They travelled unimpeded then for quite a long distance, in time coming to four rows of tall, thorny reeds with spiked branches. The reeds grew far enough apart to permit travellers to pass into them, but closed whenever the unwary allowed himself to be caught, and he never escaped. The boys marched boldly up to the reeds and started in, then darted back quickly. The reeds closed instantly, but did not catch them. Then they put the life feathers on their feet again and jumped over all four rows.

The next obstacle was a deep cañon with precipitous walls. This, however, was not a serious impediment, for the life feathers, as before, helped them to cross it in one bound. By nightfall the boys had arrived at a broad, beautiful meadow where lived the Wósakĭdĭ, or Grasshopper People, who received them kindly, giving them food and beds for the night. On being asked whither they were bound, the boys replied that they were journeying to the home of the Sun, their father, whom they had never seen.

The Wósakĭdĭ cautioned the boys of dangers ahead, and as they were about to depart in the morning gave them little balls of yellow sputum to put in their mouths to prevent poisoning, should they find it necessary to eat or smoke among hostile people, and two sacred wands of turquoise and white shell. Two of the Wósakĭdĭ also accompanied them for a time as guides.

They had not been long on their way when they came to a place where the trail ran between two high, smooth-faced bowlders. "These," said their Wósakĭdĭ companions, "are the Bumping Rocks. If you step into that narrow passageway between them they will crash together and kill you." The boys started as if to enter, but fell back. The huge rocks came violently together, but did no harm. The feint was made three times, and each time the rocks crashed together and bounded back. The fourth time the boys entered they placed their sacred wands of turquoise and white shell across the gap above their heads and passed through, for these held the bowlders apart. As they emerged on the opposite side they saw the Sun rising from his eastern home and he was yet far away.

Soon a wide stretch of water was encountered; so far as they could see there was nothing but water. Here again they used their life feathers and were carried safely over. Four successive stretches of water and land were crossed, and still a fifth sheet of water lay before them. Along its shores paddled many varieties of animals. The boys looked out across the deep and could discern away out in the centre a house of turquoise and white shell, its roof glistening in the sunlight. Certain that it must be the home of their father, they readjusted their life feathers to start across, but found that they had lost control over them. They tried them several times in different places, but to no avail. The thought of not reaching their father's house when so near filled their hearts with bitter disappointment. Seemingly there was naught that they could do, but they sat and pondered.

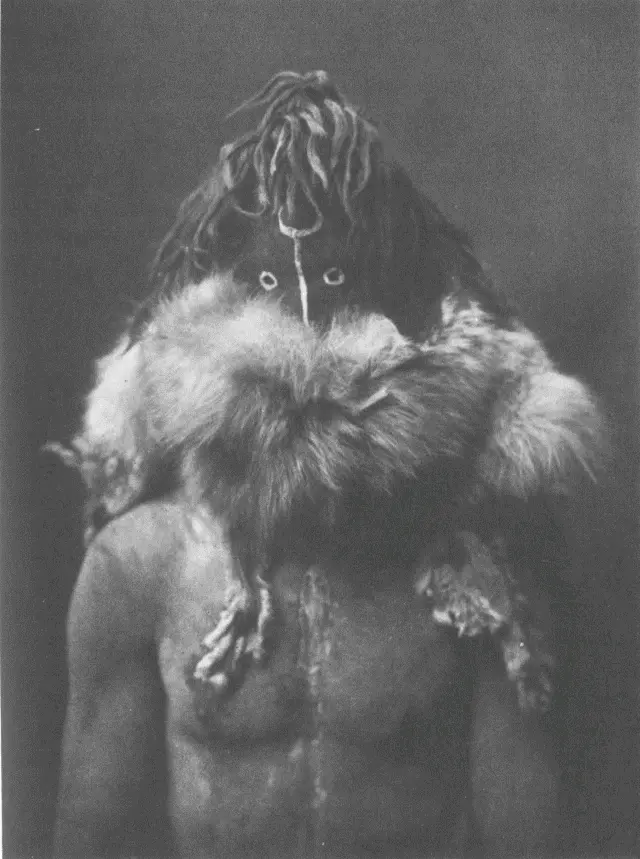

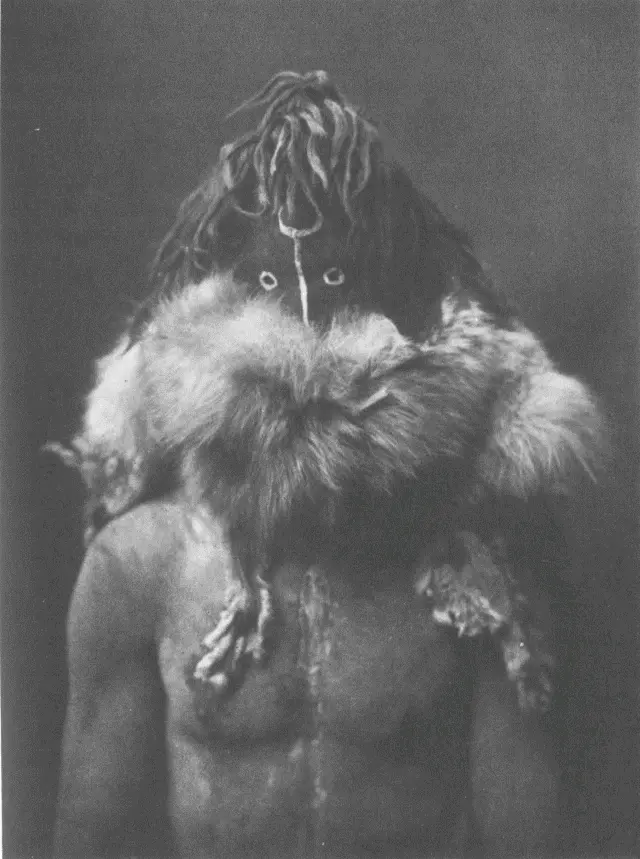

Hasché̆zhĭnĭ - Navaho

Black God, the God of Fire. An important deity of the Navaho, but appearing infrequently in their mythology and ceremonies.

As they sat there in silence, Snipe Man, a little old fellow, came to them and asked, "Where do you go, my grandchildren?"

"To the home of the Sun," the boys replied.

"Do you know anyone there?"

"Yes," said they, "the Sun is our father." Thereupon Snipe Man placed a rainbow bridge across the water and told them to pass on, first warning them against two large Bears, the Lightning, Snakes, and Wind, who guarded the home of the Sun. They crossed over the rainbow bridge, which took them almost to the door of the house, and there they were met by the Bears with bristling coats. Nayé̆nĕzganĭ spoke to them, saying, "I am the child of Yólkai Ĕstsán." They let him pass. Tobadzĭschí̆nĭ uttered the same words and passed on also. The same words took the boys past the Lightning, the Snakes, and the Wind, and they entered the house, going through four doorways before coming to the living-rooms in the interior.

There they found an elderly woman, radiantly beautiful, with two handsome boys and girls, the like of whom they had never seen. They stood transfixed as if in a dream until the voice of the beautiful woman, who was the wife of the Sun, startled them, demanding to know how they dared to enter a sacred place forbidden to all save the Dĭgí̆n.

Nayé̆nĕzganĭ replied, saying, "This is the end of our journey. We came to see our father, the Sun and this we are told is his home."

The wife raged with anger, making dire threats against her husband if what the boys asserted were true, which she did not doubt since they had found it possible to gain entrance to her home. Could it be that he was the father of many of whom she knew nothing? She would find out. Surely he must have smiled upon most ugly creatures if these two boys were his sons!

It was about time for the Sun to return. As his wife thought of what he might do to the boys, her anger turned to compassion, and she bade them wrap themselves in the clouds that hung on the wall, and hide. Ere long a great rattle was heard outside, and a moment later the Sun came striding in and hung up his glistening shield. "What strangers are here?" he asked. There was no answer. Again he asked the question, repeating it a third time and a fourth, waxing angry. Then his wife began to scold. She told him that two boys of his, the ugliest creatures she had ever looked upon, had come to see their father, and demanded to know what it meant. "Where are they?" asked the Sun; but his wife did not reply to the question; instead she kept on scolding. The Sun looked about, and noting a change in the clouds that hung upon the western wall, took them down and unfolded them, until he discovered Nayé̆nĕzganĭ and Tobadzĭschí̆nĭ.

The Sun became angrier than ever and determined to have done with the trouble at once by killing the boys. From the eastern wall of the room projected numerous sharp spikes of white shell. There were turquoise spikes in the southern, abalone in the western, and jet in the northern walls. The boys were each hurled against the first of these, but dropped to the floor unharmed; then against the second, the third, and the fourth, with a like result. On the floor near the walls sat four large mortars with heavy pestles in them. The boys were placed in each of these successively and pounded, as their father thought, into fragments, but out of this also they came unharmed.

The Sun then waved them to a seat and brought forth four large pipes, two of abalone and two of lignite. He handed two of each to the boys, saying, "I wish you to have a good smoke."

"Beware!" whispered the Wind. "His tobacco is poisoned!"

The boys deftly sought the little balls they had received from the Wósakĭdĭ, slipped them into their mouths, and began puffing. When the first pipefuls were finished they laid the pipes on the floor and picked up the other two, showing no sign of distress.

Seeing that the poison tobacco was having no effect on the youthful strangers, the Sun sent for Haschógan and Hasché̆zhĭnĭ, the House God and the Fire God, to come and build a sweat-house and heat large stones as hot as they could be made, so that they might burst into fragments and fill the sweat-lodge with scalding steam when water was poured upon them. By the time the boys had finished their second pipes, which proved as harmless as the others, the little house and heated stones were ready. Haschógan made the lodge of stone and covered it with earth, erecting double walls on the northern side with a space between, into which he provided an entrance from the inside, concealed with a flat stone slab.

Читать дальше