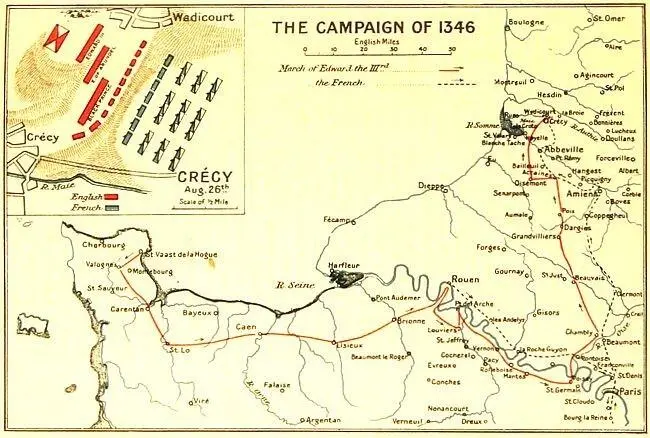

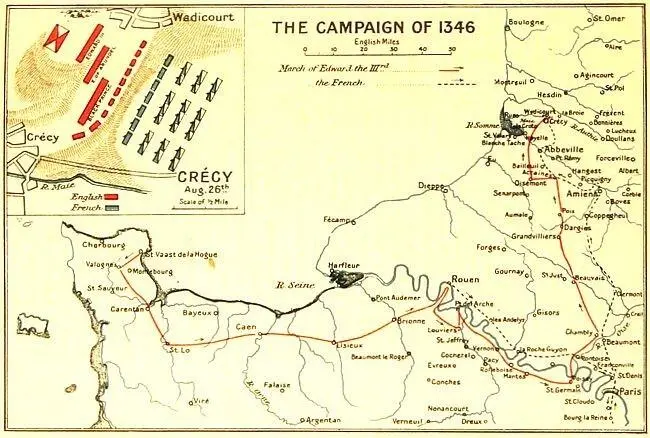

August 26.

The position was well chosen. The army occupied a low line of heights lying between the villages of Creçy and Wadicourt, the left flank resting on a forest, the right on the river Maie. Edward ordered every man to dismount, and parked the horses and baggage waggons in an entrenched leaguer[23] in rear. The army was too weak to cover the whole line of the position, so the archers were pushed forward and extended in a multitude of battalions along the front, and backed with Welsh spearmen. Echeloned in rear of them stood the three main divisions of the army; foremost and to the right the vanguard of twelve hundred men-at-arms under the Black Prince, next to it the battle of as many more under the Earl of Arundel, and behind it, covering the extreme left, the rearguard, consisting of fifteen hundred men-at-arms and six thousand mixed archers and infantry under the King. The country being rich in provisions Edward ordered every man to eat a hearty meal before falling into his place, for he knew that the Englishman fights best when he is full. When the host was arrayed in order he rode round the whole army to cheer it; and then the men lay down, the archers with their helmets and bows on the ground before them, and waited till the French should come.

Philip meanwhile had crossed the Somme at Abbeville on the morning of the 26th, and turned eastward in the hope of cutting off the English. Finding that he was too late, he countermarched and turned north, at the same time sending forward officers to reconnoitre. The afternoon was far advanced, and the French were wearied with a long, disorderly march when these officers returned with intelligence of the English. Philip ordered a halt, but the indiscipline and confusion were such that the order could not be obeyed. The noblest blood in France was riding on in all its pride to make an end of the despised English, and a mass of rude infantry was waiting to share the slaughter and the spoil. So they blundered on till they caught sight of the English lying quietly down in order of battle; and therewith all good resolutions vanished and Philip gave the order to attack.

It was now nearly five o'clock, and the heaven was black with clouds, which presently burst in a terrific thunderstorm. The English archers slipped off their bowstrings to keep them dry, and waited; while six thousand Genoese cross-bowmen, jaded by the long march, drenched and draggled with the rain that beat into their faces, conscious that they were almost disarmed by the wetness of their bowstrings, shuffled wearily into their stations along the French front. Their leaders complained that they were unfairly treated. "Who cares for your rabble?" answered the Count of Alençon. "They are nothing but useless mouths, more trouble than help." So the cross-bowmen sulkily took their position, and the rest of the French army, from twelve to twenty thousand men-at-arms and some fifteen thousand infantry, ranged themselves in three massive lines behind them. A vast flight of ravens flew over the opposing arrays, croaking loudly over the promised feast of dead men.

Then the storm passed away inland into France, and the sun low down in the west flashed out in all his glory full in the faces of the French. The Genoese advanced and raised a loud cry, thrice repeated, to strike terror into the English: the archers over against them stood massive and silent. The loud report of two or three cannon, little more harmful than the shouts of the Genoese, was the only answer; and then the archers stepped forward and drew bow. In vain the Genoese attempted to reply; they were overwhelmed by the torrent of shafts; they shrank back, cut their bowstrings and would have fled, but for a line of French mounted men-at-arms which was drawn up in their rear to check them. The proud chivalry of France was chafing impatiently behind them, and Philip would wait no longer. "Slay me these rascals," he said brutally; and the first line of men-at-arms thundered forward, trod the hapless Genoese under foot, and pressed on within range of the arrows. And then ensued a terrible scene. The great stallions, maddened by the pain of the keen barbed shafts, broke from all control. They jibbed, they reared, they swerved, they plunged, striking and lashing out hideously, while the rear of the dense column, carried forward by its own momentum, surged on to the top of the foremost and wedged the whole into a helpless choking mass. And still the shower of pitiless arrows fell swift as snow upon the thickest of the press; and the whole of the French fighting line became a confused welter of struggling animals, maimed cross-bowmen, and fallen cavaliers, crippled by the weight of their armour, an easy prey to the long, keen knives of the Welsh.

THE CAMPAIGN OF 1346.

Nevertheless some few of the French men-at-arms had managed to pierce through the archers. The blind king of Bohemia had been guided by two faithful knights through the centre, Alençon had skirted them on one flank, the Count of Flanders on the other, and all had fallen upon the Black Prince's battalion. The danger was greatest on the left flank; but the Earl of Arundel moved up the second line of the echelon to his support, and the English held their own. Then the second line of the French advanced, broke through the archers, not without heavy loss, and fell likewise upon the English men-at-arms. The Prince of Wales was overthrown, and was only saved by the devotion of his standard-bearer, but the battalion fought on. It was probably at this time that Arundel sent a messenger to the King for reinforcements. "Is my son dead or hurt?" he asked. "No, sire, but he is hard beset." "Then return to those who sent you and bid them send me no more such messages while my son is alive; tell them to let the boy win his spurs." The message was carried back to the battalion, and the men-at-arms fought on stoutly as ever. The archers seem also to have rallied and closed on the flank and rear of the attacking French. Alençon's banner could still be seen swaying behind a hedge of archers, and Philip, anxious to pour his third and last line into the fight, had actually advanced within range of the arrows. But the power of the bowmen was still unweakened, the ground was choked with dead men and horses, and the light was failing fast. He yielded to the entreaties of his followers and rode from the field; and the first great battle of the English was won.

When morning dawned the country was full of straggling Frenchmen, who from the sudden change in the direction of the advance had lost all knowledge of their line of retreat; the few that retained some semblance of organised bodies were attacked and broken up. Never was victory more complete. The French left eleven great lords, eighty-three bannerets, over twelve hundred knights and some thousands of common soldiers dead on the field. It was a fortunate issue to a reckless and ill-planned campaign. It is customary to give all credit for the victory to the archers, but this is unjust. Superbly as they fought they would have been broken without the men-at-arms, even as the men-at-arms would have been overwhelmed without the archers. Both did their duty without envy or jealousy, and therein lay the secret of their success.

1355.

1356.

July.

August 28.

The siege and capture of Calais followed, and then by the mediation of the Pope peace was made, and for a time preserved. Petty hostilities however never ceased in Brittany, and finally in 1355 the war broke out anew. Three armies were fitted out—one of a thousand men-at-arms under the Black Prince for operations in Guienne, a second under the Earl of Derby for Brittany, and a third under the personal command of the King. Little, however, was effected in the campaign of 1355. The King was recalled to England by an invasion of the Scots, and the operations of 1356 in Brittany were checked by the appearance of the French King in superior force. But at the close of July the Black Prince suddenly started on a wild raid from the Dordogne in the south to the Loire. His object seems to have been to effect a junction with Derby's forces at Orleans; but it is difficult to see how he could have hoped for success. He had reached Vierzon on the Cher when he heard that the King of France was on his way to meet him in overwhelming strength. Unable to retreat through the country which he had laid waste on his advance, he turned sharp to the west down the Cher and struck the Loire at Tours. There for four days he halted, for what reason it is difficult to explain, since the delay enabled the French to cross the Loire and seriously to threaten his retreat.

Читать дальше