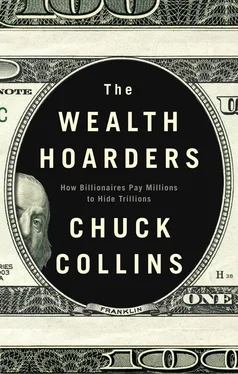

I raise my hand. “I know everyone says that you should never give away your principal.” [This is the asset foundation of one’s wealth that generates income.] “But why not?” I say. “I’ve been wrestling with the ethics of continuing to hold onto wealth. Would anyone else like to talk about giving away assets?” The question hangs in the air for a moment.

“I would,” volunteers Edorah, smiling warmly from across the room. The two of us had already spent most of the previous evening talking about the idea.

“That would be …” flutters an older woman named Dee, craning forward in her chair. “That would be utterly foolish.”

“Yes,” agrees Catherine, a friend of Dee. “Don’t ever touch the principal.”

“Hold your horses,” Melanie interjects with a chairwoman’s authority. “They can talk about whatever they want. Are there others that want to join Chuck and Edorah?”

Two others raise their hands, and we are assigned a meeting room. Dee and Catherine join our group of four in order to convince us we are loony. “We are both grandmothers,” Dee explains. “We know a thing or two.”

“What will you prove by committing class suicide ?” asks Catherine. Her face is flushed and agitated – and she eyes me through her thick glasses as if I am about to detonate a bomb.

“Give away your income,” counsels Dee more calmly. “But for God’s sake, don’t touch the principal.” Her silvery blond hair is pulled back in a bun and she flashes beautiful white teeth. Dee is from a well-known New England family and can attest to the benefits of holding onto money through multiple generations. 1

Catherine and Dee dominate the conversation with stories of imprudent cousins who “invaded their principal” with “hare-brained” investment and charitable schemes. One of Catherine’s cousins had been duped into signing over part of a trust to a religious cult. “Don’t do anything foolish today that you’ll regret tomorrow,” they repeat like a Greek chorus.

A few days after the conference, Dee “rings me up,” as she says, and invites me to lunch at the Harvard Club on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston. I am planning to be in Boston on business and eagerly agree. I appreciate that Dee is interested in my dilemma, even if she disagrees with me. For years I have been simmering inside about having wealth, but I’ve had few chances to talk with others who have both money and a sense of responsibility about what to do with it. Dee is a full-time philanthropist, and a woman who has wrestled with privilege for six decades and made seemingly thoughtful choices. I wonder if her path holds any guidance for me.

I have never been to the Harvard Club. I iron a shirt, fuss over my tie and walk down the broad boulevard of Commonwealth Avenue in Boston’s Back Bay, where the median is lined with sculptures of literary figures and political leaders. On each side are four- and five-story homes, granite slab and brick behemoths with large picture windows and ivy. Some are divided into apartment buildings or condominiums, but many are still occupied by single families. Approaching the Harvard Club reminds me of another important aphorism of privilege – along with “never touch the principal” – which is, “always look like you belong.” I stride confidently past the large awning and doorman at the Harvard Club.

I meet Dee in the club lounge. She strides in, hair long, shoulder bag swinging. She is wearing a crisp knee-length black skirt and a breezy white blouse with a golden basket lapel pin that she explains is a symbol of Nantucket Island, where she has a “cottage.” The lounge is remarkably free of cigar smoke and captains of industry. There are several low-rise chairs and fairly ordinary people – men not even wearing ties – sitting and reading newspapers.

“Dee,” I whisper, “Where are the Monopoly Man plutocrats and the wingback chairs?”

“Oh yes,” she deadpans. “They are in the gentlemen’s smoking lounge pulling the hidden levers of power. They don’t allow the ladies in there.” We enter the dining room, and Dee waves to several other women she knows. “I have to tell you a joke,” she says, glancing up from her menu with a puckish grin. Her face is tanned and freckled since I’d seen her a few weeks earlier.

Dusk is settling in over the Charles River, and a proper Boston gentleman is walking home from his day’s duty at the Brahmin law firm of Prescott, Cabot, and Newell. As he climbs Beacon Hill toward his stately red brick row house, he spies a lady of the night, standing in a shadowy doorway. As he passes, he averts his eyes, but not before recognizing his dearest first cousin.

“Addy,” he stutters. “Addy, is it you?”

“Yes Arthur,” she whispers with shame.

“But Addy … why? Why you?”

“Why, Arthur,” his cousin responds. “It was either this or invade the principal.”

We both roar with laughter. Dee is right about one thing. I am naive about “principal,” “assets,” “income,” and “inherited legacies.” But Dee is prying my eyes open to the world of wealth preservation. “Chuck, you can do a lot of good if you hold onto the money.” Dee smiles. “As the corpus grows, you have more income that you can give away.”

“Corpus?” I am stuck on the word.

“You know … the body … the principal.”

“I can’t help interrupting, but that word,” I shake my head. “When I hear ‘Corpus’ I think of ‘Corpus Christi’.”

“Yes, of course,” chuckles Dee. “The body of Christ. Like the little wafer I palm once a week down at old Trinity Church.” I know that Dee is a member of Trinity Church and serves on several church committees. But she is no stuffy WASP former debutante.

“I understand the theory,” I continue. “The principal is thy fount. It is the gift that keeps giving. It is the goose that lays the golden egg. You don’t barbecue the goose.”

Dee looks at me with a mix of bemusement and sadness. “What’s wrong with preserving an asset?” Where do I begin? I think. I picture my older friend Juanita Nelson standing in her two-room cabin talking about usury and the immorality of people with mountains of wealth living off interest. Where did that income come from?

I think about the Bernardston mobile home tenants and other low-income people I work with, who take second jobs to pay the high interest rates on their homes. I want to draw their voices into the conversation.

“I don’t want to live off other people’s labor.”

“Oh Chuck, people need access to credit,” Dee says, missing my point. “Borrowing and interest are what makes the world go around.”

“Not the world I want to live in.” I start to talk about my views on wealth and poverty in society, but Dee steers the conversation back to the personal.

“Do you feel bad about having money?” she asks.

“Well, maybe, because I had nothing to do with earning it.”

“Guilt is a dead end,” she nods with certainty.

“Dee, isn’t there a part of guilt that is okay, that’s sort of a sign of our humanness?” I am struggling for the right words. “Maybe guilt is the wrong word, but don’t you feel something when you see the distance between your own good fortune and the suffering of others?”

“There is nothing good about guilt,” she pronounces, skating past my words. I sense this is in the pantheon of rich people’s aphorisms along with “never touch the principal” and “if you have to ask ‘how much?’ you can’t afford it.”

“But what about being … responsible?”

“Well, of course, I believe in responsibility, but Chuck, do you feel responsible for all the world’s suffering?” I hear slight mocking in her question, in a way I’ve heard people dismiss those who “want to change the world.”

Читать дальше