Inside the hogán stood four large jewel posts upon which the gods hung their masks. The eastern post was of white shell, the southern of turquoise, the western of abalone, and the northern of jet. Two jewel pipes lay beside a god sitting on the western side of the hogán. These he filled with tobacco and lighted, passing one each to his right and his left. All assembled smoked, the last to receive the pipes being two large Owls sitting one on each side of the entrance way at the east. They drew in deep draughts of smoke and puffed them out violently. While the smoking continued, people came in from all directions. At midnight lightning flashed, followed by heavy thunder and rain, which Tónenĭlĭ, Water Sprinkler, sent in anger because he had not been apprised of the dance before it was time to begin it; but a smoke with the assembled Holy People appeased him. Soon after the chant began and continued until morning.

Some of the gods had beautiful paintings on deerskins, resembling those now made with colored sands. These they unfolded upon the floor of the hogán during the successive days of the hatál.

The last day of the dance was very largely attended, people coming from all holy quarters. Bĭlh Ahatí̆nĭ through it all paid close attention to the songs, prayers, paintings, and dance movements, and the forms of the various sacred paraphernalia, and when the hatál was over he had learned the rite of Kléjĕ Hatál. The gods permitted him to return to his people long enough to perform it over his younger brother and teach him how to conduct it for people afflicted with sickness or evil. This he did, consuming nine days in its performance, after which he again joined the gods at Tsé̆gyiĭ, where he now lives. His younger brother taught the ceremony to his earthly brothers, the Navaho, who yet conduct it under the name of Kléjĕ Hatál, Night Chant, or Yébĭchai Hatál, The Chant of Paternal Gods.

Ceremonies—The Night Chant

Table of Contents

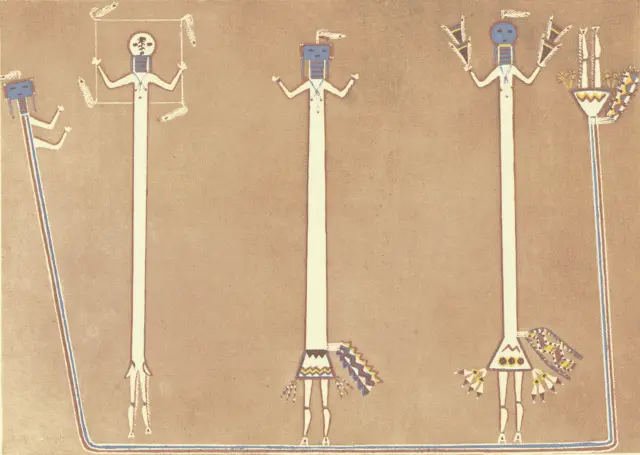

Yébĭchai Sweat - Navaho

Each morning during the first four days of the Navaho Yébĭchai healing ceremony, or Night Chant, the patient is sweated—sometimes inside a small sweat-lodge, oftener by being placed upon a spot previously heated by a fire and covered with heavy blankets. The three figures are medicine-men, or singers, chanting. The patient lies under the blankets surrounded by a line of sacred meal in which turkey-feather prayer-sticks, kĕdán, are implanted.

A description of the ritual and form of the Yébĭchai ceremony,—Kléjĕ Hatál, or Night Chant,—covering its nine days of performance, will give a comprehensive idea of all Navaho nine-day ceremonies, which combine both religious and medical observances. The myth characters personified in this rite are termed Yébĭchai, Grandfather or Paternal Gods. Similar personations appear in other ceremonies, but they figure less prominently.

First Day: The ceremonial, or medicine, hogán is built some days in advance of the rite. The first day's ceremony is brief, with few participants. Well after dark the singer, assisted by two men, makes nine little splint hoops—tsĭpans yázhĕ kĕdán—entwined with slip-cords, and places them on the sacred meal in the meal basket. Following this, three men remove their everyday clothing, take Yébĭchai masks, and leave the hogán. These three masked figures are to represent the gods Hasché̆ltĭ, Talking God, Haschĕbaád, Goddess, and Hasché̆lapai, Gray God. When they have gone and passed to the rear of the hogán, the patient comes in, disrobes at the left of the centre, passes around the small fire burning near the entrance of the hogán, and takes his seat in the centre, immediately after which the singing begins. During the third song Hasché̆ltĭ enters with his cross-sticks—Hasché̆ltĭ balíl—and opens and places them over the patient's body, forcing them down as far toward the ground as possible. The second time he places them not so far over the body; the third, not lower than the shoulders; the fourth time, over the head only, each time giving his peculiar call, Wu-hu-hu-hu-u! Then Hasché̆ltĭ takes up a shell with medicine and with it touches the patient's feet, hands, chest, back, right shoulder, left shoulder, and top of head,—this being the prescribed ceremonial order,—uttering his cry at each placing of the medicine. He next places the shell of medicine to the patient's lips four times and goes out, after which Haschĕbaád comes in, takes one of the circle kĕdán, touches the patient's body in the same ceremonial order, and finally the lips, at the same time giving the slip-cord a quick pull. Next comes Hasché̆lapai, who performs the same incantations with the kĕdán. Again Hasché̆ltĭ enters with the cross-sticks, repeating the former order, after which he gives the patient four swallows of medicine,—a potion different from that first given,—the medicine-man himself drinking what remains in the shell. This closes the ceremony of the first day. There will, perhaps, be considerable dancing outside the hogán, but that is merely practice for the public dance to be given on the ninth night. The singer and the patient sleep in the hogán each night until the nine days are passed, keeping the masks and medicine paraphernalia between them when they sleep.

Second Day: Just at sunrise the patient is given the first ceremonial sweat. This is probably given more as a spiritual purification than in anticipation of any physical benefit. To the east of the hogán a shallow hole is dug in the earth, in which are placed hot embers and ashes,—covered with brush and weeds, and sprinkled with water,—upon which the patient takes his place. He is then well covered with blankets. The medicine-man, assisted by Hasché̆ltĭ and Haschĕbaád, places about the patient a row of feathered kĕdán, and then commences to sing while the patient squirms on the hot, steaming bed. After singing certain songs the medicine-man lifts the blanket a little and gives the patient a drink of medicine from a ceremonial basket. He is again covered, and the singing goes on for a like time. Later the blankets are removed and Hasché̆ltĭ and Haschĕbaád perform over the patient, after which he goes to the hogán. The brush and weeds used for the bed are taken away and earth is scattered over the coals. This sweating, begun on the second day, is repeated each morning for four days: the first, as above noted, taking place east of the hogán, and the others respectively to the south, west, and north. The ceremonies of the second night are practically a repetition of those held the first night. During the third song Hasché̆ltĭ enters with the Hasché̆ltĭ balíl, placing it four times in the prescribed order and giving his call; then he goes out, re-enters, and takes from the medicine basket four sacred reed kĕdán. These he carries in ceremonial order to the four cardinal points: first east, then south, next west, lastly north. Next stick kĕdán are taken out of the basket, which holds twelve each of the four sacred colors. These also are carried to the four cardinal points—white, east; blue, south; yellow, west; black, north. After all the kĕdán are taken out, Hasché̆ltĭ again enters with the Hasché̆ltĭ balíl, using it in directional order and giving medicine as on the night before.

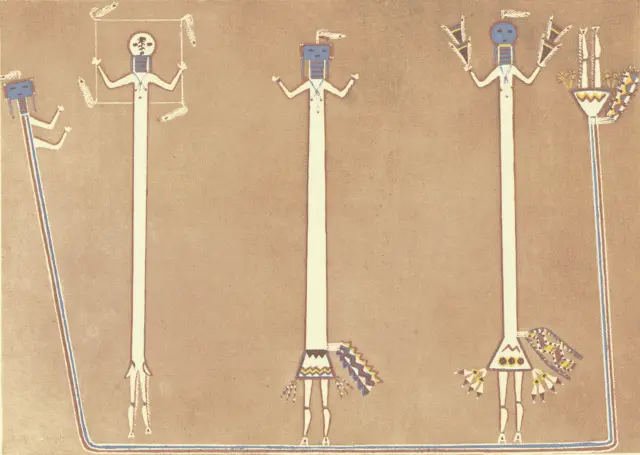

Pĭkéhodĭklad - Navaho

The first of the four dry-paintings used in conducting the Kléjĕ Hatál, or Night Chant, of the Navaho, being made on the fifth night. The purpose of this night's acts is to frighten the patient; hence the name of the painting, which signifies "Frighten Him On It."

Читать дальше