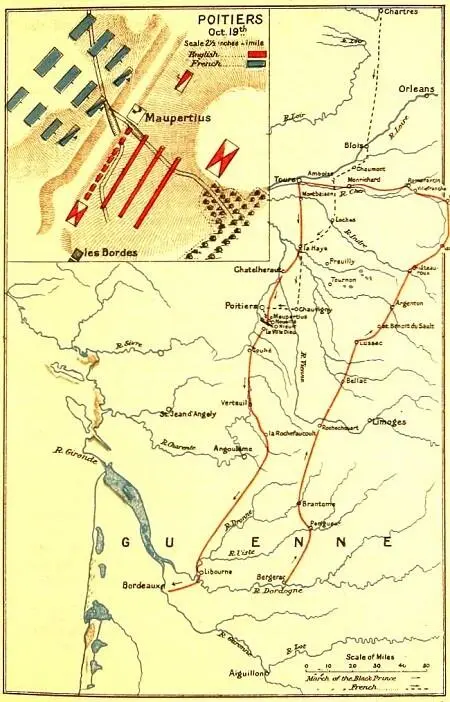

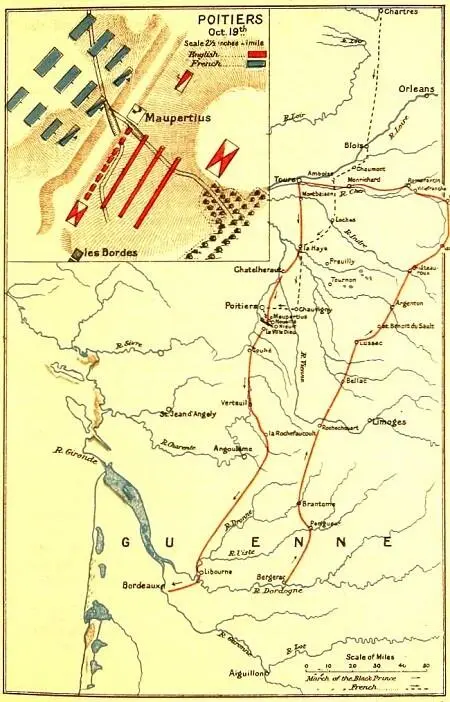

There was now nothing for the Prince but to retire southward with all haste. The French were hard on his track, and followed him so closely that he was much straitened by want of supplies. On the 14th of September the English were at Chatelheraut and the French at La Haye, little more than ten miles apart, and on the 15th the French made a forced march which brought them fairly to southward of the Prince, and between him and his base at Bordeaux. All contact however had been lost; and the French King, making sure that the Prince had designs on Poitiers, swung round to the westward and moved straight upon the town. On the 17th, while in full march, his rearguard was suddenly surprised by the advanced parties of the Prince. As in the movements after the Alma, each army was executing a flank march, quite unconsciously, in the presence of the other. The French rearguard pursued the reconnoitring party to the main body of the English, and after a sharp engagement was repulsed with heavy loss. The French army had actually marched across the line of the Black Prince's retreat, and left it open to him once more.

Sept. 18.

Edward lost no time in looking for a suitable position, and presently found it at Maupertuis some fifteen miles south-west of Poitiers. There to the north of the river Miosson is a plain seamed with deep ravines running down to that stream; and behind one of these he took his stand, facing north-east. The sides of the ravine were planted with vineyards and blocked by thick hedges, so that it was impossible for cavalry to cross it except by a track which was broad enough for but four horsemen abreast; and these natural advantages the Prince improved by repairing all weak places in the fences and by digging entrenchments. One exposed spot on his left flank he strengthened by a leaguer of waggons as well as with the spade. He then told off his archers to line the hedges which commanded the passage across the ravine, and drew up his men-at-arms, all of them dismounted, in three lines behind it. The first line he committed to the Earls of Warwick and Suffolk, the rearmost to the Earl of Salisbury, and the centre he reserved for himself. His whole force, augmented as it was by a contingent of Gascons, did not exceed six or seven thousand men, half of whom were archers.

So passed the day of the 18th of September on the English side. The French on their part, instead of blocking up their retreat to the south and reducing them by starvation, simply moved down from Poitiers to within a league of the English position and halted for the night. Their force amounted to sixty thousand men, and they might well feel confident as to the issue of an action. Indeed, when the Black Prince, fully alive to the desperate peril of his situation, negotiated for an evacuation of the country, they imposed such terms that he could not in honour accept them. They therefore reconnoitred the English position, and laid their plans for the morrow. Three hundred chosen men-at-arms, backed by a column of German, Italian, and Spanish knights, were to charge down the ravine upon the archers, disperse them, and attack the English men-at-arms on the other side. Three lines, each of three massive battalions containing from three to four thousand men-at-arms, with lances shortened to a length of five feet, were to follow them afoot, and the English were to be crushed by their own tactics.

Sept. 19.

It is hardly surprising that in the night the Black Prince's heart failed him. He resolved while he could to place the Miosson between him and the French, and at dawn began his retreat, leaving the rearguard, however, still in the position at Maupertuis in case withdrawal should be impossible.[24] He also sent two knights to watch the French army, who however approached too closely to it and were captured. His first line had already crossed the Miosson when intelligence reached him that the French had advanced, and that the rearguard was engaged. He at once ordered the vanguard to return, and himself hastening back with his own division, despatched three hundred mounted men-at-arms and as many mounted archers without delay to strengthen his right wing. The French meanwhile had moved forward, gaily singing the song of Roland, to find the way blocked by the hedges and vineyards of the ravine. Undismayed they plunged down into the narrow track; and then the English archers behind the hedges opened at close range a succession of frightfully destructive volleys. The foremost of the horsemen fell headlong down, the rear plunged confusedly on the top of them, and the pass was blocked with a heaving, helpless crowd, on which the arrows hissed down in an eternal merciless shower. The supporting column of foreign cavalry was unable to act in the confusion; it was already under the fire of the archers, and before it could move the English mounted men on the right wing came down full upon its left flank, and killed or captured every man.

THE CAMPAIGN OF 1356.

And now the wounded French horses, mad with pain and terror, many of them riderless and all beyond control, dashed back on to the first line of the dismounted French men-at-arms. It was a charge of mad animals, the most terrible of all charges, and the huge battalion fell into confusion before it. Edward was watching the battle keenly from his position; he had already ordered his men-at-arms to mount, and now Sir John Chandos, whose name must always be linked to Edward's as that of Collingwood to Nelson, broke out aloud with, "Forward, sire, forward, and the day is yours!" "Aye, John," answered the Prince, with a thought perhaps of the morning's retreat, "No going backward to-day. Forward banner, in the name of God and St. George!" The preliminary attack of the mounted men on the right had already cleared the way for them. The English cavalry scrambled in haste down into the ravine on the right, and fell upon the French men-at-arms. The front and centre divisions, already much shaken, were easily broken and dispersed; the third and strongest still remained, and against this, which resisted desperately, the whole force of the English was turned. The lesson of Falkirk was remembered. The mounted archers made the gaps and the men-at-arms rode into them. The division was broken, the King was captured, and the mass of the fugitives making for Poitiers found the gates closed against them and were cut down by hundreds. The action began at six in the morning, and lasted till late into the afternoon. The French losses were enormous. Over and above the King and many great lords two thousand men-at-arms were captured, and two thousand five hundred more were left dead on the field; the number of the unhappy foot-men that were slain it is impossible to state. The English loss is variously set down, the reports ranging from half the force to sixty-four men. The battle, from the disparity between the strength of the two sides, must remain ever memorable in the annals of war. To the English, who had but lately risen above the horizon as a military power, it gave a prestige that has never been lost.

1360.

1364,

May 16.

The peace of Brétigny closed the war, and the English army was disbanded. But the soldiers, like the ten thousand Greeks who returned from Cunaxa, were too deeply bitten with their profession to abandon it for the tedium of peace. They therefore formed themselves into independent bodies, or Free Companies, and for years were the scourge of France, their chamber as they called it, which they plundered and ravaged at their pleasure. The greatest of their leaders was John Hawkwood, of whom something more must presently be said, but these bands, in less or greater numbers, were constantly to be found fighting for hire against the French. Thus three hundred of them fought for the King of Navarre against the King of France at Cocherel. The numbers engaged were little more than fifteen hundred on each side, but the action is interesting as showing the efforts of the French to meet the peculiar tactics of the English. In order to have no more trouble with unruly horses the French men-at-arms dismounted and fought on foot, and now for the first time the archers found themselves outdone. The armour of the French was so good that it turned the cloth-yard shafts; and being slightly superior in numbers the French men-at-arms forced their enemy off the field. It was but a slight success, but a defeat even of a small body of English was such a rarity in those days that it gave the French great hopes for the future, hopes which were soon to be dashed to the ground.

Читать дальше