Joyce lived near the beach, beside the spread lines of the Egyptian troops, in an imposing array of large tents and small tents, and we talked over things done or to do. Every effort was still directed against the railway. Newcombe and Garland were near Muadhdham with Sherif Sharraf and Maulud. They had many Billi, the mule-mounted infantry, and guns and machine-guns, and hoped to take the fort and railway station there. Newcombe meant then to move ahl Feisal's men forward very close to Medain Salih, and, by taking and holding a part of the line, to cut off Medina and compel its early surrender. Wilson was coming up to help in this operation, and Davenport would take as many of the Egyptian army as he could transport, to reinforce the Arab attack.

All this programme was what I had believed necessary for the further progress of the Arab Revolt when we took Wejh. I had planned and arranged some of it myself. But now, since that happy fever and dysentery in Abdulla's camp had given me leisure to meditate upon the strategy and tactics of irregular war, it seemed that not merely the details but the essence of this plan were wrong. It therefore became my business to explain my changed ideas, and if possible to persuade my chiefs to follow me into the new theory.

So I began with three propositions. Firstly, that irregulars would not attack places, and so remained incapable of forcing a decision. Secondly, that they were as unable to defend a line or point as they were to attack it. Thirdly, that their virtue lay in depth, not in face.

The Arab war was geographical, and the Turkish Army an accident. Our aim was to seek the enemy's weakest material link and bear only on that till time made their whole length fail. Our largest resources, the Beduin on whom our war must be built, were unused to formal operations, but had assets of mobility, toughness, self-assurance, knowledge of the country, intelligent courage. With them dispersal was strength. Consequently we must extend our front to its maximum, to impose on the Turks the longest possible passive defence, since that was, materially, their most costly form of war.

Our duty was to attain our end with the greatest economy of life, since life was more precious to us than money or time. If we were patient and superhuman-skilled, we could follow the direction of Saxe and reach victory without battle, by pressing our advantages mathematical and psychological. Fortunately our physical weakness was not such as to demand this. We were richer than the Turks in transport, machine-guns, cars, high explosive. We could develop a highly mobile, highly equipped striking force of the smallest size, and use it successively at distributed points of the Turkish line, to make them strengthen their posts beyond the defensive minimum of twenty men. This would be a short cut to success.

We must not take Medina. The Turk was harmless there. In prison in Egypt he would cost us food and guards. We wanted him to stay at Medina, and every other distant place, in the largest numbers. Our ideal was to keep his railway just working, but only just, with the maximum of loss and discomfort. The factor of food would confine him to the railways, but he was welcome to the Hejaz Railway, and the Trans-Jordan railway, and the Palestine and Syrian railways for the duration of the war, so long as he gave us the other nine hundred and ninety-nine thousandths of the Arab world. If he tended to evacuate too soon, as a step to concentrating in the small area which his numbers could dominate effectually, then we should have to restore his confidence by reducing our enterprises against him. His stupidity would be our ally, for he would like to hold, or to think he held, as much of his old provinces as possible. This pride in his imperial heritage would keep him in his present absurd position--all flanks and no front.

In detail I criticized the ruling scheme. To hold a middle point of the railway would be expensive for the holding force might be threatened from each side. The mixture of Egyptian troops with tribesmen was a moral weakness. If there were professional soldiers present, the Beduin would stand aside and watch them work, glad to be excused the leading part. Jealousy, superadded to inefficiency, would be the outcome. Further, the Billi country was very dry, and the maintenance of a large force up by the line technically difficult.

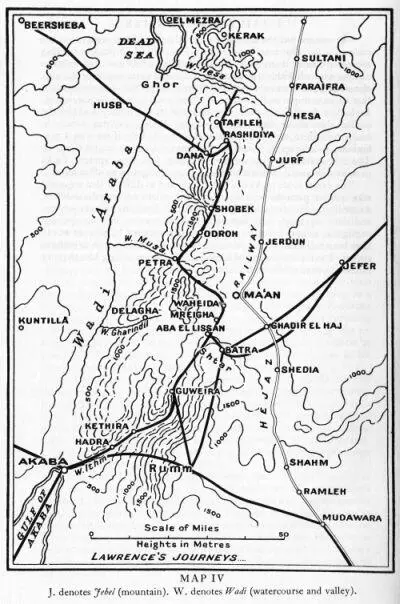

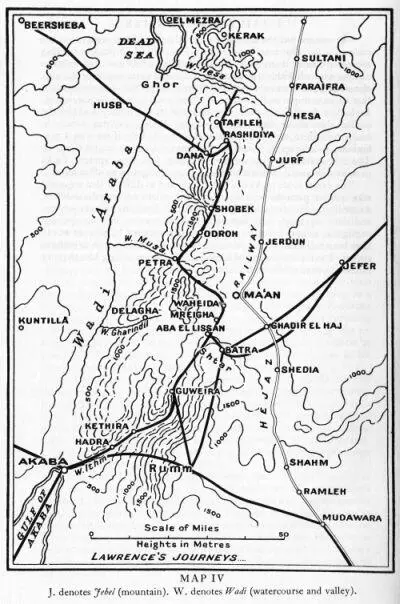

Neither my general reasoning, however, nor my particular objections had much weight. The plans were made, and the preparations advanced. Everyone was too busy with his own work to give me specific authority to launch out on mine. All I gained was a hearing, and a qualified admission that my counter-offensive might be a useful diversion. I was working out with Auda abu Tayi a march to the Howeitat in their spring pastures of the Syrian desert. From them we might raise a mobile camel force, and rush Akaba from the eastward without guns or machine-guns.

The eastern was the unguarded side, the line of least resistance, the easiest for us. Our march would be an extreme example of a turning movement, since it involved a desert journey of six hundred miles to capture a trench within gunfire of our ships: but there was no practicable alternative, and it was so entirely in the spirit of my sick-bed ruminations that its issue might well be fortunate, and would surely be instructive. Auda thought all things possible with dynamite and money, and that the smaller clans about Akaba would join us. Feisal, who was already in touch with them, also believed that they would help if we won a preliminary success up by Maan and then moved in force against the port. The Navy raided it while we were thinking, and their captured Turks gave us such useful information that I became eager to go off at once.

The desert route to Akaba was so long and so difficult that we could take neither guns nor machine-guns, nor stores nor regular soldiers. Accordingly the element I would withdraw from the railway scheme was only my single self; and, in the circumstances, this amount was negligible, since I felt so strongly against it that my help there would have been half-hearted. So I decided to go my own way, with or without orders. I wrote a letter full of apologies to Clayton, telling him that my intentions were of the best: and went.

Map 4

Map 4

Book Four.

Extending to Akaba

Table of Contents

Chapters XXXIX to LIV

The port of Akaba was naturally so strong that it could be taken only by surprise from inland: but the opportune adherence to Feisal of Auda Abu Tayi made us hope to enrol enough tribesmen in the eastern desert for such a descent upon the coast. Nasir, Auda, and I set off together on the long ride. Hitherto Feisal had been the public leader: but his remaining in Wejh threw the ungrateful load of this northern expedition upon myself. I accepted it and its dishonest implication as our only means of victory. We tricked the Turks and entered Akaba with good fortune.

Table of Contents

By May the ninth all things were ready, and in the glare of mid-afternoon we left Feisal's tent, his good wishes sounding after us from the hill-top as we marched away. Sherif Nasir led us: his lucent goodness, which provoked answering devotion even from the depraved, made him the only leader (and a benediction) for forlorn hopes. When we broke our wishes to him he had sighed a little, for he was body-weary after months of vanguard-service, and mind-weary too, with the passing of youth's careless years. He feared his maturity as it grew upon him, with its ripe thought, its skill, its finished art; yet which lacked the poetry of boyhood to make living a full end of life. Physically, he was young yet: but his changeful and mortal soul was ageing quicker than his body-going to die before it, like most of ours.

Читать дальше

Map 4

Map 4