Haunted by the dread of removal to San Carlos, the appearance of a party of Grant County officials at the Mescalero agency on a hunting tour a few months later caused Victorio and his band to flee with a number of Chiricahua and Mescaleros to the mountains of southern New Mexico.

For two years, until he met his death at the hands of Mexican troops in the fall of 1880, Victorio spread carnage throughout the southern portions of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, and the northern states of Mexico, enlisting the aid of every willing renegade or refugee of whatever band or tribe in that section. After him Nané, Chato, Juh, Geronimo, and other doughty hostiles carried the fighting and raiding along until June, 1883, when Crook, reassigned to the Arizona district, followed the Chiricahua band under Geronimo into the Sierra Madre in Chihuahua, whence he brought them back whipped and ready to accept offers of peace. The captives were placed upon the San Carlos and White Mountain reservations, where, with the various other Apache bands under military surveillance, and with Crook in control, they took up agriculture with alacrity. But in 1885 Crook's authority was curtailed, and through some cause, never quite clear, Geronimo with many Chiricahua followers again took the warpath. Crook being relieved at his own request, Gen. Nelson A. Miles was assigned the task of finally subduing the Apache, which was consummated by the recapture of Geronimo and his band in the Sierra Madre in September, 1886. These hostiles were taken as prisoners to Florida, later to Alabama, and thence to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where, numbering 298, they still are, living as farmers in peace and quiet, but still under the control of the military authorities.

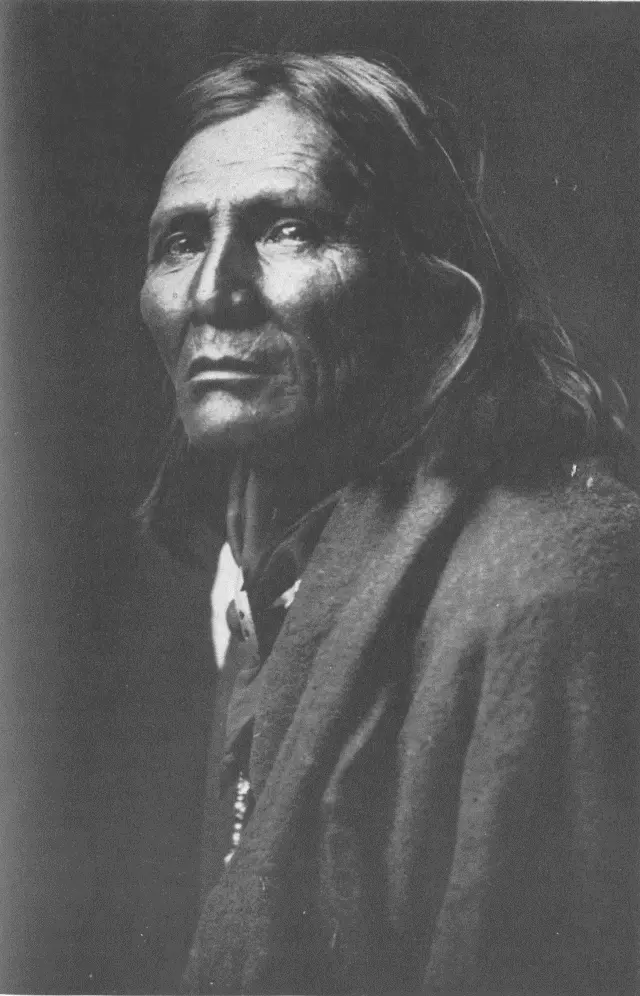

Alchĭsé - Apache

One of the last hostile movements of note was the so-called Cibicu fight in 1882. In the spring of that year an old medicine-man, Nabakéltĭ, Attacking The Enemy, better known as Doklínĭ, started a "medicine" craze in the valley of the Cibicu on the White Mountain reservation. He had already a considerable following, and now claimed divine revelation and dictated forms of procedure in bringing the dead to life. As medicine paraphernalia he made sixty large wheels of wood, painted symbolically, and twelve sacred sticks, one of which, in the form of a cross, he designated "chief of sticks." Then with sixty men he commenced his dance.

One morning at dawn Nabakéltĭ went to the grave of a man who had been prominent in the tribe and who had recently died. He and his adherents danced about the grave and then dug up the bones, around which they danced four times in a circle. The dancing occupied the entire morning, and early in the afternoon they went to another grave, where the performance was repeated. In each instance the bones were left exposed; but later four men, specially delegated, went to the graves and erected a brush hut over the remains.

Nabakéltĭ told the people that they must pray each morning for four days, at the end of which time the bleached bones would be found clothed with flesh and alive again. By the end of the second day the Apache band on the Cibicu became excited almost to the degree of frenzy. They watched the little grave-houses constantly and gathered in groups about other graves.

Some of the Apache employed as scouts with the detachment stationed at Fort Apache heard of the craze and obtained leave of absence to investigate. They returned and informed the commanding officer, then acting as agent, that their people were going mad, whereupon a number of scouts and troopers were sent to learn the cause of the trouble and to ask Nabakéltĭ to come to the fort for an interview. Though angered by the message, the old man agreed to come in two days. Meanwhile he had the little brush houses over the bones tightly sealed to keep out preying animals and curious Indians. He then explained to his people that, owing to the interruption by the whites, it was probable that the bones would not come to life at the end of four days, as predicted, but that he would make a new dance later and prove the efficacy of his creed.

Then he started for the fort with his entire band of dancers, sixty-two in number, each with his "sacred medicine"—wheels, sticks, and drums. They journeyed afoot, stopping occasionally to dance, and reached the grounds of the fort late in the afternoon of the second day. On they passed, dancing in a spectacular manner, and camped that night on the flat a little above the fort, where they waited for someone to come over to interview them. The agent did not send for Nabakéltĭ that night, so at daybreak he started up White river with his band, passing by the present agency site, and crossing into Bear Springs valley. Thence they took the trail toward the Cibicu again, reaching the Carrizo in the evening, where they camped for the night and performed another dance. The following morning they took the trail for their home, which they reached rather early in the day.

As soon as the band had reached its destination, another summons was delivered to Nabakéltĭ to appear before the agent at the fort. This time the old man sent back word that he would not come: he had gone once, and if any had wished to see him, they had had their chance.

On receipt of this reply, sixty mounted soldiers, armed and provisioned, were sent over to the Cibicu to put a stop to the dancing. Apache scouts had been stationed to watch the manœuvres of the Indians and to keep the officials informed. They met the troopers, who made a night ride to the stream, and informed them where the old medicine-man was encamped. Early in the morning the soldiers reached the Cibicu at a point about two miles above Nabakéltĭ's camp, whence a detachment was despatched to arrest the medicine-man and bring him to the place where headquarters were being established. It was the intention merely to arrest and hold him while the troops rested for the day, preparatory to taking him back to the fort; but it was deemed necessary to send a force sufficiently large to cope with the Indians should they attempt resistance.

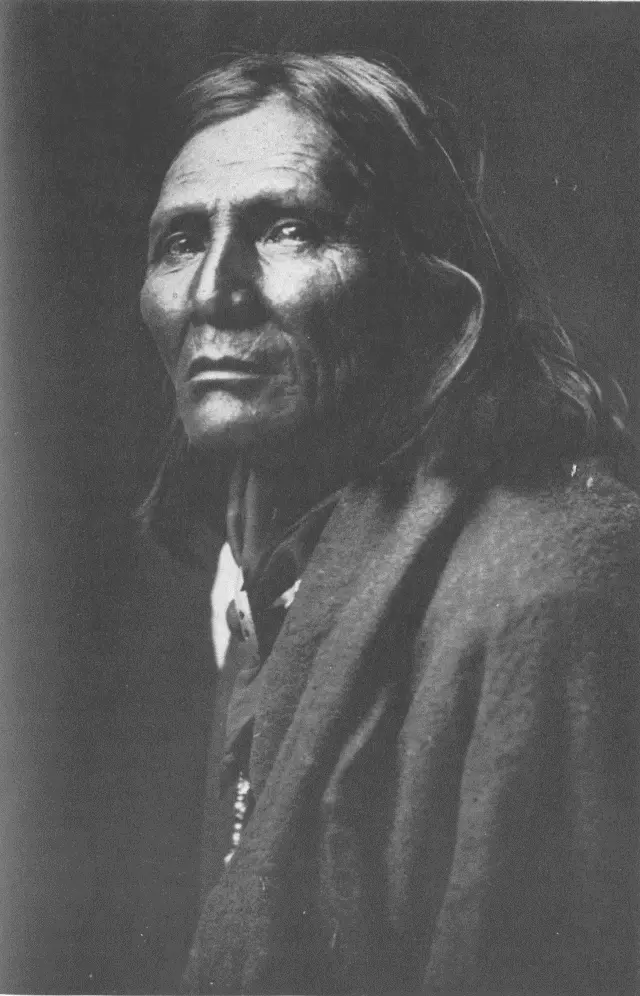

Mescal Hills - Apache

Nabakéltĭ yielded without hesitation to the demands of the soldiers, and forthwith rode up to headquarters. Everything seemed very quiet. There was no demonstration against the soldiers, who stacked their arms and unloaded the pack-trains. The mules were hobbled and turned loose, and the cavalry horses tethered and fed.

While this apparently peaceful condition prevailed, a brother of the medicine-man, angered because of the arrest, dashed into camp on a pony and shot and killed the captain in command. Instantly, hardly realizing whence the shot had come, one of the troopers struck Nabakéltĭ on the head with a cudgel, killing him. Assured that a fight was imminent, the soldiers receded to higher ground, a short distance back, where they hurriedly made preparations for defence.

On learning that Nabakéltĭ had been killed, and deeming the soldiers wholly to blame, a small party of Apache attacked the troopers while retreating to the higher ground. Six of the soldiers were killed, the mules stampeded, and the provisions burned, all within a short space of time. The hostiles made their escape, practically all of them leaving the valley.

The Government probably never lost money faster in an Indian campaign than it did as a result of its interference with Nabakéltĭ's harmless medicine craze. Had he been left alone his inevitable failure, already at hand, to bring the dead to life would have lost him his following, and in all probability his ill-success would have cost his life at the hands of one of his tribesmen. As it was, the hostilities that followed extended over several months, costing many lives and a vast sum of money.

Читать дальше