Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781119754381 (Cloth)

ISBN 9780857088956 (epdf)

ISBN 9780857088932 (epub)

Cover design: Wiley

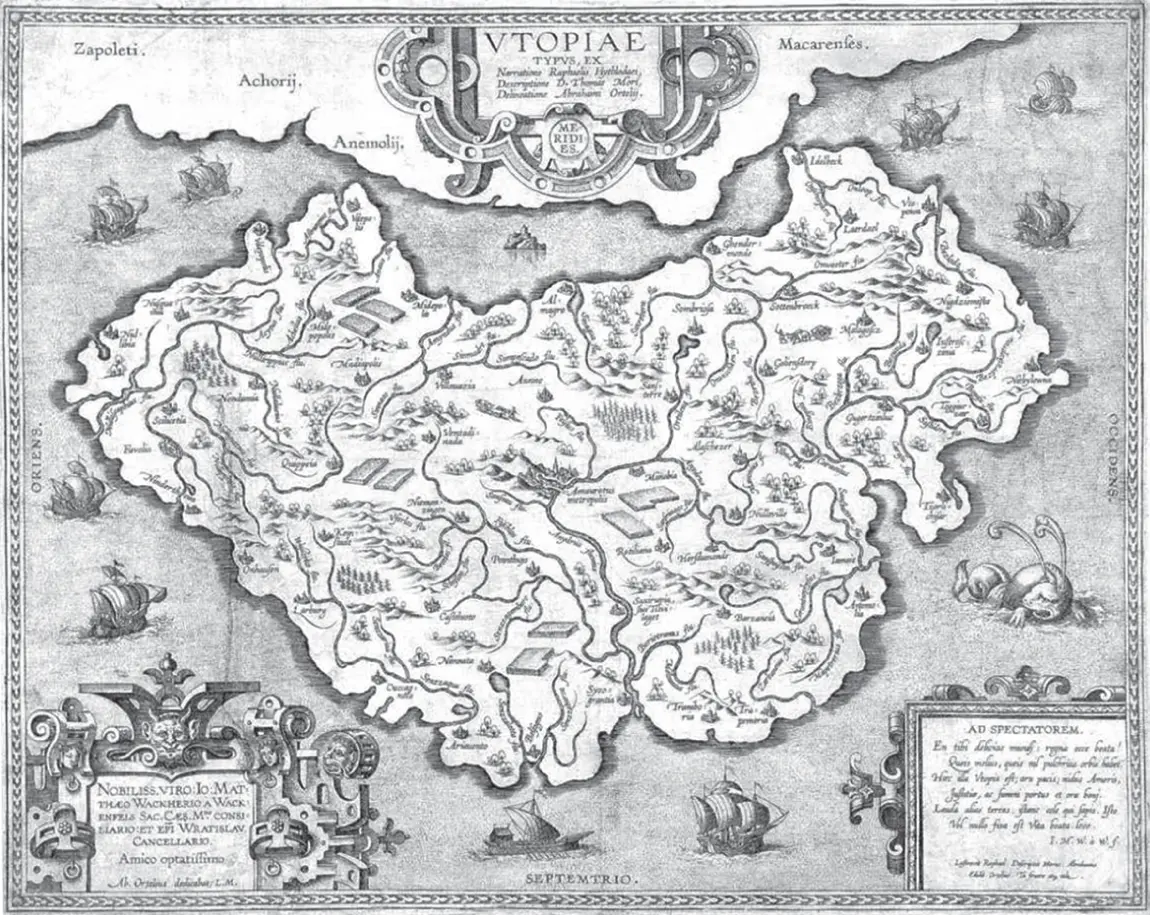

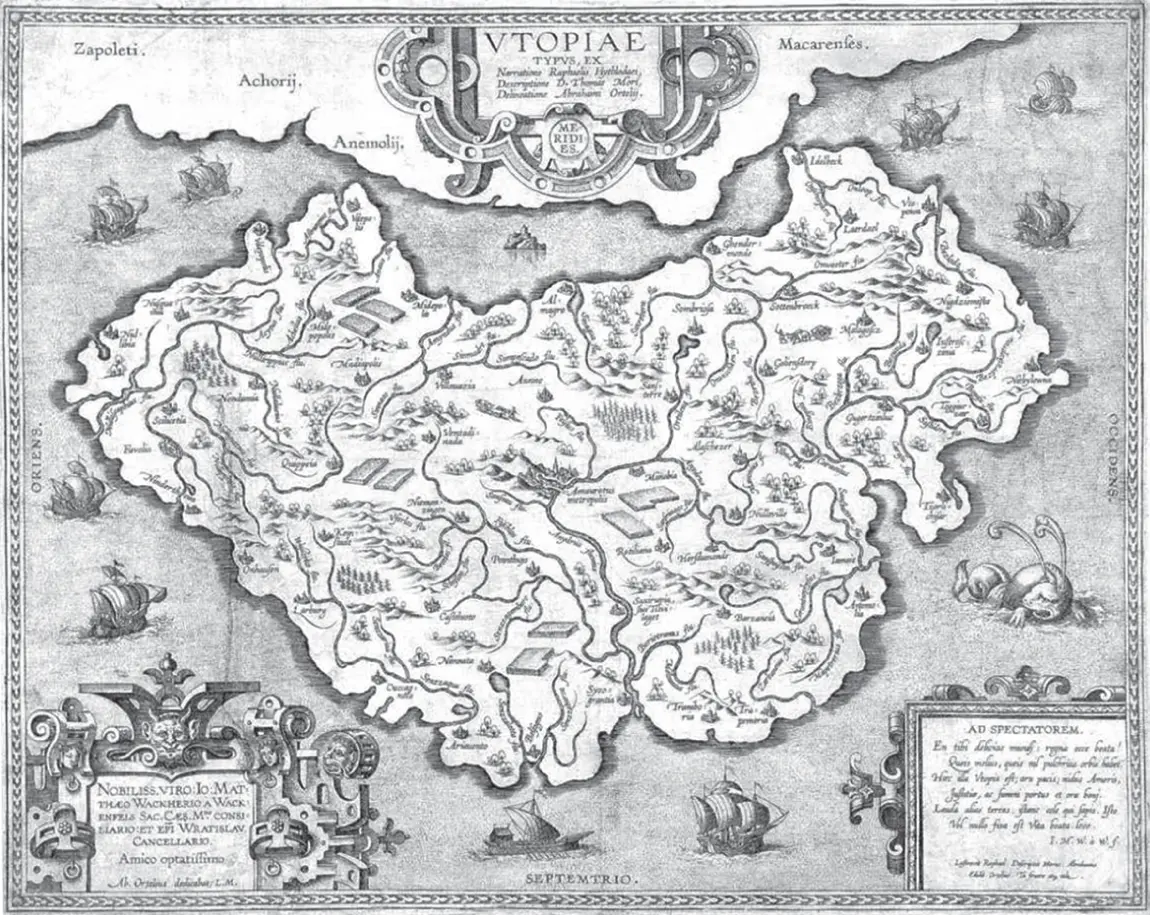

Map of Utopia by Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) circa 1595

BY NIALL KISHTAINY

In 1516, a book written in Latin was published with the invented word ‘utopia’ in its title: Concerning the Best State of a Commonwealth, and the New Island of Utopia . It described an imaginary place, a good society located somewhere in the New World. The book contained a map of a distant island and a translation of a curious alphabet purportedly used by the islanders. Utopia , as the book became known, was Thomas More's most famous work and one of the most celebrated of Renaissance Europe.

More was not the first to imagine an alternative civilization: Plato did so in his Republic , but More created a literary form that inquired into social conditions using vivid storytelling rather than theory. A poem at the start of the book hails Utopia's vision as surpassing Plato's because it goes beyond the abstract: ‘For what Plato's pen has plotted briefly, In naked words, as in a glass, The same have I performed fully, With laws, with men, and treasure fitly.’

More was born in London in 1478 and spent most of his life in the city. He became a lawyer of great distinction and held a variety of posts before becoming secretary to Henry VIII and in 1529, Lord Chancellor. Today he is remembered for his opposition to the king's divorce from Catherine of Aragon, which led to the break from Rome of the English church.

For refusing to bow to the king's wishes, More was executed in 1535. He became a legendary figure in British history, to many a faultless Catholic martyr. In our secular times, we prefer to view him as a hero of conscience who defended individual belief in the face of tyranny. With Utopia , he is seen as a social prophet whose vision for a better world continues to inspire. More was canonized by the Catholic Church in 1935. In 2000 Pope John Paul II declared him the patron saint of politicians.

In 1515, More was sent to Bruges as part of a diplomatic mission charged with settling a trade dispute between England and Flanders. During a lull in the talks, More visited Antwerp where he stayed with the town clerk, Peter Giles, with whom he developed a close friendship. Antwerp was then Europe's leading commercial city, and Giles one of its prominent officials and a highly learned man. The time in Antwerp had a stimulating effect on More. While at leisure there he conceived and began to write Utopia .

There appears, therefore, to have been an element of serendipity in the composition of Utopia , but in fact the ideas in it had been brewing in More's mind for years. By the time of the Bruges mission, More was a busy lawyer, and was Undersheriff of London. He had become a Member of Parliament and had negotiated on behalf of the Mercers' trading company, which represented wool and cloth merchants. These activities would have made More well aware of the social problems facing Tudor England as its commercial economy grew and traditional ways of life were displaced.

Steeped in theological and classical learning, More had become one of the most brilliant scholars of his day. When a young man, he had caught the attention of England's men of letters by delivering a series of lectures on The City of God , the vast work written at the end of the Roman Empire by the early Christian father, St Augustine of Hippo. Augustine's central idea was that of two cities that exist within human society: the worldly city of temporal desire and sin and the godly city of peace and fulfilment. Augustine was a major influence on More's spiritual development, and the idea of the two cities applied to social questions most likely fuelled the thinking that went into Utopia . A few years earlier, More had begun writing A History of Richard III , an account of the king whose defeat by Henry Tudor at Bosworth Field ushered in the Tudor reign. Richard's notoriety came in part from More's unflattering portrait of him in this work. Through Richard's story, the book deals with questions of tyranny and of sound kingship.

Utopia , then, was written by a man of considerable intellectual and practical credentials. More knew the law inside out, moved in the highest scholarly and court circles, and in his early works had already begun thinking about the pressing social and political problems of the day. Authors of the utopian tracts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries aimed their works at a wide audience, hoping that their ideas would be adopted in practical programmes of reform. Utopia 's sixteenth‐century audience was much narrower: the book was written for the elite Latin‐speaking scholars of Europe rather than the bakers and butchers of More's daily life in London.

Utopia takes the form of a traveller's tale told by a seafarer who once chanced upon the island of Utopia. During a series of dialogues with various interlocutors the explorer tells of life on the happy island and makes scathing critiques of English society. The story starts with real events and with More himself, who begins by telling of his mission to Flanders and his journey to Antwerp.

The fiction starts when More recalls one day stepping into the street after Mass and seeing Peter Giles talking to a sun‐beaten mariner. Giles tells him that the man, Raphael Hythloday, is a traveller with amazing tales of far‐off lands. The men retire to a garden and Raphael tells More and Giles about his travels generally, his views on the state of contemporary Europe, and about the distant nation of Utopia.

In Raphael's description of Utopia, we encounter a society that in some of its surface features resembles England. For example, like London, Utopia's capital city of Amaurot lies on a hill by a tidal river with a stone bridge over it. But at a deeper level Utopia is an inversion of the societies of England and Europe. In Utopia property is held in common and there is no money. Whenever a family needs food or clothes, the head of the household goes to the city warehouse and takes what is required. The Utopians are a disciplined, frugal people devoted to the higher pleasures of conversation and learning. They have no reason to take more goods than they need, having no desire to flaunt their possessions. Their sturdy houses have no locks on the doors and are exchanged every ten years by lot.

Читать дальше