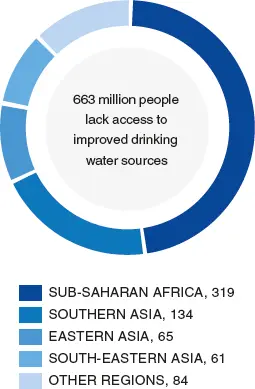

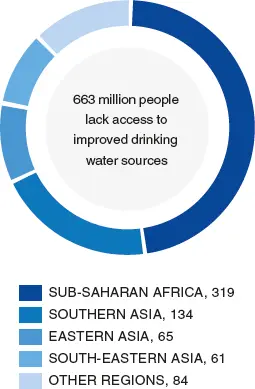

Figure 5.3 Population without access to improved water sources, by region, 2015

Source : UNICEF/WHO (2015: 7).

Progress on sanitation has been slower. The MDG target was for 77 per cent of the global population to be using improved facilities by 2015, but only 68 per cent did so. This represents around 700 million people fewer than the target. Some 2.4 billion people did not have access to improved sanitation; of these, seven out of ten lived in rural areas, as did nine out of ten of those still practising open defecation (UNICEF/WHO 2015: 5). Clearly the MDG targets have proved to be an effective tool for encouraging and measuring progress on the provision of safe water and effective sanitation, but there remains much to be done. As a result, the MDGs were replaced in 2012 with a new set of seventeen interlinked Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), covering poverty reduction, gender equality, climate action, sustainable cities, clean energy, and much more.

Solid waste and recycling

There are very few things we can buy without packaging and, though there are clear benefits, in terms of displaying goods attractively and guaranteeing the safety of products, there are major drawbacks too.

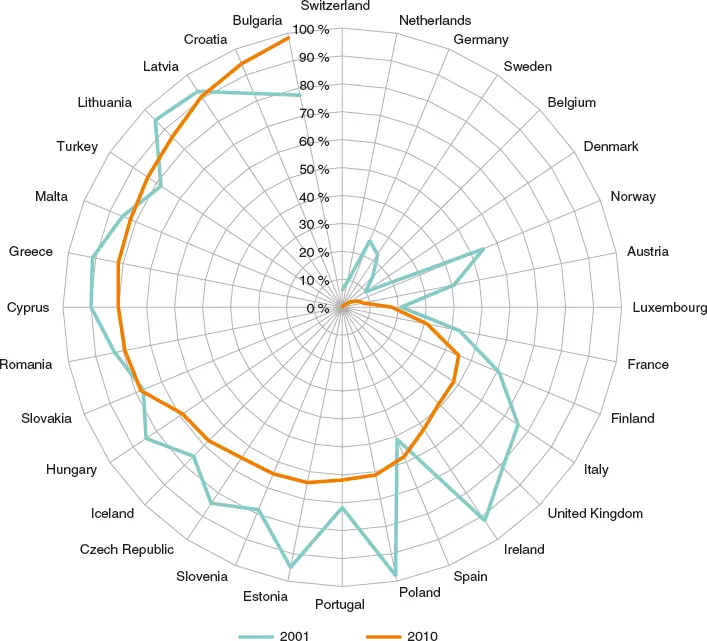

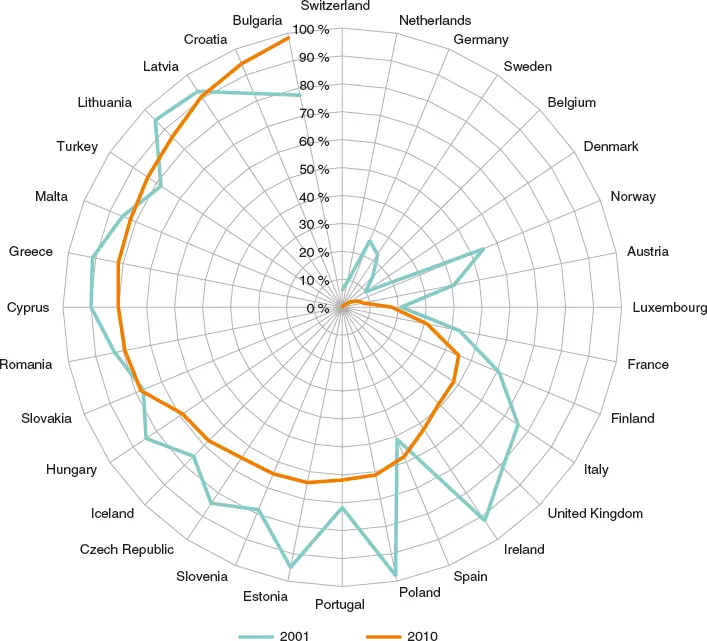

Waste generation is closely tied to the relative prosperity of countries. Poland, Hungary and Slovenia, for example – countries that quite recently moved towards the model of Western capitalism and consumer culture – generate less than half the waste per capita of the USA, Denmark and Australia. However, the more established high-consumption societies do now manage their waste more effectively. As figure 5.4 shows, countries such as Germany, Norway and Ireland are steadily reducing the proportion of waste that ends up in landfill. The European Union aims to become a ‘recycling society’, and there is a move to recycle or compost waste (50 per cent of all municipal waste in the European economic area by 2020) as well as to reduce the amount of packaging used for products at the point of production (European Environment Agency 2013).

The industrialized societies are often called ‘throw-away societies’ because the volume of items discarded as a matter of course is so large. In most countries of the industrialized world, waste collection services are almost universal, but it is increasingly difficult to dispose of the enormous amounts of waste. Landfill sites are becoming full and many urban areas have run out of disposal room. In Scotland, for example, around 90 per cent of household waste was still going to landfill sites in 2006, and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency reported that household waste was growing at 2 per cent per annum.

Figure 5.4 Proportion of municipal waste going to landfill, by European economic area country, 2001 and 2010

Source : European Environment Agency (2013: 21).

The international trade in waste led to the export of plastic waste to China for recycling, where waste was often sorted by hand in poorly regulated working environments that produced environmental degradation. However, in 2018 China banned the import of plastics and other solid wastes for recycling, forcing national governments to look for alternative ways of dealing with their material waste. India and Malaysia followed, banning the importation of solid plastic waste in 2019, and Thailand announced a similar ban from 2021 (Lee 2019).

UK government statistics show that recycling rates increased from 40.4 per cent in 2010 to 45.7 per cent by 2017. Over the same period, the proportion of biodegradable waste going to landfill also fell, from 36 to 21 per cent (Defra 2019b). So, although the amount of household waste has been increasing, more of this is recycled year on year (Defra 2016). Although the amount of household waste recycled may still seem low in comparison with the overall amount produced, a large proportion of what is thrown away cannot be easily reprocessed or reused. Many plastics employed in food packaging simply become unusable waste and have to be buried in refuse tips, where they may remain for centuries. Recycling is becoming a huge industry around the world, but there is still a long way to go to transform the world’s ‘throw-away societies’.

Recycling of household waste has increased as it has become built into the routines of everyday life.

In the developing world, the biggest problem with domestic waste is the lack of refuse collection services. It has been estimated that 20 to 50 per cent of domestic waste in the developing world goes uncollected. Poorly managed waste systems mean that refuse piles up in the streets, contributing to the spread of disease. Over time it is very likely that the developing world will have to deal with problems of waste disposal that are even more acute than those in industrialized countries. This is because, as societies become richer, there is a gradual shift from organic waste, such as food remains, to plastic and synthetic materials, such as packaging, which take much longer to decompose.

Food shortages and biotechnology

In some of the world’s most densely populated areas, people are highly dependent on staple food crops – such as rice – stocks of which are dwindling. Global warming may increase desertification and lead to poor harvests, which has resulted in fears that food shortages may become more widespread. As a result, many worry that present farming techniques will not be able to produce rice yields sufficient to support the growing population. As with many environmental challenges, the threat of famine is not evenly distributed. The industrialized countries have extensive surpluses of grain, but, in the poorer countries, shortfalls are likely to become a chronic problem.

One UK report, based on two years of research into the future of food supplies and farming, argued that the present global food system is not sustainable and cannot end the problem of hunger (Foresight 2011). As the global population grows, from 7 billion to over 8 billion by 2030 and 9 billion by 2050, competition for water, land and energy will intensify and global warming will increase the pressure on food production systems. The combination of these factors constitutes a major threat which demands urgent action. Piecemeal changes will not solve the problem, nor will attempts to achieve national food self-sufficiency. The report argues for a coordinated policy approach and action on four fronts: more food needs to be produced sustainably, demand for resource-intensive foods must be contained, waste in all areas of the food system should be minimized, and political and economic governance of the food system needs to be improved (ibid.: 12–13).

The Foresight report also argues that no policy options or technologies should be closed off in the quest for a sustainable food system, and some scientists and politicians see one key to averting a future food crisis may be advances in biotechnology. By manipulating the genetic composition of basic crops, it is possible to boost a plant’s rate of photosynthesis to produce bigger yields. This process is known as genetic modification, and plants produced this way are called genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Scientists have produced GMOs with higher than normal vitamin content, for example, while other genetically modified crops are resistant to commonly used agricultural herbicides that can be used to kill the weeds around them, as well as insects and fungal and viral pests. Food products that are made from, or contain traces of, GMOs are known as GM foods, and GM crops are sometimes called ‘transgenic’ crops.

Читать дальше