In the early twenty-first century, many car manufacturers invested heavily in less polluting, ‘clean diesel’ cars, claiming that their emission of nitrogen oxide pollutants and CO 2were now low enough to pass the strictest emissions tests. The car-maker Volkswagen made a determined attempt to sell their new diesels into the American market, where they successfully passed the US government’s stringent tests. But in 2015 the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (which had raised concerns in 2014) found that Volkswagen cars had higher emissions ‘on the road’ than in the company’s laboratory tests. Even worse, the EPA found factory-fitted software within the cars – a ‘defeat device’ – which recognized the signs of emissions testing – a stationary vehicle, static steering, air pressure level, and so on – and put the car into an alternative mode which temporarily lowered emissions. Out on the road, the EPA found that the new diesels emitted up to forty times more nitrogen oxide pollutants than US regulations allowed.

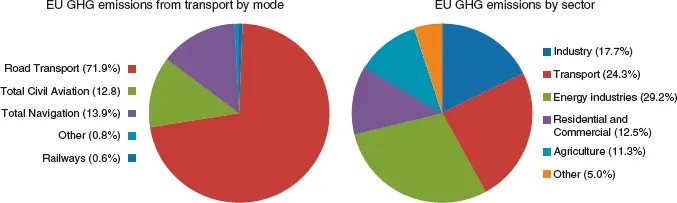

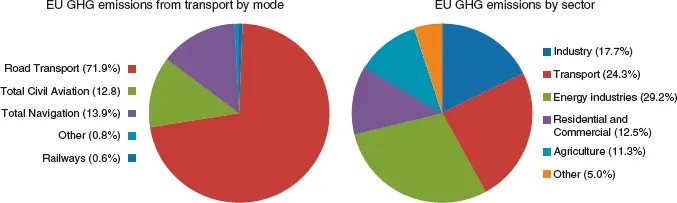

Figure 5.2 EU28 greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by mode of transport and sector, 2012

Source : European Commission (2015a).

Volkswagen admitted trying to cheat the testing regime and acknowledged that around 11 million cars were fitted with the device, 8 million of them in Europe. For the company, emissions testing was merely an obstacle to commercial success, not a means of ensuring better air quality for all. Diesel models from numerous other car-makers, including Nissan, Volvo, Renault, Citroen and Chrysler, were subsequently found to produce more than ten times more nitrous oxide emissions on the road than were claimed by the manufacturers. In 2018, Audi admitted marketing some of its cars with a similar, ‘impermissible software function’ (BBC News 2018e). Large fines were imposed on the companies concerned, and a more realistic testing regime was introduced. The scandal alerts us to the tension that exists between capitalist corporations’ constant pursuit of new markets and profits and environmental regulatory regimes seeking to reduce pollution and protect human health.

See chapter 22, `Crime and Deviance’, for a discussion of corporate criminality.

Persuading people to give up their private cars is proving to be remarkably difficult. List all of the possible reasons why this is the case. What exactly is it that people enjoy about car-ownership, motoring and driving which makes them so reluctant to stop? Do any of these reasons also provide insights into the low take-up of electric cars so far?

Although water is one of the most valuable and essential natural resources, for many years waste products – both human and manufactured – were dumped directly into rivers and oceans with barely a second thought. For instance, in the summer of 1858, the River Thames in London emitted a stench so foul it brought the city to a standstill, forcing politicians to act. Only in the past sixty years or so have concerted efforts been made in many countries to protect the quality of water, to conserve fish stocks and the wildlife that depend on it, and to ensure access to clean water for the global human population.

Water pollution can be understood as contamination of the water supply by toxic chemicals and minerals, pesticides, or untreated sewage, and it poses the greatest threat to people in the developing world. Sanitation systems are underdeveloped in many of the world’s poorest countries, and human waste products are often emptied directly into streams, rivers and lakes. More recently, serious concerns have been raised about the levels of plastic waste that have been discovered in the world’s oceans and coastal regions, much of it being ‘singleuse’ plastics such as drinks bottles, carrier bags and packaging. Regardless of increasing levels of concern, water pollution remains a serious problem in many parts of the world.

Much progress has been made to improve access to safe drinking water. During the 1990s, nearly 1 billion people gained access to safe water and the same number to sanitation, though ensuring safe water supplies remains a problem, particularly in some parts of Africa, where people drink from unprotected wells and springs along with surface water (figure 5.3). The problem may worsen as water supplies in some developing countries are privatized, raising the cost for customers, while the effects of global warming also produce more regular droughts.

One of the ‘Millennium Development Goals’ set by the United Nations in 2000 was to ‘reduce by half the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water’ by 2015. This target was met well ahead of schedule in 2010. By 2015, 91 per cent of the world population had access to improved drinking water sources, and 2.6 billion people had gained such access since 1990. However, in the same year, the Caucasus region, Central Asia, Northern Africa, Oceania and sub-Saharan Africa missed their MDG targets, and some 663 million people – mainly in rural areas – still did not have access to improved sources of safe water (UNICEF/WHO 2015: 4). Many of the least developed countries store around 4 per cent of their annual renewable water flow compared with the 70 to 90 per cent stored in developed countries (UNESCO 2009).

Global society 5.2 Susan Freinkel on our love–hate affair with plastic

Plastic makes up only about 10 percent of all the garbage the world produces, yet unlike most other trash, it is stubbornly persistent. As a result, beach surveys around the world consistently show that 60 to 80 percent of the debris that collects on the shore is plastic. Every year, the Ocean Conservancy sponsors an international beach-cleanup day in which more than a hundred countries now take part…. Whether they’re working a beach in Chile, France, or China, volunteers inevitably come across the same stuff: plastic bottles, cutlery, plates, and cups; straws and stirrers, fast-food wrappers, and packaging. Smoking-related items are among the most common. Indeed, cigarette butts – each made up of thousands of fibers of the semisynthetic polymer cellulose acetate – top every list…. For all the dangers posed by floating bags, castaway lighters, and abandoned nets, the most profound and insidious threat may well be the trillions upon trillions of tiny pieces of plastic speckled across the world’s beaches and scattered through its oceans. These itsy bits, collectively known as microdebris, were scarcely on experts’ radar until recently…. The rise in microdebris is partly due to rising plastics production, which leads to an increase in pellets that can get into the environment: they’re now thought to constitute about 10 percent of all ocean debris. It’s also due to the growing use of teensy plastic beads as scrubbers in household and cosmetic cleaning products and for blasting dirt off ships…. But the main source of microdebris is likely macrodebris: the larger pieces of junked plastic that have been fragmented by the sun and waves. Increasingly, experts fear that these bits are just as dangerous to marine wildlife as the lethal necklaces of packing straps and nylon netting that can choke seals and sharks, and even whales.

Source : Extracts from Freinkel (2011: 127–8 and 134–5).

Pollution of the oceans by a variety of plastic items has only recently come to be seen as a potentially serious environmental problem.

Читать дальше