Conversation is then diverted to merits or demerits of the Dole--about which Robert feels strongly, and I try to be intelligent but do not bring it off--and difficulty of obtaining satisfactory raspberries from old and inferior canes.

June 12th. --Letter from Angela arrives, expressing rather needless astonishment at recent literary success. Also note from Aunt Gertrude, who says that she has not read my book and does not as a rule care about modern fiction, as nothing is left to the imagination. Personally, am of opinion that this, in Aunt Gertrude's case, is fortunate--but do not, of course, write back and say so.

Cissie Crabbe, on postcard picturing San Francisco--but bearing Norwich postmark as usual--says that a friend has lent her copy of book and she is looking forward to reading it. Most unlike dear Rose, who unhesitatingly spends seven-and-sixpence on acquiring it, in spite of free copy presented to her by myself on day of publication.

Customary communication from Bank, drawing my attention to a state of affairs which is only too well known to me already, enables me to write back in quite unwonted strain of optimism, assuring them that large cheque from publishers is hourly expected. Follow this letter up by much less confidently worded epistle to gentleman who has recently become privileged to act as my Literary Agent, enquiring when I may expect money from publishers, and how much.

Cook sends in a message to say that there has been a misfortune with the chops, and shall she make do with a tin of sardines? Am obliged to agree to this, as only alternative is eggs, which will be required for breakfast. ( Mem. : Enquire into nature of alleged misfortune in the morning.)

( Second, and more straightforward, Mem. : Try not to lie awake cold with apprehension at having to make this enquiry, but remind myself that it is well known that all servants despise mistresses who are afraid of them, and therefore it is better policy to be firm.)

June 14th. --Note curious and rather disturbing tendency of everybody in the neighbourhood to suspect me of Putting Them into a Book. Our Vicar's Wife particularly eloquent about this, and assures me that she recognised every single character in previous literary effort. She adds that she has never had time to write a book herself, but has often thought that she would like to do so. Little things, she says--one here, another there--quaint sayings such as she hears every day of her life as she pops round the parish--Cranford, she adds in conclusion. I say Yes indeed, being unable to think of anything else, and we part.

Later on, our Vicar tells me that he, likewise, has never had time to write a book, but that if he did so, and put down some of his personal experiences, no one would ever believe them to be true. Truth, says our Vicar, is stranger than fiction.

Very singular speculations thus given rise to, as to nature of incredible experiences undergone by our Vicar. Can he have been involved in long-ago crime passionnel , or taken part in a duel in distant student days when sent to acquire German at Heidelberg? Imagination, always so far in advance of reason, or even propriety, carries me to further lengths, and obliges me to go upstairs and count laundry in order to change current of ideas.

Vicky meets me on the stairs and says with no preliminary Please can she go to school. Am unable to say either Yes or No at this short notice, and merely look at her in silence. She adds a brief statement to the effect that Robin went to school when he was her age, and then continues on her way downstairs, singing something of which the words are inaudible, and the tune unrecognisable, but which I have inward conviction that I should think entirely unsuitable.

Am much exercised regarding question of school, and feel that as convinced feminist it is my duty to take seriously into consideration argument quoted above.

June 15th. --Cheque arrives from publishers, via Literary Agent, who says that further instalment will follow in December. Wildest hopes exceeded, and I write acknowledgment to Literary Agent in terms of hysterical gratification that I am subsequently obliged to modify, as being undignified. Robert and I spend pleasant evening discussing relative merits of Rolls-Royce, electric light, and journey to the South of Spain--this last suggestion not favoured by Robert--but eventually decide to pay bills and Do Something about the Mortgage. Robert handsomely adds that I had better spend some of the money on myself, and what about a pearl necklace? I say Yes, to show that I am touched by his thoughtfulness, but do not commit myself to pearl necklace. Should like to suggest very small flat in London, but violent and inexplicable inhibition intervenes, and find myself quite unable to utter the words. Go to bed with flat still unmentioned, but register cast-iron resolution, whilst brushing my hair, to make early appointment in London for new permanent wave.

Also think over question of school for Vicky very seriously, and find myself coming to at least three definite conclusions, all diametrically opposed to one another.

June 16th. --Singular letter from entire stranger enquires whether I am aware that the doors of every decent home will henceforward be shut to me? Publications such as mine, he says, are harmful to art and morality alike. Should like to have this elucidated further, but signature illegible, and address highly improbable, so nothing can be done. Have recourse to waste-paper basket in absence of fires, but afterwards feel that servants or children may decipher fragments, so remove them again and ignite small private bonfire, with great difficulty, on garden path.

( N.B. Marked difference between real life and fiction again exemplified here. Quite massive documents, in books, invariably catch fire on slightest provocation, and are instantly reduced to ashes.)

Question of school for Vicky recrudesces with immense violence, and Mademoiselle weeps on the sofa and says that she will neither eat nor drink until this is decided. I say that I think this resolution unreasonable, and suggest Horlick's Malted Milk, to which Mademoiselle replies Ah, ça, jamais ! and we get no further. Vicky remains unmoved throughout, and spends much time with Cook and Helen Wills. I appeal to Robert, who eventually--after long silence--says, Do as I think best.

Write and put case before Rose, as being Vicky's godmother and person of impartial views. Extreme tension meanwhile prevails in the house, and Mademoiselle continues to refuse food. Cook says darkly that it's well known as foreigners have no powers of resistance, and go to pieces-like all in a moment. Mademoiselle does not, however, go to pieces, but instead writes phenomenal number of letters, all in purple ink, which runs all over the paper whenever she cries.

I walk to the village for no other purpose than to get out of the house, which now appears to me intolerable, and am asked at the Post Office if it's really true that Miss Vicky is to be sent away, she seems such a baby. Make evasive and unhappy reply, and buy stamps. Take the longest way home, and meet three people, one of whom asks compassionately how the foreign lady is. Both the other two content themselves with being sorry to hear that we're losing Miss Vicky.

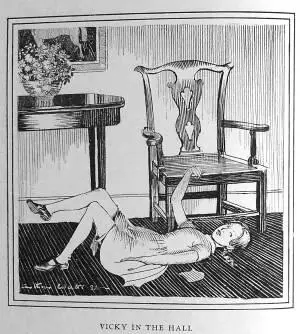

Crawl indoors, enveloped in guilt, and am severely startled by seeing Vicky, whom I have been thinking of as a moribund exile, looking blooming, lying flat on her back in the hall eating peppermints. She says in a detached way that she needs a new sponge, and we separate without further conversation.

Читать дальше