1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...24 Nevertheless, the suppression of complementarity in some cases may help to obscure the unfairness and oppressive potential of the system of duty as a whole; theoretically, at least, parents and husbands, too, must do their duty even to bad children and wives. Therefore, in contrast to complementarity, reciprocity is emphasized by AllestreeAllestree, Richard and DelanyDelany, Patrick, correspondent of Richardson. It is noteworthy, however, that it is ‘conceptual’, rather than ‘actual’, reciprocity that matters to them. In GouldnerGouldner, Alvin W.’s terms,

[s]pecific and complementary duties are owed by role partners to one another by virtue of the socially standardized roles they play. These may require an almost unconditional compliance in the sense that they are incumbent on all those in a given status simply by virtue of its occupancy. In contrast, the generalized norm of reciprocity evokes obligations toward others on the basis of their past behavior. (59)

The duties of parents and children, for example, are reciprocal in so far as each side owes the other certain benefits; however, each side is obliged to confer such benefits whether or not they also receive any. For AllestreeAllestree, Richard and DelanyDelany, Patrick, correspondent of Richardson, status duties are structured according to norms of reciprocity, but are severed from them in actual practice. This can be done, in part, because benefits conferred on other human beings are conceptualized as being mostly returns for divine benefits. That is, while social duties are structured according to the norm of reciprocity, actual reciprocal exchange takes place mostly, and matters most, in the relationship of the divine and the human. For example, since God is the source of “all our plenty”, and since this gift cannot be repaid directly, “whatever we should by way of thankfulness give back again unto God, our alms is the way of doing it” (AllestreeAllestree, Richard 374; Sunday XVII). The person receiving alms may have done nothing to deserve them, but this is unimportant compared to the exchange taking place between God and the donor of charity. Practical reciprocity is brought in, on the one hand, to emphasize God’s mercy in contrast to the poor returns that men are able to make; incidentally, men are so sinful that even the best can have no right to divine beneficence. On the other hand, reciprocity acts as an additional incentive for the performance of one’s duty. Although there may be parents, as AllestreeAllestree, Richard concedes, who neglect and tyrannize their children, most confer (god-like) benefits that no child can expect to repay (Allestree 299; Sunday XIV).

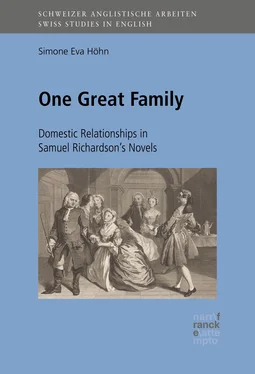

Richardson largely shared the values outlined in The Whole Duty of Man ; indeed, both his novels and his letters provide ample evidence of this.12 Nevertheless, his works also problematize the system of duty. They do this, on the one hand, by emphasizing the misery of the victims of the system – often barred from self-defence by the very principles which are trampled on by their oppressors – and, on the other hand, by presenting his heroines as the centre of a network of duties which they try to negotiate. This is less true of the hero; although Sir Charles is shown as successfully fulfilling all his duties, he is rarely depicted facing contradictory obligations.13 As a man, moreover, he escapes some of the conflicts which Pamela and Clarissa have to confront. The Whole Duty of Man does not explicitly gender its reader; the “man” of the title is a human being, who may be either a woman (who needs to pay attention to a wife’s duties) or a man. However, this apparently neutral gendering actually obscures the differences in the situations of women and men – just as modern gender-neutral language may obscure this today (cf. PatemanPateman, Carol 16–7). Edward YoungYoung, Edward, correspondent of Richardson “called Clarissa ‘ The Whole Duty of WOMAN ’”, implicitly, and perhaps unconsciously, drawing attention to the fact that the “whole duty” of an individual is partly gender-based (qtd. in EavesEaves, T.C. Duncan and Ben D. Kimpel & Kimpel 286).14 In Richardson’s hands, then, the individual is feminised.15 The system of duty now takes on an ambivalent function: it constrains women by limiting the heroines’ options of rebellion, but it also empowers them by validating some forms of disobedience.

1.2 Clarissa and the system of duty

The problem of (reciprocal) duty appears most prominently, and most problematically, in Richardson’s second novel, although it also features in various discussions in Grandison . The presentation of few fictional heroines is as focused on universal “duty” and usefulness as that of Clarissa Harlowe. In contrast, Richardson’s Harriet Byron is shown in those social relationships and moral struggles which are least connected to status duties, and Clementina’s struggles are, for the most part, far removed from quotidian duties, let alone household tasks. It is unclear if either of them takes part in managing the house, while much is made of Clarissa’s housekeeping. Pamela is closest to Clarissa in that especially her life after marriage centres on her responsibilities as mistress of a family and wife of a rakish man. The presentation of duty and of conflicts of duty, however, is quite different (cf. part II).

At the same time, it should be emphasized that, if few heroines are defined by dutifulness and useful self-organization as Clarissa is, there are also few as explicitly intent on guarding both their “free will” and their private time and space (cf. also SpacksSpacks, Patricia Meyer, Privacy 16–8). With regard to the first, Clarissa goes so far as to accuse Solmes of intending her dishonour, “if endeavouring to force a free mind is to dishonour it!” (323). (At this point, she still refuses to consider the possibility that her “honour” may be threatened in a more conventional sense). Throughout most of the novel, Clarissa also defends her private space, not only as a sanctuary from her family’s and Lovelace’s oppression, but as a space of meditation and (epistolary) communication. Michael SuarezSuarez, Michael F. draws attention to the fact that Lovelace “understands that what she really wants is autonomy; accordingly, he routinely promises Clarissa the freedom that she is denied at home” (75). In marked contrast to his promises, one of their earliest quarrels is brought on when he grudges her the time she spends writing to Anna – an issue which comes up repeatedly (420).

After Clarissa’s death, Anna describes her usual distribution of her private time before the conflict with her family. Significantly, the division she makes is based on a “self-set lesson” and includes considerations of duty as well as of pleasure (1470). Her short night – six hours of sleep only, like Lovelace (74) –, Anna explains, is for her a cordial rather than a mortification: “She thought herself not so well, and so clear in her intellects (so much alive , she used to say) if she exceeded this proportion” (1470).1 Most of her hours are allotted to social engagements in the broadest sense (including household management and visits to the poor), yet the first three are for “closet-duties” and letter writing. Despite the apparent strictness of Clarissa’s self-imposed system, she is always ready to “ borrow , as she called it, from other distributions” (1470) in order to gratify her family or visitors. Her – or Anna’s – terminology highlights the way in which such accommodation constitutes private time: her hours are Clarissa’s to distribute and manage, just as she manages the money from which she donates alms. Her daily schedule is in accordance with contemporary conduct books for women (cf. KukorellyKukorelly Leverington, Elizabeth, “Domesticating the Hero” 157), yet the emphasis is consistently on “choice”. Indeed, Clarissa emphasises that she does not regard her strict time-keeping as a duty, “but when it is more pleasant to me to keep such an account than to let it alone; why may I not proceed in my supererogatories?” (1472). This is one of the ways in which the system of duty is presented as one which enables good women: Clarissa expresses her individuality through acting on the best rules known to her. Like Richardson’s other heroines, she “defines herself through the ability to make moral and rational choices, and this is true even when the power of acting on such choice is obstructed” (LatimerLatimer, Bonnie, Making Gender 71).

Читать дальше