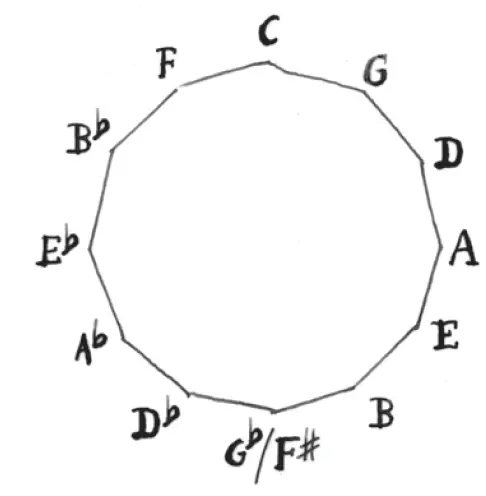

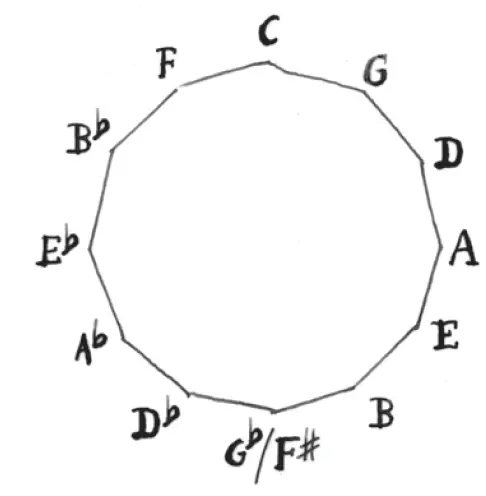

He turned his back to the class and drew the circle of fifths on the blackboard:

There you could see it. It began with C and ended with C, only seven octaves higher. It was simple.

‘And where is the Pythagorean Comma?’ enquired the teacher.

‘Yes,’ Bach said, ‘that’s the real problem. If you tune perfect octaves, namely from C to C’ and so forth, you’ll have a different note than by tuning to perfect fifths.’

‘Why?’ the teacher asked. ‘Why is that?’

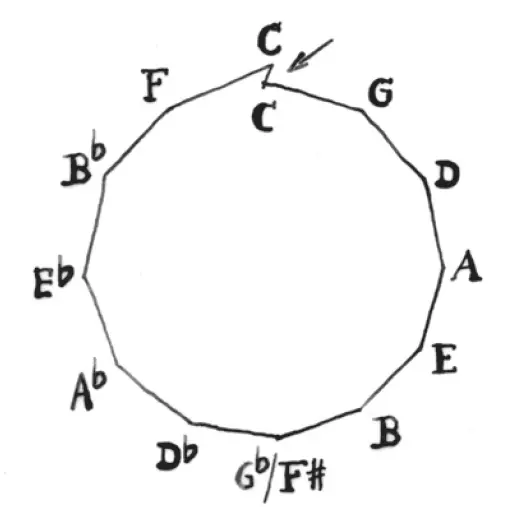

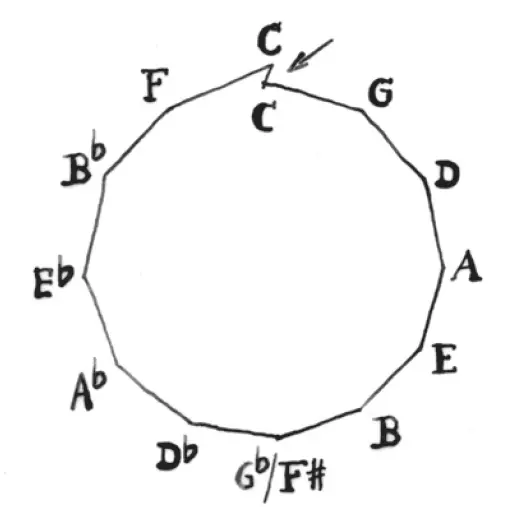

‘Well,’ said Bach. ‘It’s a problem that hitherto no science has been able to resolve. The fact is, twelve perfect fifths result in a different note than seven perfectly tuned octaves.’ Bach turned to the blackboard again, wiping away a section of the chalk circle at the upper C and added a small spike. Then he drew an arrow pointing straight to the spike and said: ‘There. Here you can see it. The circle of fifths doesn’t close. The beginning and the end do not match. God has presented us with a riddle here.’

‘Thank you, Bach,’ said the teacher, ‘that was an excellent lecture.’

Bach put down the piece of chalk and strode back to his place.

‘But,’ queried an apothecary’s son after the teacher had allowed him to speak, ‘what does all this actually mean?’

‘What it means ,’ said Bach, ‘is that you cannot play in all keys on the organ or the clavichord. If the instrument has been tuned in C, you can get barely to E major, and after that the wolf howls.

The howling of the wolf was an expression musicians used to describe a fifth that was so far out of tune that it only sounded miserable. It was called the wolf fifth .

‘All right,’ said the apothecary’s son, ‘but what does it all signify?’

‘It primarily signifies,’ Erdmann interjected, in the arrogant tone he had learned from listening to the aristocratic students, ‘that the order of the world is highly imperfect.’

‘Imperfect?’ asked the teacher, crossing his arms.

‘Well,’ said Erdmann, rising from his seat, ‘after all, the world is indeed anything but perfect! At least it’s in dire need of improvement – all progressive scholars are agreed on that.’

‘So God has created the world in an imperfect manner?’ enquired the teacher. ‘That’s how His Lordship meant it – right, Erdmann? So God created the world – well, what now, Erdmann? Give me a hand here. Did He do so sloppily? In a slipshod manner?’

‘Well …’

Bach saw beads of perspiration on Erdmann’s upper lip.

‘But we just heard it from Bach,’ Erdmann said hesitantly. ‘Everything doesn’t fit together quite right here. It’s not as it ought to be. If you tune to perfect octaves, you get to a different note than you do when with tuning to perfect fifths. Such a difference would not exist in a perfect world. In a perfect world, the circle of fifths would be closed.’

He folded his arms across his chest now, so they stood facing each other, the teacher and the student, both with crossed arms.

‘So Your Highness intends to improve upon God’s creation?’ the teacher said ironically, unfolding his arms. ‘It’s not good enough for His Lordship: His Lordship knows better, and His Lordship will show us. His Lordship will show GOD, am I right? Answer me!’

Bach would have liked to help Erdmann, but how? Erdmann was his friend. He admired his courage. He admired his brilliance. But was it permitted to set oneself up as a judge of Creation?

All the colour had drained from Erdmann’s face. Beads of cold sweat covered his forehead.

‘Just at the moment, I can’t answer that,’ said Erdmann evasively. ‘I have to think it over first.’

‘Well,’ the teacher said, smiling, ‘get on with it, Erdmann. So now His Lordship has three days to think over how he wants to improve God’s work. Three days in detention – get out!’

Upright, with hunched shoulders, striding stiffly, his eyes fixed in front of him, Erdmann stalked to the door and set out for the detention room.

The thing Bach missed most of all was playing the organ. The organ of the St Michael’s Church was in miserable condition. What good does it do to have thirty-two registers if only twenty-five of them work? There was another, smaller organ, but it was badly out of tune. It hurt his ears to listen to it during service, especially when he stood in for the organist, which was frequently the case. If the classroom and choir practice left him enough time for it, he made a pilgrimage to the other end of the town, where, at St John’s Church on Market Square, the great Georg Böhm played the organ. He had never heard a master like him. In terms of virtuosity and expressiveness, Böhm outmatched even Uncle Christoph in Eisenach.

For days and weeks, Bach had only dreamed of being a pupil of this master organist but, since he adored him so much, he could not bring himself to ask. Once, after Böhm had played his last chord, Bach walked up to him, his heart pounding in his throat, determined to speak to him; but when the pastor came and spoke a few words with the organist, his courage abandoned him once more. With a flushed face, he crept out of the church, crossed the Market Square and fled through Sandviertel back to the school.

Instead of going to Böhm, he went to see the Lion: Johann Jacob Löwe – self-styled ‘Lion of Eisenach’ – played the organ at St Nicholas’s. Bach waited for him after the service and watched him descend, rather uncertainly, from the gallery, supported by the bellows treader, who preceded him down the steep stairs. He wore a black jacket, black trousers and had a shaggy wig on his head. His ancient features appeared as though carved from wood; the eyes were colourless, covered by a milky mist. Was he blind?

‘What’s the matter?’ he asked after the bellows treader had said goodbye.

‘The low A,’ Bach said, and was immediately angry with himself. He had wanted to say anything but that.

‘I know, I know,’ the Lion growled. ‘The E isn’t faring much better. And the G is also too low.’

‘And the F in the third octave,’ Bach added.

‘Can’t do anything about it,’ the Lion said.

‘Maybe a little sand could fill up the pipes,’ Bach suggested in a respectful tone. ‘With due care and attention, of course.’

‘No,’ said the Lion. ‘That would mess up the entire structure. It’s better that everything is a little off than having some absolutely pure notes. They would just be all the more conspicuous. So, if that was all, then God be with you.’

Bach was silent, but stood his ground.

‘What else?’ the Lion asked with a hint of curiosity. ‘Out with it! I must go, my meal’s waiting. The housekeeper will tear my head off if I’m late.’

‘Most humbly, I ask …’

‘Well?’

‘… for lessons.’

‘With whom?’

‘With the Lion of Eisenach.’

‘With me? Why?’

Because I didn’t have the courage to ask Böhm .

‘Because I have the desire to perfect my playing,’ he said aloud and added: ‘For the glory of God.’

The Lion looked at him searchingly. ‘No longer giving lessons,’ he finally said. ‘Too old. Can’t stand any more of this bungling.’

‘I’m not a bungler,’ said Bach. ‘I could prove it if the bellows treader were still here.’

Читать дальше