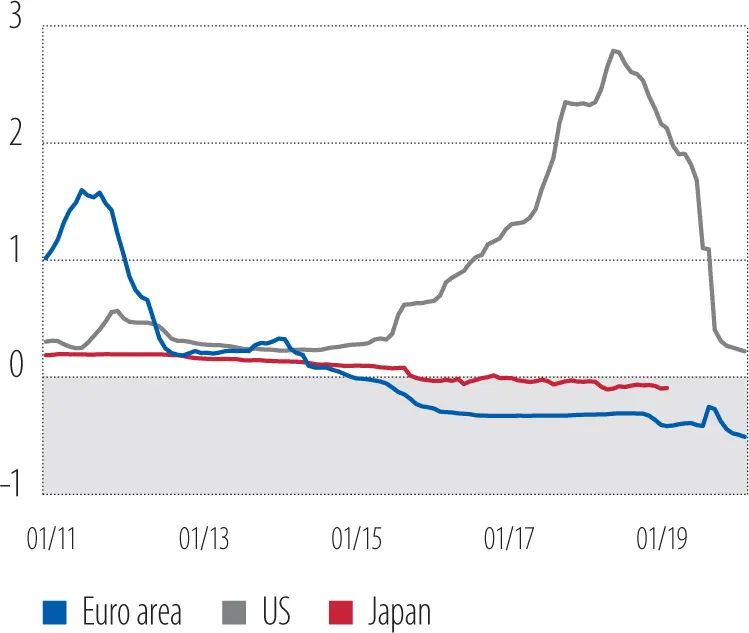

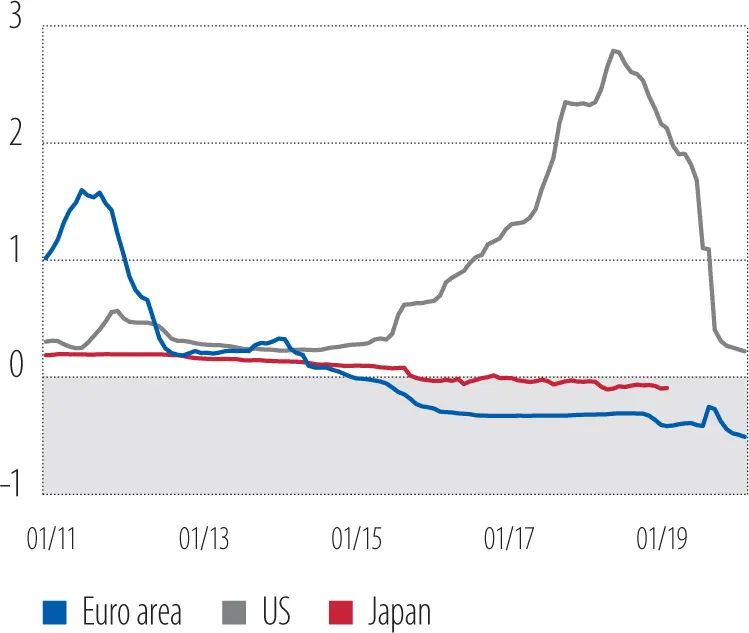

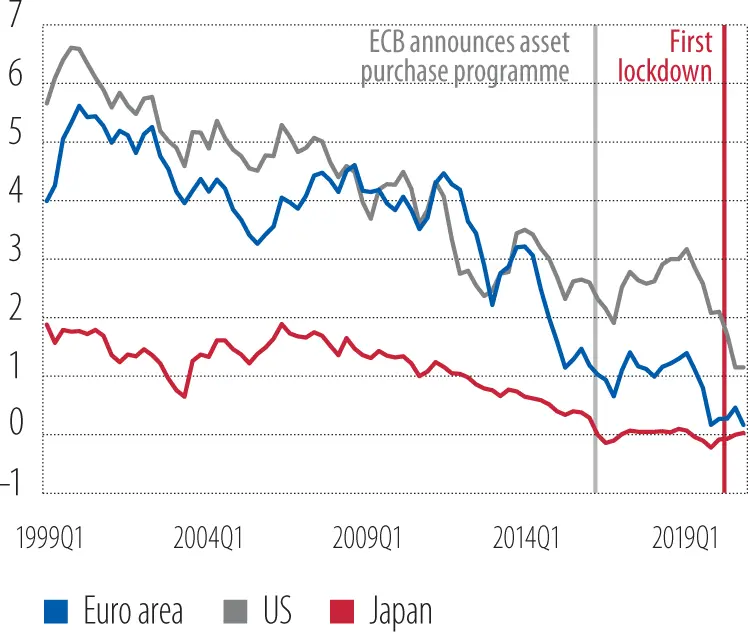

Long-term rates are most likely to remain low for longer, and might even drop further.While the rapid and unprecedented collapse of production, trade and employment may be reversed when the pandemic eases, historical data suggest that long-term economic consequences could persist (Jordà et al., 2020). Among these are a prolonged period of depressed real interest rates – akin to secular stagnation – that may linger for a long time. Chudik et al. (2020) estimate that the pandemic will likely drive long-term interest rates in the advanced economies about 100 basis points lower than their pre-COVID-19 lows over the next few years. This is because the crisis raises precautionary savings and dampens investment demand.

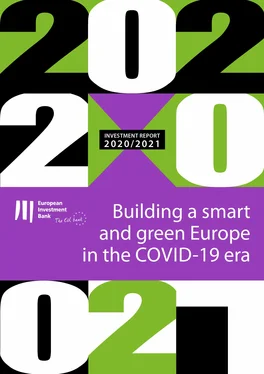

Figure 17

Short-term interest rates in selected advanced economies(% per year)

Source: Refinitv and EIB calculations.

Note: Last record October 2020.

Figure 18

Long-term interest rates in selected advanced economies(% per year)

Source: Refinitiv.

Note: Last record November 2020.

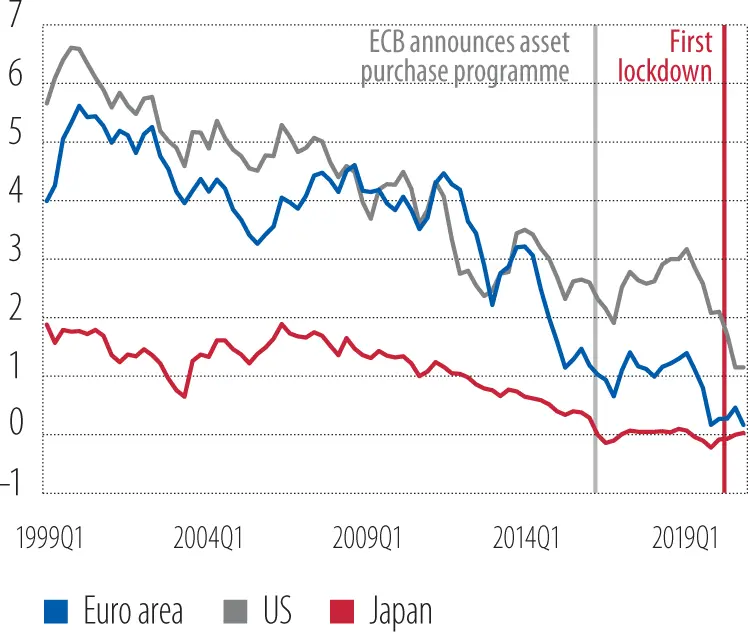

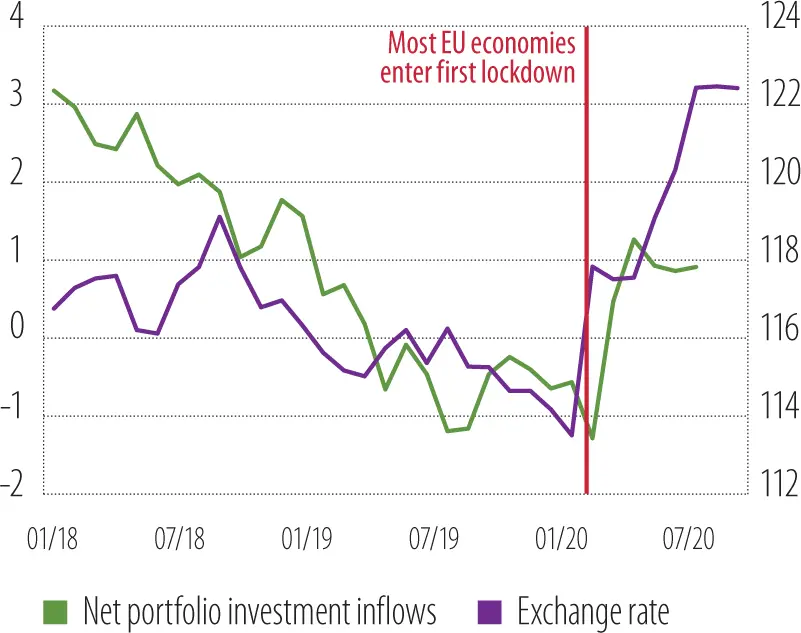

With increasing capital inflows and an appreciating exchange rate, Europe is perceived as resilient. Figure 19plots net portfolio inflows in the euro area and the euro effective exchange rate. Since the start of the crisis, both have clearly been on a positive trend. From February 2020 until October 2020, the effective exchange rate of the euro, the exchange rate against a basket of currencies, increased by 7%. The stronger exchange rate partly reflected the trend in cumulative annual capital flows, which increased by more than 2% of GDP over the same period, with a shift from net outflows to net inflows. These developments suggest that during the crisis, the European Union’s performance, which was partly the result of the policy response, was perceived as credible and reassuring by international investors. Over the same period, the European Commission issued the first tranche of bonds to finance the SURE instrument (Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency) and the recovery plan. The issuance was a major success, and was largely oversubscribed. This bodes well for the future of these bonds as a potential safe asset for investors, and also for the financing of the green transition.

A central bank with two arms

For the first time, the ECB acted both on monetary policy and on financial prudential policy.To ensure financial prudency, macro and micro policy measures were deployed. Following the global financial crisis, the ECB became in charge of the micro-supervision of euro area banks while the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) was created to coordinate macro-prudential policies across Europe. The COVID-19 crisis provided the first opportunity to coordinate these two types of policy intervention at the European level.

Figure 19

Net portfolio inflows and euro exchange rate(% GDP and index, 100=1999Q1)

Source: ECB and EIB calculations.

Note: Last record November 2020. An increase reflects an appreciation. Net portfolio inflows are reported using a 12-month moving average.

Figure 20

ECB lending to euro area credit institutions(in billions of euros)

Source: EIB Economics Department calculations based on IMF WEO.

Note: Last record 2019.

On the monetary policy side, the ECB deployed several measures to support banks’ liquidity.At the onset of the crisis, new non-targeted, longer-term refinancing operations were launched, the interest rates in targeted longer-term refinancing operations were lowered and collateral measures were eased (for a comprehensive presentation, see Lane, 2020). In June 2020, 742 European banks tapped the ECB’s TLTRO III for EUR 1.3 trillion. The multiyear loans are offered to banks at interest rates below the ECB’s main deposit rate, sometimes as low as minus 1% if certain conditions were met.[8] In net terms, after adjusting for the repayment of maturing loans, the June operation provided a liquidity injection of EUR 158 billion. From the start of the crisis until September 2020, liquidity injections for banks in the euro area almost tripled, increasing by almost EUR 1.2 trillion ( Figure 20). The ECB also decided on a new series of non-targeted pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations (PELTROs) to support liquidity in the euro-area financial system and to help preserve the smooth functioning of money markets by providing an effective liquidity backstop.

The ECB also strengthened its asset purchase programme.At the beginning of the crisis, the ECB increased its asset purchase programmes by EUR 870 billion (more than 7% of the euro area’s 2019 GDP) until end-2020. The Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), a new programme with an envelope of EUR 750 billion, was created, with eased conditions for eligibility. In June 2020, the programme was extended until June 2021 at least, with its envelope raised to EUR 1.35 trillion and maturing principal payments reinvested until the end of 2022 at least.

On the prudential regulation side, several measures were decided by the ECB, the European Commission and supervisory authorities to provide temporary capital relief for banks.Banks were allowed to operate below the level of capital defined by the Pillar 2 Guidance for the capital buffer and the liquidity coverage ratio. Supervisory flexibility regarding the treatment of non-performing loans was allowed and the capital requirements for market risk were reduced. To counteract the potentially destabilising impact of the more stringent banking regulations that were on the horizon, the implementation of certain new measures was frozen or postponed (ECB, 2020d).[9]

This extensive set of monetary and prudential measures proved very effective in keeping credit flowing.The coronavirus recession has resulted in large-scale changes to the balance sheets of euro-area banks. Corporate borrowers frontloaded their liquidity needs by taking out loans and placing the financing obtained in liquid assets, mostly held in commercial bank accounts. Banks significantly increased their funding from central banks while also building up their liquidity buffers there. The funding markets for banks have not shown the major signs of the distress they exhibited during the global financial crisis. In addition, most EU national governments provided state guarantees for bank loans, mainly targeting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In some countries these guarantees amount to more than 20% of GDP and represent over half of the existing stock of loans to non-financial corporations.

In Europe, central banks have retained their key roles, but are no longer the only major players.This time, governments and the European Commission have acted swiftly and strongly to cushion the economic shock caused by the pandemic with fiscal measures. Around EUR 2.7 trillion will be mobilised in response to the pandemic. This amount includes national liquidity measures, including the schemes approved under the temporary EU state aid rules, and measures taken under the flexibility arrangements of the EU budgetary rules (general escape clause).

Читать дальше