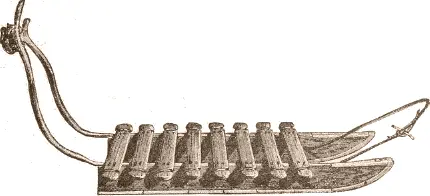

Fig. 477. Eskimo graver’s tool. (National Museum, Washington. 34105.) ½

Ivory implements are cut out of the tusks with strong knives and are shaped by chipping pieces from the blocks until they acquire the desired forms. In olden times it must have been an extremely troublesome work to cut them out, the old knives being very poor and ineffective. They are finished with the file, which on this account is an important tool for the natives; it is also used for sharpening knives and harpoons. The women’s knives are cut, by means of files, from old saw blades; the seal harpoons, from Scotch whale harpoons. If files are not obtainable, whetstones are used for sharpening the iron and stone implements.

Engravings in bone and ivory are made with the implement represented in Fig. 477. An iron point is inserted in a wooden handle; formerly a quartz point was used. The notch which separates the head from the handle serves as a hold for the points of the fingers. The designs are scratched into the ivory with the iron pin.

Stone implements were made of flint, slate, or soapstone. Flint was worked with a squeezing tool, generally made of bone. Small pieces were thus split off until the stone acquired the desired form. Slate was first roughly formed and then finished with the drill and the whetstone. The soft soapstone is now chiseled out with iron tools. If large blocks of soapstone cannot be obtained, fragments are cemented together by means of a mixture of seal’s blood, a kind of clay, and dog’s hair. This is applied to the joint, the vessel being heated over a lamp until the cement is dry. According to Lyon (p. 320) it is fancied that the hair of a bitch would spoil the composition and prevent it from sticking.

Transportation by Boats and Sledges

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

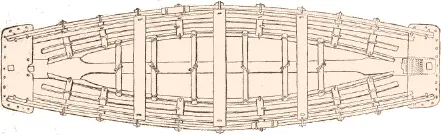

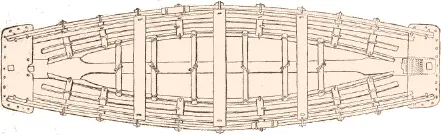

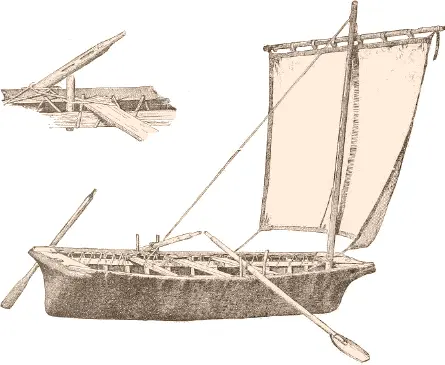

Fig. 478. Framework of Eskimo boat.

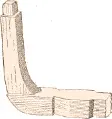

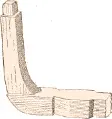

Fig. 479. Kiglo or post.

The main part of the frame of a boat is a timber which runs from stem to stern (Fig. 478). It is the most solid part and is made of driftwood, which is procured in Hudson Strait, Hudson Bay, and on the northern shore of King William Land. In Iglulik, and probably in Pond Bay, boats are rarely used and never made, as wood is wanting. The central part of this timber is made a little narrower than the ends, which form stout heads. A mortise is cut into each of the latter, into which posts (kiglo) are tenoned for the bow and for the stern. The shape of this part will best be seen from the engraving (Fig. 479). A strong piece of wood is fitted to the top of these uprights and the gunwales are fastened to them with heavy thongs. The gunwales and two curved strips of wood (akuk), which run along each side of the bottom of the boat from stem to stern, determine its form. These strips are steadied by from seven to ten cross pieces, which are firmly tied to them and to the central piece. From this pair of strips to the gunwales run a number of ribs, which stand somewhat close together at the bow and the stern, but are separated by intervals of greater distance in the center of the boat. The cross pieces along the bottom are arranged similarly to the ribs. Between the gunwale and the bottom two or three pairs of strips also run along the sides of the boat and steady its whole frame. The uppermost pair (which is called tuving) lies near the gunwale and serves as a fastening for the cover of the boat. The thwarts, three or four in number, are fastened between the gunwale and these lateral strips. All these pieces are tied together with thongs, rivets not being used at all.

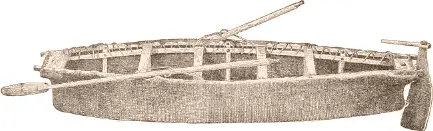

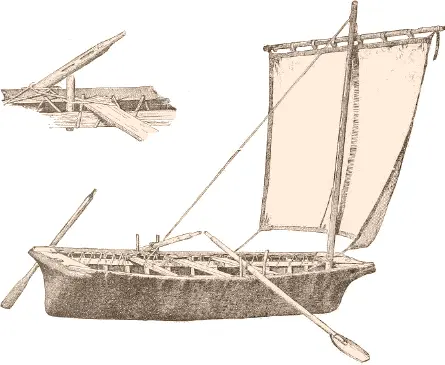

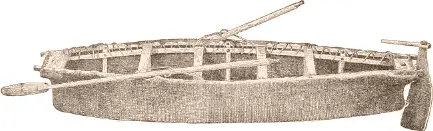

Fig. 480. Umiaq or skin boat.

The frame is covered with skins of ground seals (Figs. 480, 481). It requires three of these skins to cover a medium sized boat; five to cover a large one. If ground seals cannot be procured, skins of harp or small seals are used, as many as twelve of the latter being required. The cover is drawn tightly over the gunwale and, after being wetted, is secured by thongs to the lateral strip which is close to the gunwale. The wooden pieces at both ends are perforated and the thongs for fastening the cover are pulled through these holes.

Fig. 481. Umiaq or skin boat.

The boat is propelled by two large oars. The rowlocks are a very ingenious device. A piece of bone is tied upon the skin in order to protect it from the friction of the oar, which would quickly wear it through (Fig. 481 a ). On each side of the bone a thong is fastened to the tuving, forming a loop. Both loops cross each other like two rings of a chain. The oar is drawn through both loops, which are twisted by toggles until they become tight. Then the toggles are secured between the gunwale and the tuving.

The oar (ipun) consists of a long shaft and an oval or round blade fastened to the shaft by thongs. Two grooves and the tapering end serve for handles in pulling. Generally three or four women work at each oar.

For steering, a paddle is used of the same kind as that used in whaling (see p. 499). A rudder is rarely found (Fig. 480), and when used most probably is made in imitation of European devices.

If the wind permits, a sail is set; but the bulky vessel can only run with the wind. The mast is set in the stem, a mortise being cut in the forehead of the main timber, with a notch in the wooden piece above it to steady it. A stout thong, which passes through two holes on each side of the notch, secures the mast to the wooden head piece. The sail, which is made of seal intestines carefully sewed together, is squared and fastened by loops to a yard (sadniriaq) which is trimmed with straps of deerskin. It is hoisted by a rope made of sealskin and passing over a sheave in the top of the mast. This rope is tied to the thwart farthest abaft, while the sheets are fastened to the foremost one.

Table of Contents

During the greater part of the year the only passable road is that afforded by the ice and snow; therefore sledges (qamuting) of different constructions are used in traveling.

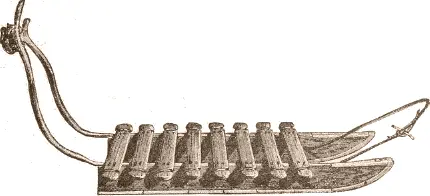

Fig. 482. Qamuting or sledge.

The best model is made by the tribes of Hudson Strait and Davis Strait, for the driftwood which they can obtain in abundance admits the use of long wooden runners. Their sledges (Fig. 482) have two runners, from five to fifteen feet long and from twenty inches to two and a half feet apart. They are connected by cross bars of wood or bone and the back is formed by deer’s antlers with the skull attached. The bottom of the runners (qamun) is curved at the head (uinirn) and cut off at right angles behind. It is shod with whalebone, ivory, or the jawbones of a whale. In long sledges the shoeing (pirqang) is broadest near the head and narrowest behind. This device is very well adapted for sledging in soft snow; for, while the weight of the load is distributed over the entire length of the sledge, the fore part, which is most apt to break through, has a broad face, which presses down the snow and enables the hind part to glide over it without sinking in too deeply.

Читать дальше