Names for Indian Tribes—

Apache - Ndĕ (The People)

Arivaipa Apache - Chulĭnné̆

Chiricahua Apache - Aiahán (People of the East)

Coyotero Apache - Klĭnápaha (Many Travel Together)

Havasupai - Dĕzhí̆piklakŭlh (Women Dress in Bark)

Hopi - Tsekŭlkĭnné̆ (Houses on the Rocks)

Navaho - Yutahán (Live Far Up)

Northern Indians - Nda Yutahán (White-man Navaho)

Pima - Saikĭnné̆ (Sand Houses)

Rio Grande Pueblos - Tu Tlú̆nĭ (Much Water)

San Carlos Apache - Tseénlĭn (Between Rocks)

Tonto Apache - Dĭlzhá̆n (Spatter-talkers), or Koún (Rough)

Zuñi - Nashtĭzhé̆ (Blackened Eyebrows)

Infant Burial - Apache

Table of Contents

Language—Athapascan.

Population—784.

Dress—The Jicarillas in dress show the effect of their contact with the Plains tribes, especially the Ute. The primitive dress of the men was a deerskin shirt with sleeves, hip-leggings and moccasins, and the universal loin-cloth. In winter a large loose deerskin coat was worn in addition. The women wore a waist open at the sides under the arms, a deerskin skirt falling below the knees, and legging-moccasins with very high tops. About the waist the women now also wear a very broad leather belt, ten to sixteen inches in width, extending well up under the arms. The men wear their hair in braids hanging over the shoulders and wound with strips of deerskin. Formerly they wore bangs in front on a line with the cheek-bones and tied their hair in a knot at the back of the head, as the Navaho and the Pueblo Indians do. The women part their hair down the middle, bring it to the sides of the head, and tie it with strips of deerskin, cloth, or yarn.

Dwellings—The Jicarilla dwelling is the same as the tipi of the Plains Indians, once made of five buffalo skins on the usual framework of poles, with smoke-hole at the apex. Since the disappearance of the buffalo, canvas has replaced the skins, and many log houses are also to be found on the reservation. The native house is called kozhán.

Primitive Foods—The Jicarillas obtain corn from Rio Grande Pueblos in exchange for baskets; but formerly they subsisted mainly by the chase, killing buffalo, deer, antelope, and mountain sheep, besides many kinds of small game and birds. Piñon nuts and acorns, with various wild fruits and berries, were used. Bear and fish were never eaten.

Arts and Industries—The Jicarillas make a great many baskets of fair quality, from which industry the tribe gained its popular Spanish name. The most typical of their baskets is tray-shaped; this not only enters largely into their domestic life, but was formerly the principal article of barter with their Pueblo neighbors and Navaho kindred. Some pottery is made, practically all of which is in the form of small cooking utensils. The large clay water jar was not used, their wandering life necessitating a water carrier of greater stability.

Organization—While the government of the Jicarillas is very loose, the head-chief, selected from the family of his predecessor, exercises considerable influence. The two bands into which the tribe is divided had their origin when a part of the tribe remained for a period on the plains after an annual buffalo hunt, and henceforth were called Kohlkahín, Plains People; while those who returned to the mountains received the name Sait Ndĕ, Sand People, from the pottery they made. Each of the two bands has a sub-chief. There are no clans.

Marriage—Marriage is consummated only by consent of the girl's parents. The young man proves his worth by bringing to her family a quantity of game, and by building a kozhán, which is consecrated on the night of the wedding, by a medicine-man, with prayers to Nayé̆nayĕzganĭ.

Origin—People, existent with the beginning of time, are guided by Chunnaái, the Sun God, and Klĕnaái, the Moon God, out of an under-world into this, where the various tribes wander about and find their several homes.

Persons of Miraculous Birth—Nayé̆nayĕzganĭ, son of the virgin Yólkai Ĕstsán and the Sun, and Kobadjischínĭ, son of Ĕstsán Nátlĕshĭn and Water, perform many wonders in ridding the earth of its monsters. The former was the more powerful and much mythology centres about him.

Ceremonies—The Girls' Maturity observance, an annual feast whose main features are borrowed from the Pueblos, and a four-days medicine rite are the principal ceremonies of the Jicarillas. Numerous less important medicine chants are held.

Burial—The dead, accompanied with their personal possessions, are taken to elevated places and covered with brush and stones. Their situation is known to only the few who bear the body away. Formerly the favorite horse of the deceased was killed and the kozhán burned, and relatives frequently cut their hair and refrained for a time from personal adornment.

After-world—When the good die their spirits are believed to go to a home of plenty in the sky, where they hunt among great herds of buffalo. Those who have practised "bad medicine," or sorcery, go to another part of the sky and spend eternity in vain effort to dig through the rock into the land of the good.

Names for Indian Tribes—

Apache

Mohave

Yuma

Pima

Chishín (Red Paint)

Comanche

Arapaho

Kiowa and all Plains tribes

Nda (Enemies)

Jicarillas - Haísndayĭn (People Who Came from Below)

Mescaleros - Natahí̆n (Mescal)

Navaho - Inltané̆ (Corn Planters)

Pueblos - Chĭáin (Have Burros)

Ute - Yóta

Table of Contents

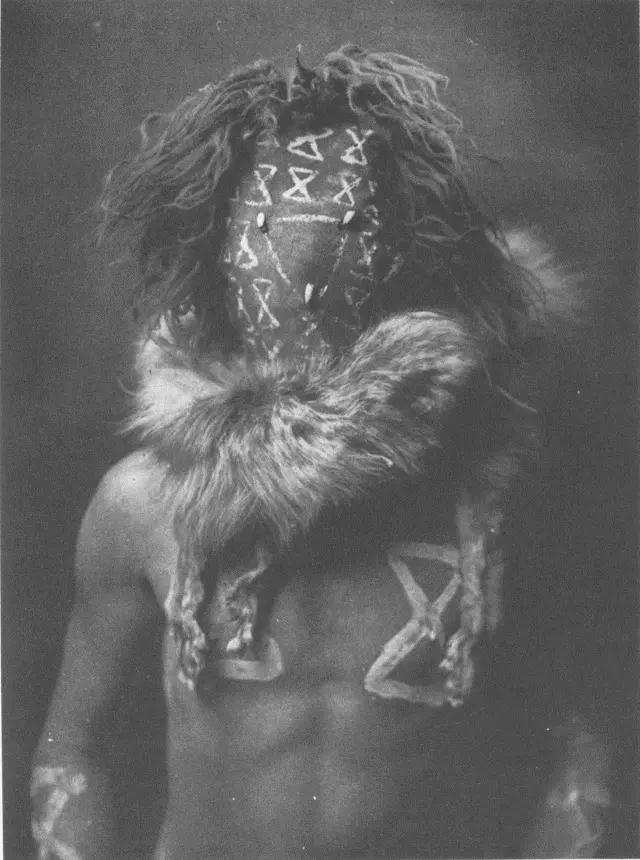

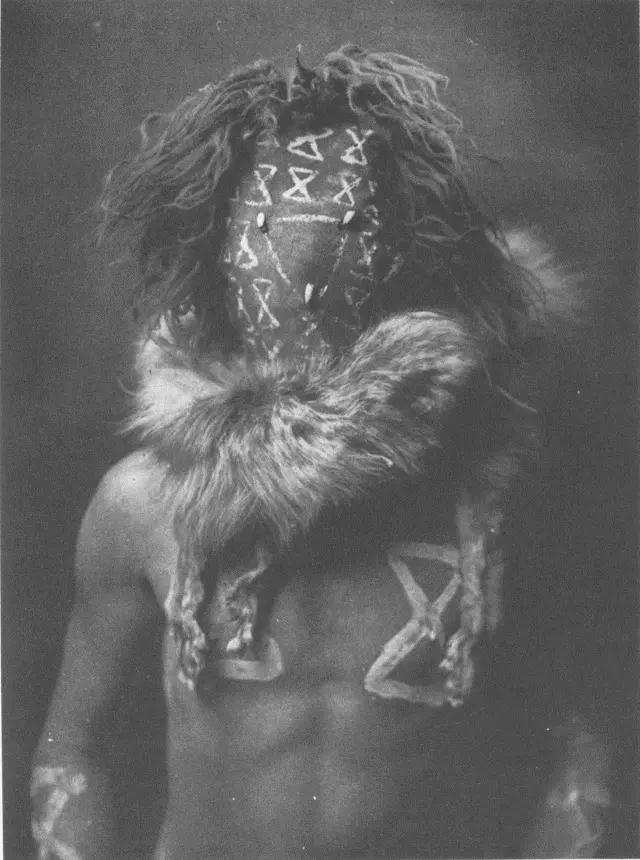

Tobadzĭschí̆nĭ - Navaho

Language—Athapascan.

Population—About 17,000 (officially estimated at 20,600).

Dress—Primitively the men dressed in deerskin shirts, hip-leggings, moccasins, and native blankets. These were superseded by what has been the more universal costume during the present generation: close-fitting cotton or velvet shirt, without collar, cut rather low about the neck and left open under the arms; breeches fashioned from any pleasing, but usually very thin, material, and extending below the knees, being left open at the outer sides from the bottom to a little above the knees; deerskin moccasins with rawhide soles, which come to a little above the ankles, and brown deerskin leggings from moccasin-top to knee, held in place at the knee by a woven garter wound several times around the leg and the end tucked in. The hair is held back from the eyes by a head-band tied in a knot at the back. In early times the women wore deerskin waist, skirt, moccasins, and blanket, but these gradually gave place to the so-called "squaw-dress," woven on the blanket loom, and consisting of two small blankets laced together at the sides, leaving arm-holes, and without being closed at top or bottom. The top then was laced together, leaving an opening for the head, like a poncho. This blanket-dress was of plain dark colors. To-day it has practically disappeared as an article of Navaho costume, the typical "best" dress of the women now consisting of a velvet or other cloth skirt reaching to the ankles, a velvet shirt-like waist cut in practically the same manner as that of the men, and also left open under the arms. Many silver and shell ornaments are worn by both sexes. The women part their hair down the middle and tie it in a knot at the back.

Dwellings—Whatever its form or stability, the Navaho house is called hogán. In its most substantial form it is constructed by first planting four heavy crotch posts in the ground; cross logs are placed in the crotches, and smaller ones are leaned from the ground to these, the corner logs being longer, forming a circular framework, which is covered with brush and a heavy coating of earth. The entrance is invariably at the east. The building of a hogán and its first occupancy are attended with ceremony and prayer. For the great nine-day rites hogáns like those used as dwellings, but larger, are built. Generally they are used for the one occasion only, but in localities where there are very few trees the same ceremonial hogán may be used for a generation or more. For summer use a brush shelter, usually supported by four corner posts and sometimes protected by a windbreak, is invariably used, supplanting a once common single slant shelter.

Читать дальше