1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...36

1.3.4 Is It Minority Health or Health Disparities?

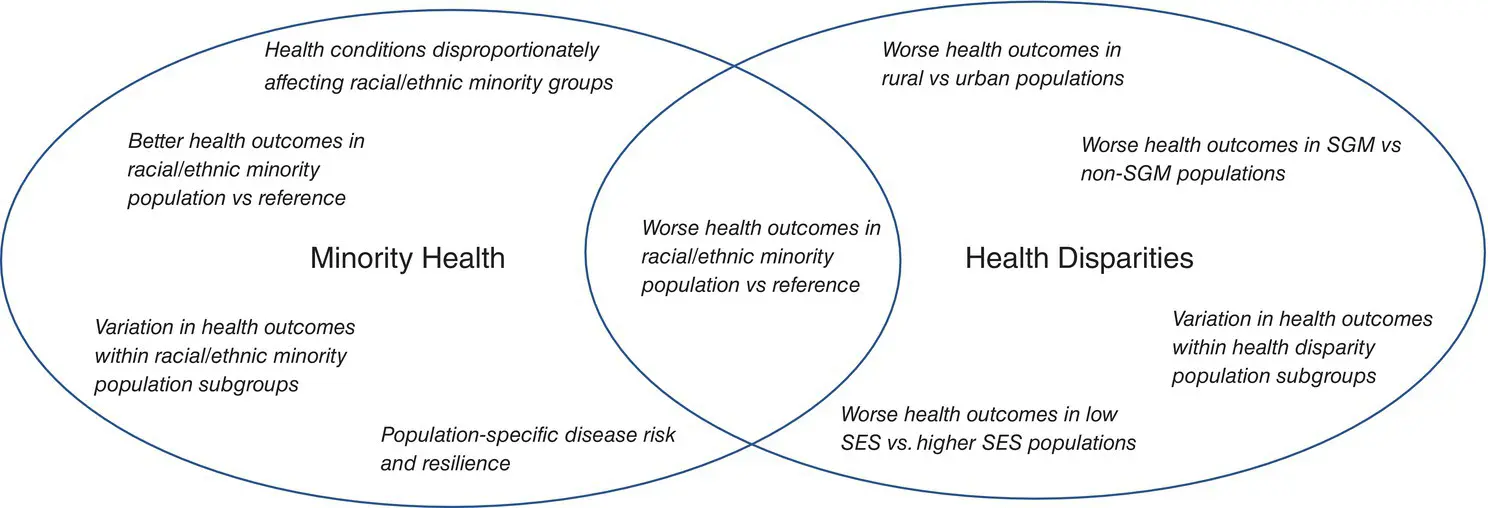

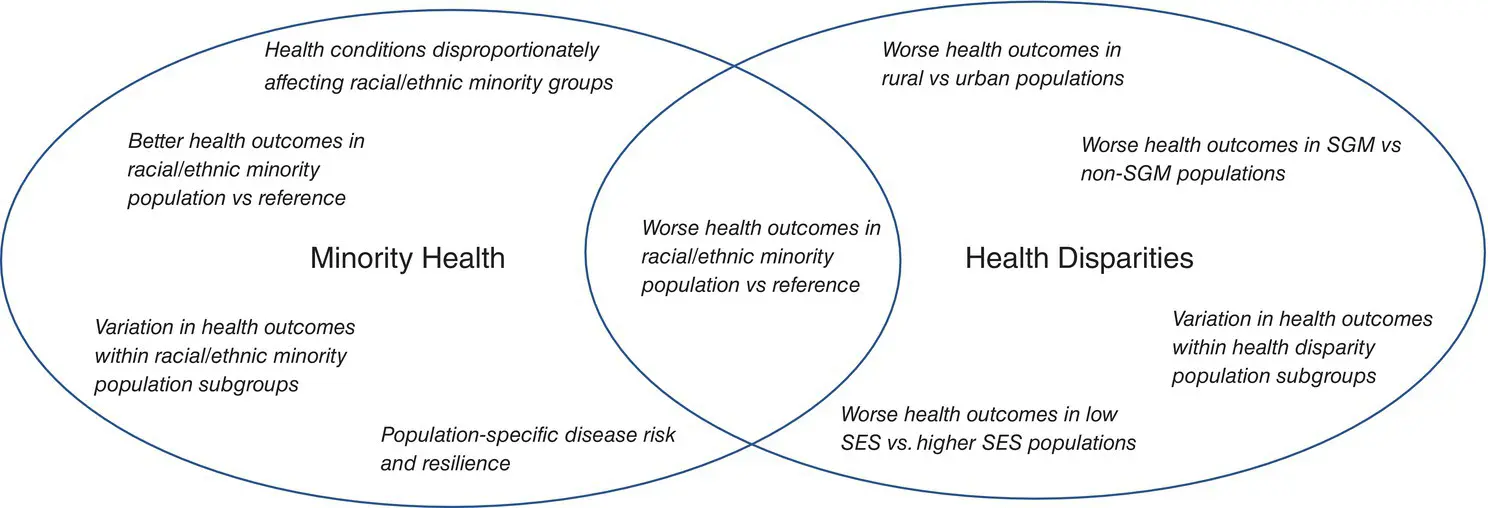

There is substantial overlap in minority health research and health disparities research, in particular, research that focuses on worse health outcomes among particular racial/ethnic minority groups compared to Whites or other populations ( Figure 1.1). For example, the fact that African American men have a higher prevalence and mortality for lung cancer is both a minority health and health disparities issue [4]. Blacks are a disparity population, smoke at a similar or lower rate than other racial/ethnic groups, and yet experience up to 50% more lung cancer for the same cigarette smoking intensity [4].

Figure 1.1 Overlapping but distinct constructs of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research.

Another example is type 2 diabetes, which is more common and has more severe manifestations in all racial/ethnic minority groups studied in the United States compared to Whites [5]. However, within a staff model healthcare system, the rates of myocardial infarction or heart attacks in patients with diabetes were lower for all minority race/ethnic groups compared to Whites, while the rates of end‐stage renal disease were higher. Understanding the factors that lead to these substantial differences in outcomes by race/ethnicity in a well‐characterized disease such as diabetes are likely to advance knowledge about mechanisms of how the condition progresses [6].

There are conditions where some racial/ethnic minority groups may have better health outcomes than the reference population, placing the study of these conditions within the domain of minority health research. Latinos or Hispanics have the longest life expectancy by gender of any other demographic group in the United States. This longer life expectancy is a consequence of lower overall rates of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cerebrovascular disease [7]. Suicide and opioid overdoses are other examples of conditions with lower rates for African Americans, Latinos, and Asians, but higher rates among American Indians/Alaska Natives and lower SES and rural Whites [8]. Research related to the last two populations would fall squarely into the category of health disparities research.

1.3.5 Standardized Measures of Minority Health‐ and Health Disparities‐Related Constructs

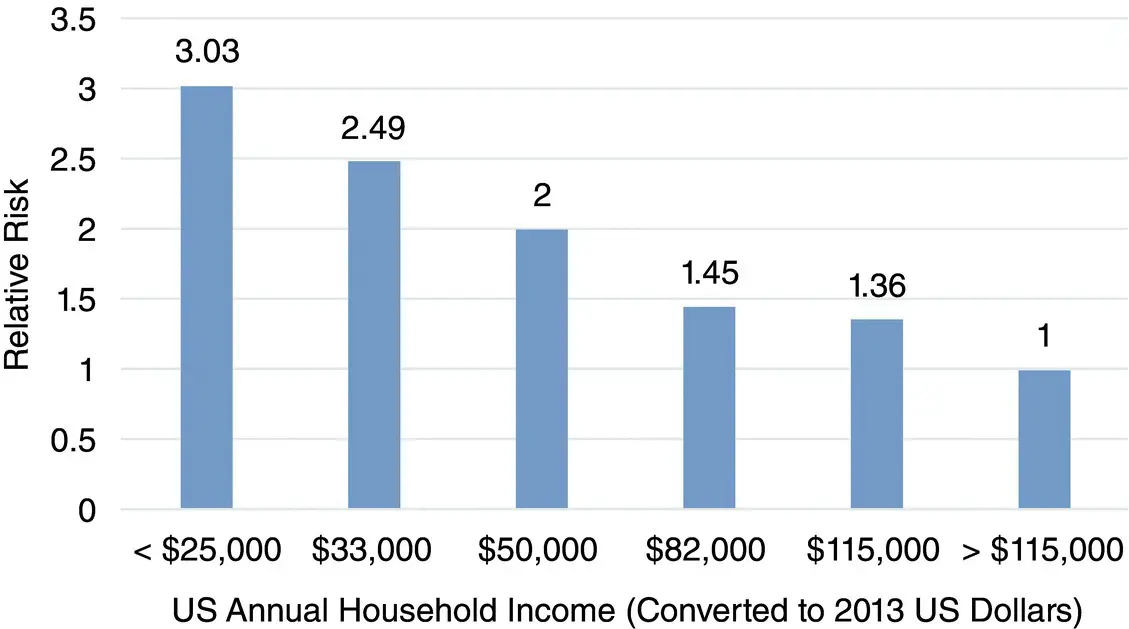

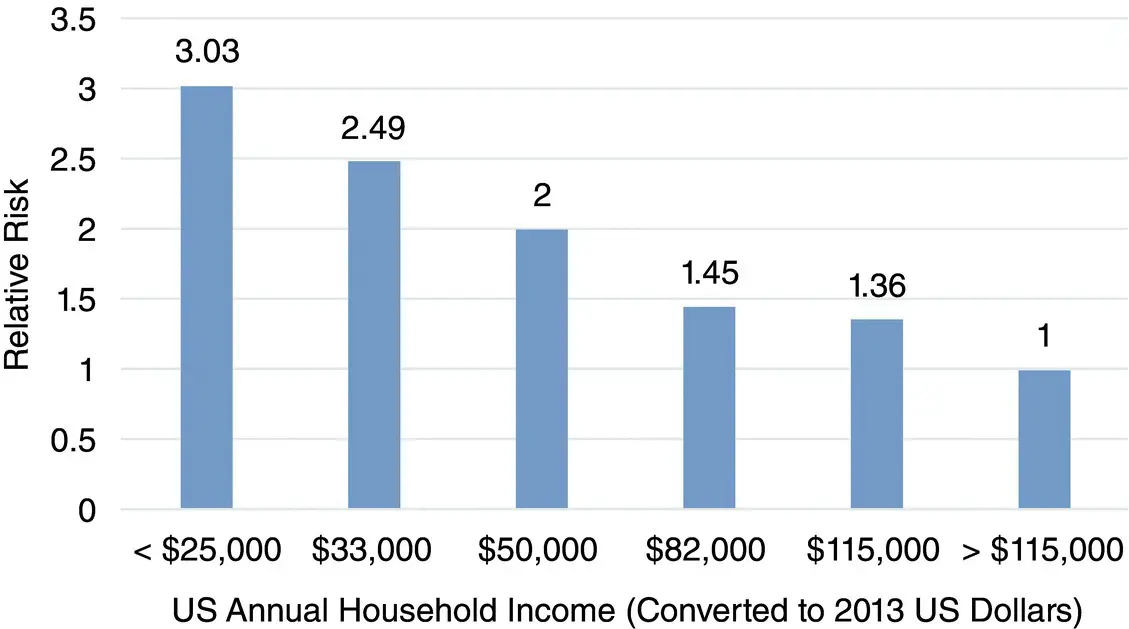

Evaluation of health disparities by SES requires a consistent and reliable approach. Household income is a powerful predictor of overall mortality in the United States, with those at the poverty level (defined as ≤ $25 000 household income per year) being three times more likely to die from any cause compared to the mortality rate among persons in a household with an income ≥ $115 000 per year ( Figure 1.2) [9]. Although household income is a useful measure of SES, formal years of education may be simpler to obtain, more reliable and stable over the life course, and overall more efficient. Education may also be incorrectly reported, and years of schooling do not equate to quality of education. Thus, depending on the research question at hand, multiple indicators of SES may be the best strategy [10]. This relationship of SES measures and health outcomes is most robust for Whites and Blacks, but there is evident interaction between SES and race/ethnicity that needs to be inherent in most studies focused on minority health and health disparities.

Figure 1.2 Relative risk of all‐cause mortality by US annual household income level.

Although health disparities are usually related to SES and traditional minority race/ethnic groups, people living in rural areas are also a minority in their own way. There is increasing evidence of disparities from the leading causes of death among persons living in the most rural areas compared to those living in cities and these disparities merit increased research attention [11]. The operational definition of rurality used in data reported from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention categorized about 18% of the US population as residing in rural counties. NIMHD endorses this definition and encourages researchers to examine the intersectionality of rural residence, less privileged SES, and race/ethnic minorities.

The addition of sexual and gender minorities (SGM) as a health disparity population is expected to lead to more innovative research to examine health determinants that contribute to disparities. SGM populations share the experience of discrimination with other disparity populations. This implies that there may be shared mechanisms of health determinants to specific conditions that can be examined. Although sexual orientation and gender identity questions are more recent additions to national surveys, it is clear that how these questions are asked significantly affects how respondents identify themselves. More research is needed to understand the best ways to assess sexual orientation and gender identity.

In comparing outcomes across populations, it is important to use standard terminology. Disease or condition rates, important aspects of morbidity, are typically described in terms of incidence and/or prevalence and are important components of population morbidity. Population health is often measured by mortality, so researchers will frequently evaluate not only rates, but also whether a population has premature and/or excessive mortality for specific conditions. Using a general index that reflects population health—such as a global burden of disease measured by disability‐adjusted life years (DALYS) or premature years of life lost—can provide insights into understanding mortality patterns in areas where populations vary [12].

For clinicians, rates of risk factors such as level of blood pressure, health‐related behaviors such as cigarette smoking, and biomarkers linked to disease outcomes such as glycosylated hemoglobin for diabetes are important components of population morbidity directly in the causal pathway of disease incidence. For clinicians and social scientists, the assessment of how patients or people feel and function using standardized measures provides important data and outcomes to consider. Such outcomes could include psychometrically tested symptom scores for specific conditions, quality of life measures, and activities of daily living. The interdisciplinary nature of minority health and health disparities science will benefit from concurrence on standardized terminology and measures.

1.4 The NIMHD Research Framework: Health Determinants in Action

There is no single identifiable mechanism or etiologic pathway for observed health or healthcare disparities. The robust association of SES with overall mortality underlies all other factors studied. If SES could be made equal across society, would health disparities be eliminated? If access to care were similar for all groups in terms of accessibility, cost and quality, would healthcare outcomes differ by SES or race/ethnicity? Opportunity in education and employment and access to quality healthcare will go a long way to addressing health and healthcare disparities, but other factors will continue to affect outcomes. Understanding complex interactions that may lead to health disparities, such as biological processes and genetics, cultural influences on individual behaviors and lifestyle, effects of the physical and social environment, and access to and interaction with the healthcare system all may play significant roles depending on the populations and conditions. To depict the wide array of determinants that promote or worsen minority health and/or cause, sustain, or reduce health and healthcare disparities, NIMHD scientific staff developed the NIMHD Research Framework (also referred to here as the Framework). 4

Читать дальше