The major factors considered in the study were as follows:

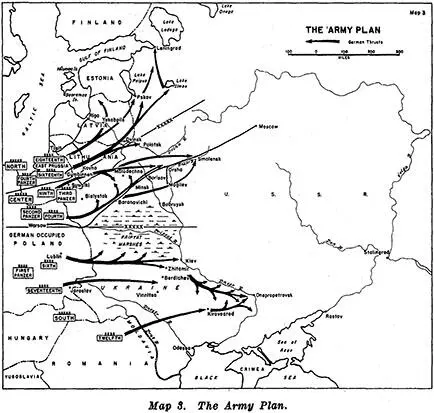

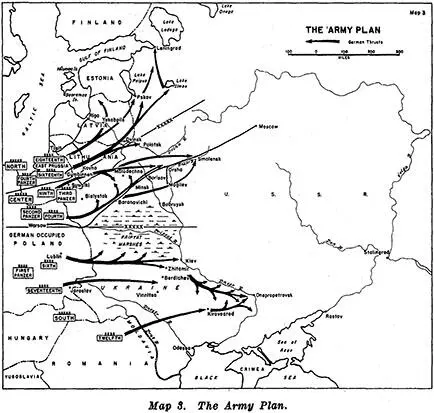

a. Manpower. The ratio of strength between German and Russian forces was not at all favorable. Against the approximately 170 Soviet divisions plus ample reinforcements estimated to be stationed in western Russia the Germans could at best put only 145 — including 19 armored divisions — into the field. Small contingents of Romanian and Finnish forces could be added to this total, but their equipment, capabilities, and combat efficiency were below the German. In other words, the German offensive forces would not have the advantage of numerical superiority. The only method of compensating for this deficiency was to mass forces at crucial points and take risks at others.

The relative combat efficiency was not as clear cut. To be sure, the German forces had had more combat experience; their leaders were experienced in maneuvering large motorized forces, and the individual soldier was self-confident. The Russian soldier, however, was not to be underestimated, and it remained doubtful whether the Red Army would show immediate signs of internal disintegration. On the other hand, Russian leadership was certainly below the German average, particularly in making quick decisions in a war of movement.

The element of surprise in launching the attack would probably compensate for some of the German numerical inferiority. Extensive deceptive measures were to be taken to achieve surprise, but Hitler's pretext that preparations along the Russian border were merely a deliberate deception to divert British attention from an imminent invasion of England could not be maintained indefinitely. In the final analysis, surprise was limited to the timing and direction of the German attack; to hope for more seemed unrealistic.

b. Space. The tremendous width and depth of European Russia was another problem that deserves serious consideration, especially in view of the disproportion of strength. Everything would depend on the German Army's ability to prevent the Russians from exploiting this space advantage. Whether they would give battle near the border or attempt an organized withdrawal could not be foreseen. In any event, it was essential to engage the enemy as soon as possible, if his quick destruction was to be achieved. The distribution of the German forces and the application of deceptive measures had to conform with this intention. The Russians had to be denied any opportunity to withdraw into the depths of European Russia where they could fight a series of delaying actions. This objective could be attained only by strict application of the principles of mass, economy of force, and movement. Substantial Russian forces were to be cut off from their rear communications and forced to fight on reversed fronts. This was the only method by which the German Army could cope with the factor of space during the offensive operations. Lacking the necessary forces, the German Army could not mount an offensive along the entire front at the same time, but had to attempt to open gaps in the front at crucial points, envelop and isolate Russian forces, and annihilate them before they had a chance to fall back.

c. Time. The problem of selecting the most propitious time assumed far more importance than on any previous occasion. For operations in Russia the May-to-October period only seemed to offer a reasonable guarantee of favorable weather. The muddy season began in late October, followed by the dreaded Russian winter. The campaign had to be successfully concluded while the weather was favorable, and distances varying from five to six hundred miles had to be covered during this period. From the outset the German campaign plan would be under strong pressure of time.

d. Inteligence Information. The intelligence picture revealed two major Russian concentrations — one in the Ukraine of about 70 divisions and the other in White Russia near and west of Minsk of some 60 divisions. There appeared to be only 30 divisions in the Baltic States.

The disposition of the Red Army forces did offer the Soviets the possibility of launching an offensive in the direction of Warsaw. But, if attacked by Germany, it was uncertain whether the Russians would make a stand in the border area or fight a delaying action. It could be assumed, though, that they would not voluntarily withdraw beyond the Dnepr and Dvina Rivers, since their industrial centers would remain unprotected.

e. Analysis of Objective Area. The almost impassable forests and swamps of the Pripyat Marshes divided the Russian territory west of the Dnepr and Dvina Rivers into two separate theaters of operation. In the southern part the road net was poor. The main traffic arteries followed the river courses and therefore ran mostly in a north-south direction. The communication system north of the Pripyat Marshes was more favorable. The best road and rail nets were to be found in the area between Warsaw and Moscow, where the communications ran east and west and thus in the direction of the German advance. The traffic arteries leading to Leningrad were also quite favorable. A rapid advance in the south would be hampered by major river barriers — the Dnestr, the Bug, and the Dnepr — whereas in the north only a single river, the Dvina, would have to be crossed. By thrusting straight across the territory north of the Pripyat one could strike at Moscow. The Red Army would not simply abandon the Russian capital, and in the struggle for its possession the Germans could hope to deliver a telling blow.

By contrast, the area south of the Pripyat region was of minor military importance; there the Soviets could more readily trade space for time and withdraw to a new line, possibly behind the Dnepr River. On the other hand, the south offered tempting economic targets, such as the wheat of the Ukraine, the coal fields of the Donets Basin, and the faraway oil of the Caucasus. The Army's immediate interest, however, was to attain military victory, not economic advantages. The quicker the campaign was over the more decisive the victory, the more certain would be the eventual accrual of economic advantages.

For these reasons the Operations Division arrived at the conclusion that the main effort should be concentrated north of the Pripyat Marshes and that the principal thrust should be directed via Smolensk toward Moscow.

The Preliminary Plan

(November-5 December 1940)

Table of Contents

During November the Army High Command was primarily concerned with preparations for an attack on Gibraltar and armed intervention on the Balkan Peninsula. At the same time, the training and equipment of the newly activated divisions proceeded according to schedule. Molotov's visit in Berlin on 12-13 November aroused some hope that Hitler's intentions might be modified by a change in Soviet policy. When Admiral Raeder saw the Fuehrer on the day after Molotov's departure, he found that Hitler continued to plan for an attack on Russia. Raeder suggested that such a conflict be delayed until a victory had been won over Britain. His reasons were that a war with the Soviet Union would involve too great an expenditure of German strength and that it was impossible to foretell where it would end. Raeder then explained that the Soviets were dependent on German assistance for building up their navy and would therefore not attack Germany for the next few years.

In November the Soviet Government made the first official inquiry at the German Embassy in Moscow with regard to German troop concentrations in the former Polish provinces adjacent to the Russian border. General Koestring, the German military attaché, was called to Berlin, where he was instructed to reply that the troop movements were incidental to the redeployment after the campaign in the West, the requirements of the occupation, and the better training facilities available in this area.

Читать дальше