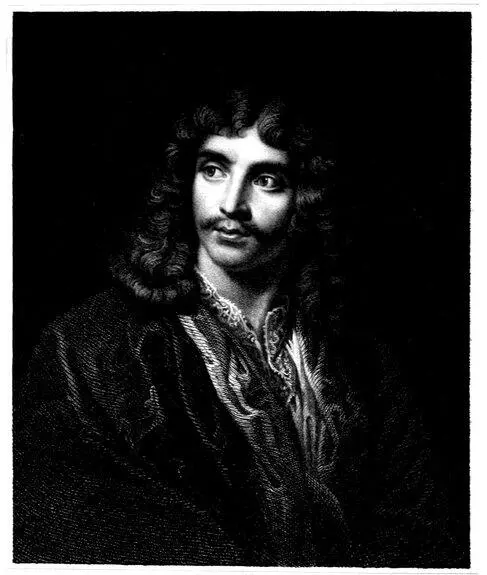

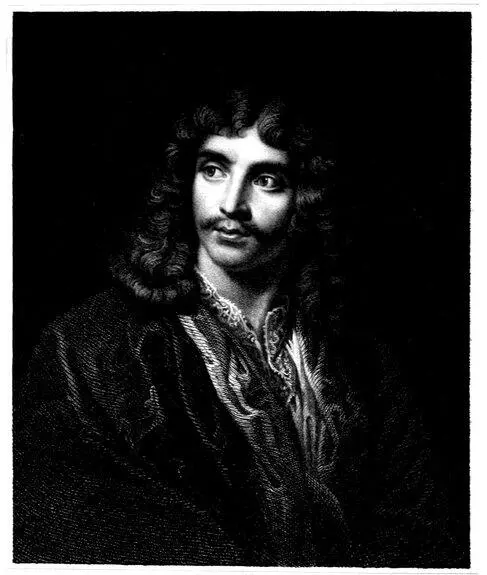

Engraved by J. Posselwhite. MOLIERE. From the original Picture of Lebrun’s School, in the collection of the Musée Royale. Paris. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Moliere, the contemporary of Corneille and Racine, whose original and real name was Jean Baptiste Poquelin, was born at Paris on the 15th January, 1622. His father and mother were both in trade; and they brought up their son to their own occupation. At the age of fourteen, young Poquelin could neither read, write, nor cast accounts. But the grandfather was very fond of him; and being himself a great lover of plays, often took his favourite to the theatre. The natural genius of the boy was, by this initiation, kindled into a decided taste for dramatic entertainments: a disgust to trade was the consequence, and a desire of that mental cultivation from which he had hitherto been debarred. His father consented at length to his becoming a pupil of the Jesuits at the College of Clermont. He remained there five years, and was fortunate enough to be the class-fellow of Armand de Bourbon, Prince de Conti, whose friendship and protection proved of signal service to him in after-life. He studied under the celebrated Gassendi, who was so impressed by the apparent aptitude of young Poquelin to receive instruction, that he admitted him to the private lectures given to his other pupils. Gassendi was in the habit of breaking a lance with two great rivals: Aristotle, at the head of ancient, and Descartes, then at the head of modern philosophy. By witnessing this combat, Poquelin acquired a habit of independent reasoning, sound principles, extensive knowledge, and that feeling of practical good sense, which was so conspicuous not only in his most laboured, but even in his lightest productions.

His studies under Gassendi were abruptly terminated by the following circumstance. His father was attached to the court in the double capacity of valet-de-chambre and tapestry-maker; and the son had the reversion of these places. When Louis XIII. went to Narbonne in 1641, the old man was ill, and the young one was obliged to officiate for him. On his return to Paris, his passion for the stage, which had first led him into the paths of literature, revived with renewed strength. The taste of Cardinal de Richelieu for theatrical performances was communicated to the nation at large, and a peculiar protection was granted to dramatic poets. Many little societies were formed for acting plays in private houses, for the amusement at least of the performers. Poquelin collected a company of young stage-stricken heroes, who so far exceeded all their rivals, as to earn for their establishment the pompous title of The Illustrious Theatre. He now determined to make the stage his profession, and changing his name, according to the usage in such cases, adopted that of Moliere.

He disappears during the time of the civil wars, from 1648 to 1652; but we may suppose the interval to have been passed in composing some of those pieces which were afterwards brought before the public. When the disturbances ceased, Moliere, in partnership with an actress of Champagne, named La Béjard, formed a strolling company; and his first regular piece, called L’Etourdi, or the Blunderer, was performed at Lyons in 1653. Another company of comedians settled in that town was deserted by the spectators in favour of these clever vagabonds; and the principal performers of the regular establishment took the hint, pocketed their dignity, and joined Moliere. The united company transferred itself to Languedoc, and were retained in the service of the Prince of Conti. During the Carnival of 1658, the troop, having resumed their vagrant life, were playing at Grenoble. The following summer was passed at Rouen. When so near Paris, Moliere made occasional journeys thither, with the earnest hope of bettering his fortune in the metropolis, where the market for talent is always brisk and open, the competition, though severe, fair and encouraging. Once more he received protection from his august fellow-collegian, who introduced him to Monsieur, and ultimately to the King himself. The company appeared before their Majesties and the court for the first time, on the 3d of November, 1658, on a stage erected in the Hall of the Guards in the Old Louvre. Their success was so complete that the King gave orders for their permanent settlement in Paris, and they were allowed to act alternately with the Italian players in the Hall of the Petit Bourbon. In 1663 a pension of a thousand livres was granted to Moliere, and in 1665 his company was taken altogether into the King’s service.

Читать дальше