1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...29 As Lewis (2006, p. 195) states:

Humans moved more rock, sediment and soil than all natural processes combined, by an order of magnitude … Between a third and half of all land was appropriated for human use … By the [21st] century’s end three to six times as much water was held in reservoirs as in natural rivers … Two predictions stand out: changes in land‐use will cause the sixth mass extinction in evolutionary history … while atmospheric CO 2concentrations will reach their highest levels for 60 million years.

The human footprint on Earth is already very deep, and each year that passes without significant reversal of course will make our presence an ever‐greater disrupter of Earth ecological, climatic, atmospheric, hydraulic, and other systems. As Vitousek et al . (1997, p. 494) observe, “[u]ntil recently, the term ‘human‐dominated ecosystems’ would have elicited images of agricultural fields, pastures, or urban landscapes; now it applies with greater or lesser force to all of Earth.” Quite literally no location on the planet is totally untouched by our species. One place you would not expect to find a human footprint is at the bottom of the ocean. While our knowledge about the complexities and lifeforms of the deep ocean (below 10 000 feet) remains limited, of one thing we are certain: human activities are increasingly affecting deep‐sea habitats. This is the conclusion of an international study conducted by over 20 deep‐sea scientific experts who participated in the Census of Marine Life project SYNDEEP (Towards a First Global Synthesis of Biodiversity, Biogeography, and Ecosystem Function in the Deep Sea). They grouped the impacts they detected into three types: waste and litter dumping, resource exploitation, and evidence of the effects of climate change (Ramirez‐Llodra et al . 2011).

The routine dumping of many types of waste from ocean‐going ships was legally banned by the London Convention of 1972. An even stricter convention went into force in 2006. Before these bans, a wide array of human litter regularly was dumped from ships, large and small, in ocean transit. New litter continues to accumulate as a result of illegal disposal, lost or discarded fishing gear, and being washed from the coast and through river discharges. It is estimated that 6.4 million tons of litter is deposited into the oceans each year, part of which sinks to the deep ocean bottom (Jeftic et al . 2009). In places like the Mediterranean and North East Atlantic, the most common litter types found on the deep ocean floor are soft plastic (e.g., bags), hard plastic (e.g., bottles, containers), and glass and metal (e.g., cans) (Galil et al . 1995; Galgani et al . 2000).

Expanding technological capabilities have facilitated the exploitation of biological, mineral, and petrochemical resources from the oceans. Trawl fishing can reduce the biodiversity and biomass of deep‐water invertebrates, such as cold‐water corals, with long‐term effects persisting even after fishing has ended. Deep ocean mining is also of increasing concern. Three forms of mineral resources have been identified for commercial exploitation: manganese nodule mining on deep ocean plains, cobalt‐rich crusts on seamounts, and polymetallic sulfide deposits at sites of hydrothermal vents. An additional threat is ultra‐deep‐water oil and gas drilling, the potential adverse consequences of which were exposed by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico (Michel et al . 2013).

Rising levels of anthropogenic (human‐generated) greenhouse gases have made parts of the North Atlantic and hot spots in the Northern Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans so acidic that the chalky white form of calcium carbonate known as calcite that makes up the seafloor is dissolving. This dissolution is “altering the geological record of the deep sea” (Sulpis et al . 2018, p. 11 700). Moreover, in the European sector of the North East Atlantic, the extent of the effects of bottom trawling by fishing boats is significant—an order of magnitude greater than the total impact of all other activities (e.g., waste disposal, telecommunication cables) (Benn et al . 2010).

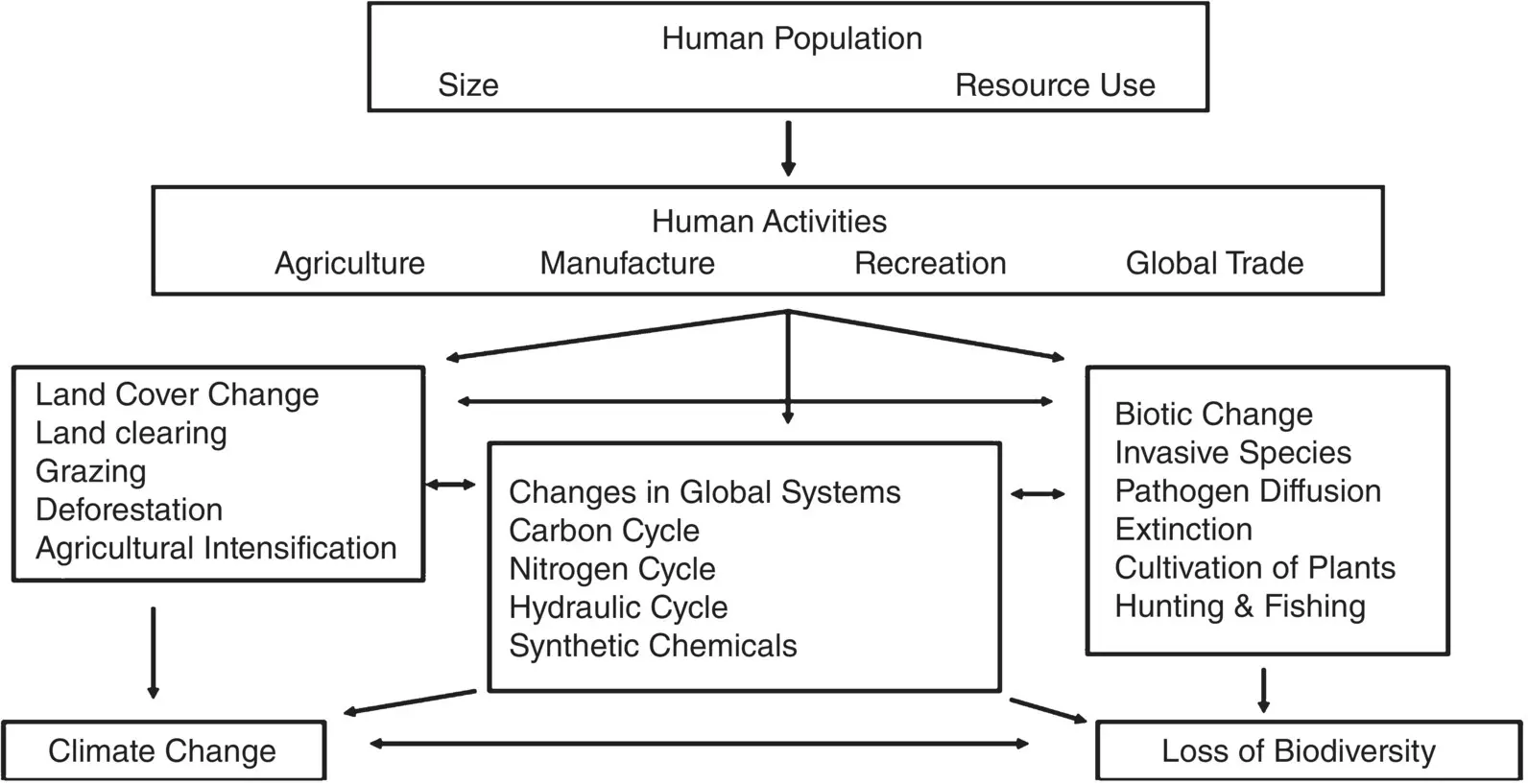

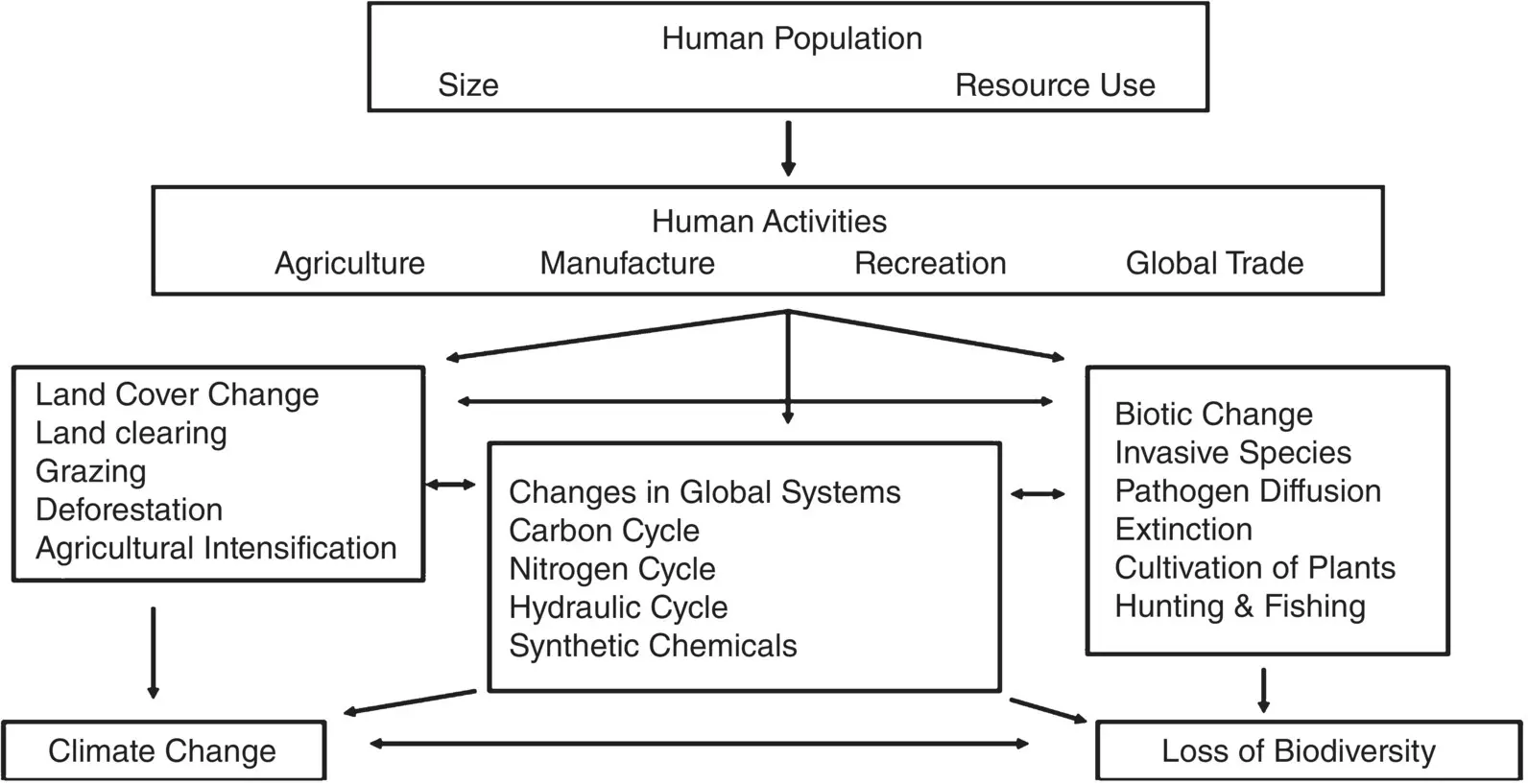

As these examples suggest, and as illustrated in Fig. 1.2, not only are human impacts varied and widespread, but they reveal “how, even on the grandest scale, most aspects of the structure and functioning of Earth’s ecosystems cannot be understood without accounting for the strong, often dominant influence of humanity” (Vitousek et al . 1997, p. 494).

Fig. 1.2 Model of direct and indirect human effects on earth systems.

Source: Modified from Vitousek, P., Mooney, H., Lubchenco, J., & Melillo, J. (1997). Human domination of the Earth's ecosystems. Science 277: 494–499.

1.6 Introducing ecocrises interactions and health

Environmentally speaking, what is a crisis? Further, how do we know we are in a crisis, and when is it time to sound the alarm? What kinds of environmental thresholds must be crossed to recognize we have passed from a noncrisis period into a time of such turbulence and threat that it is aptly called a crisis? Historically, in medicine, dating to the 15th century, “crisis” has referred to a “decisive point in the progress of a disease,” the point at which change must come, for better or worse—toward a return to wellness or toward death (though a new up‐and‐down or slow‐progression “steady state” of chronic illness also occurs). Beyond medicine, the word “crisis” has come to mean an unstable or crucial time or state of affairs in which the possibility of a highly undesirable outcome is possible. With regard to the environment, as Moore (2016) comments, “[t]he conditions of life on planet Earth are changing, rapidly and fundamentally. Awareness of this difficult situation has been building for some time. But the reality of a crisis—understood as a fundamental turning point in the life of a system, any system—is often difficult to understand, interpret, and act upon.”

Part of this difficulty is a result of the complexity of environmental systems and the fact that the environment is constantly changing. Cycles of disruption and recovery are the usual state of environmental affairs (Paine et al . 1998). Another part occurs because we never know everything at once—new and perhaps initially controversial scientific findings are constantly coming to light. Additionally, humans are frequently unready to recognize both the full power of nature and our own capacity to adversely influence it. Finally, there is the intentional denial or even falsification of environmental crises because of the short‐term benefits and profits of maintaining business‐as‐usual practices. As a result, “reasonable treatment of environmental concerns often falls prey to the political agendas of those who have a vested interest in an unsustainable, resource‐extractive approach to economic development” (Hudson 2001).

While cycles of change are the “normal” state in nature, “rapidly compounded perturbations have more serious implications for long‐term alterations of community state, occasionally or even often generating a different assemblage of species” (Paine et al . 1998, p. 536) because the “effect of compounded perturbations is multiplicative, not additive” (Paine et al . 1998, p. 537). In this book, I refer to compounded environmental disturbances as “ecocrises interactions.” Ecocrises interaction—the synergistic interface of two or more environmental events or pollutants that multiply resultant harmful health effects beyond their additive impact—puts both humans and other species at catastrophic risk. This book is designed to increase understanding of the link between health and the environment in times of the ever‐more‐pervasive anthropogenic impacts on natural assemblages. Its specific concern is that the diverse ecological calamities we face are encountered not as standalone threats, which has been the conventional perspective to date, but as adversely interacting events and processes with magnified hazardous effects. The sixth Global Environment Outlook issued by the U.N. Environment Program (2019), a continent‐by‐continent 740‐page assessment written by 250 scientists and experts from more than 70 countries, concludes that because of the perilous combination of climate change, pollution, and the growing human population, the damage already done to the planet is so severe that people’s health will be increasingly threatened unless rapid action is taken. In the view of the report’s authors, without drastically scaled‐up implementation of environmental protections, cities and regions in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa may see millions of premature deaths by mid‐21st century. This discussion raises essential questions about the extinction of populations, species, and ways of life.

Читать дальше