otium

Latin term for leisure, it includes time spent on reading, writing, and academic activities, including rest. Often associated with the Roman villa as the space for otium .

We must determine the situation of the private rooms for the master of the house, and those which are for general use, and for the guests. Into those which are private no one enters, except invited; such are bed chambers, dining rooms, baths, and others of a similar nature. The common rooms, on the contrary, are those entered by any one, even unasked. Such are the vestibule … the peristyle, and those which are for similar uses.

negotium

Latin term for business (literally “not leisure”), including both public and private business.

atrium

the main or central room of a Roman house, usually directly accessible from the front door.

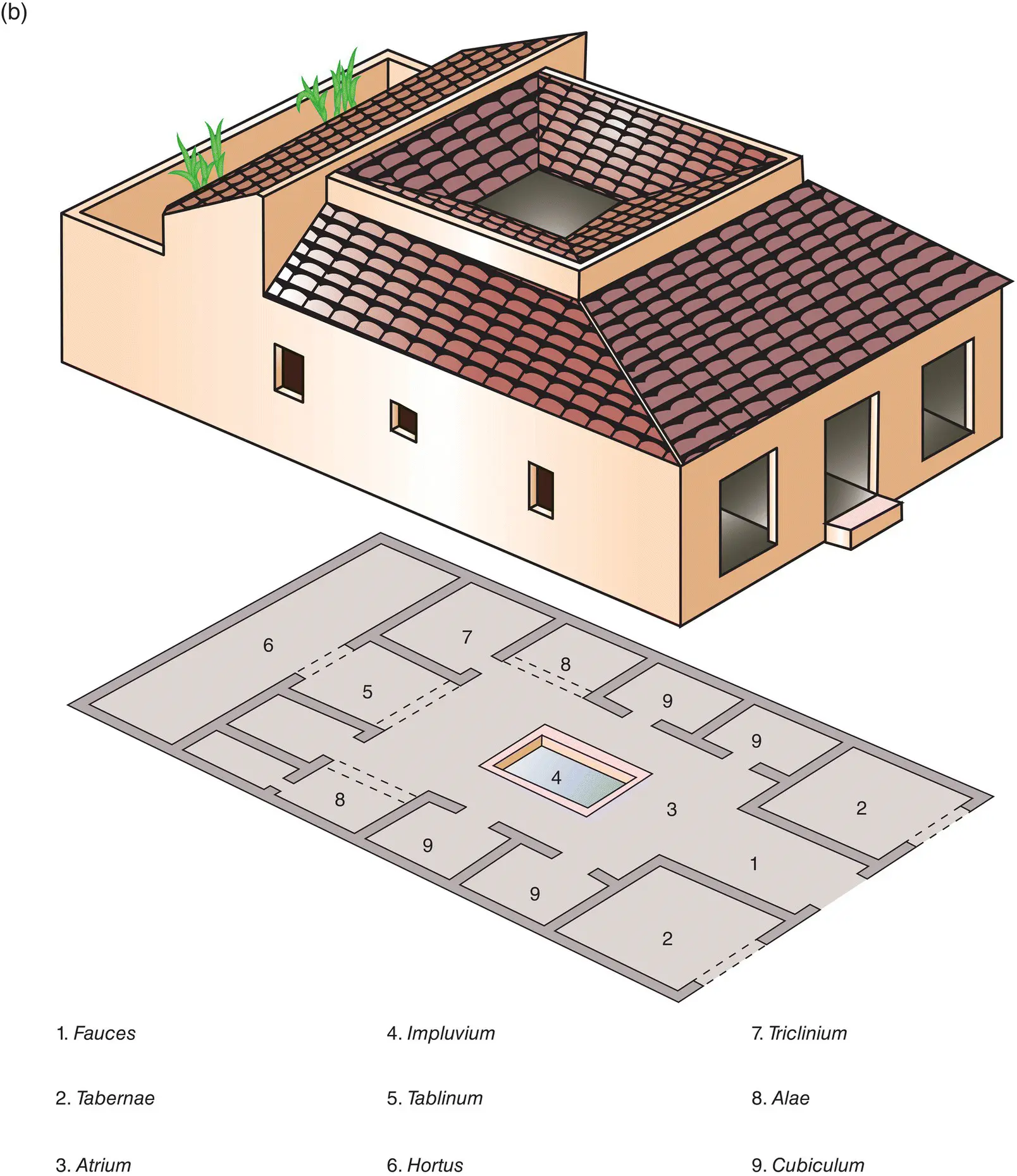

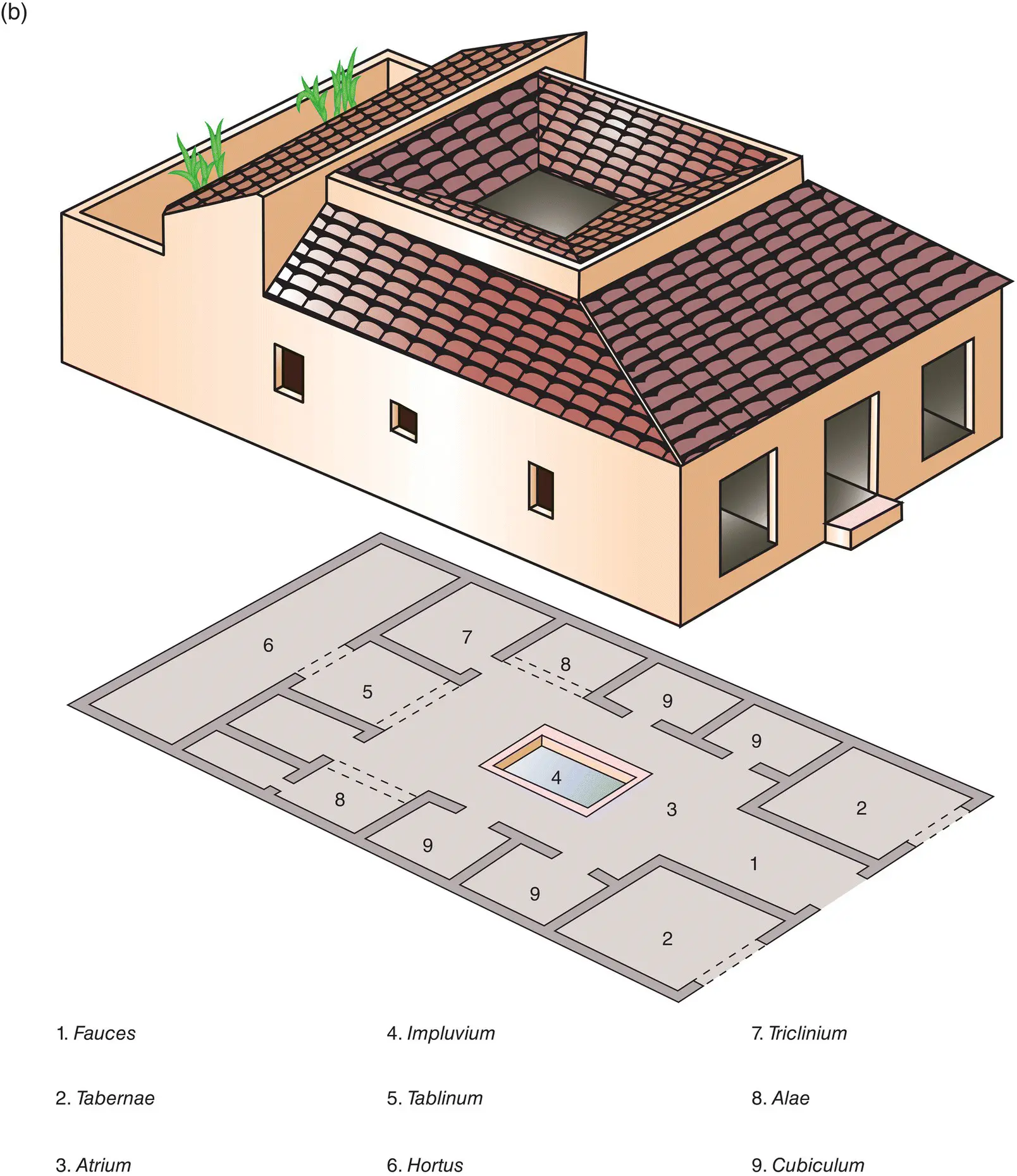

When we examine the layout and rooms of a Roman house, we need to think in Roman terms of public and private, not modern ones. Rather than the default that house = private space, it is critical to think as a Roman would and to distinguish the common rooms from others. The front door of an elite Roman house would have been open throughout the daylight hours and anyone who wished to enter was allowed in. According to Velleius Paterculus (2.14.3) when the architect working for Livius Drusus, Tribune of the Plebs in 91 BCE, promised to make his new house on the slope of the Palatine Hill above the Forum “completely private and free from being overlooked by anyone,” Livius replied, “No, you should apply your skills to arranging my house so that whatever I do should be visible to everybody.” As a result the decor of the front rooms was designed in much the same way a public building was, with a notion of the expected audience. It became a stage to present a public image of the family to those passing on the street and to those who chose to enter. Much of the family’s public image derives from the public service, either civic or military, of the men in the family. The atrium was decorated with their military trophies and achievements, busts of ancestors who had served the state, and this became the means of projecting status. That led to embellishments such as on this house found at Pompeii.

1.13aCutaway of Roman atrium house.

Source: The Visual Dictionary . © QA International, 2020. Reproduced with permission of QA International.

1.13bPlan of Roman atrium house.

Source: Tobias Langhammer. Licensed under CC BY‐SA 3.0.

A wreath called a corona civicadominates the space above the front door. A wreath on the front of a house may say nothing to us, but to the Romans it was special. This is the wreath granted to a Roman citizen for saving the life of another citizen in battle. It was placed above the door to his home and marked out everyone in this domestic space through their association with the honoree of the wreath. The first Roman emperor, Augustus, had a wreath like this marking his front door as well. The benches on either side of the front door are a common feature flanking the doors of wealthy houses at Pompeii. We believe that those with business in the house or visiting it could use them to wait for an audience with the homeowner. Visually, they serve, like the wreath, to mark an elite home, distinguishing it from the houses of people without as much public service.

corona civica

the civic crown, a wreath of oak leaves, a tree sacred to Jupiter, awarded to Roman citizens who saved the lives of other citizens in battle

1.14Facade photo of Roman house, Pompeii.

Photo courtesy Steven L. Tuck.

Finally, it will be useful to introduce here the concept of narrative in art. Much of Roman art tells stories to the viewer and the ways in which those stories were told can differ dramatically. Ability to recognize narrative moments and the types of narrative used by artists can help art historians to analyze works and the meaning intended by the artist. For those stories illustrated by a single episode the moment selected falls into one of four categories: the initial moment of a story, the anticipatory moment (prior to the climax), the climactic moment, or the post‐climactic moment. Each gives a very different image and makes its own demands upon the viewer. The initial moment of the story only implies the further story to come. For example, the relief of a religious ceremony to found a Roman colony (Figure 3.24) need only show a Roman priest plowing while wearing his formal attire to convey the idea of the city about to be founded. The anticipatory moment relies on dramatic tension rather than explicit action to allude to a story. The tomb painting of Achilles and Troilus (Figure 2.23) illustrates the moment just before Achilles attacks and kills Troilus. The climactic moment is often the moment of the greatest action as the battle relief of the monument of Aemilius Paullus (Figure 4.31) uses to great effect. The post‐climactic scene often allows artists to concentrate on the emotional effect of an event or its outcome. The relief of the Emperor Trajan being crowned by Victory herself (Figure 8.23) carries with it the notion of the battles won without showing them more directly.

The various solutions for telling a story with multiple scenes were developed by Greek artists as they worked to create recognizable mythological narration. The major conventions are episodic, continuous, and synoptic narrative. Episodic narrative consists of a story told in a series of separate episodes, usually, but not invariably, arranged in chronological order. The Hadrianic Hunting Tondi (Figure 8.27) with their paired scenes of hunting and post‐hunt sacrifice are episodic. Continuous narrative tells a story in one work of art usually with the same characters portrayed repeatedly to create a sequence. The repeated figures are not separated by borders as are episodic scenes. The Column of Marcus Aurelius (Figure 9.15) exemplifies one of the longest continuous narratives in Roman art. Synoptic narrative occurs when different elements or symbols of a story are placed in one image together to give a synopsis of the overall story. Sometimes devices such as placing the climactic scene in the foreground indicate the narrative sequence. The pediment relief sculpture from Temple A, Pyrgi (Figure 3.5) illustrates synoptic narrative. The figures in the lower foreground represent the climax of the story while those in the background fill out the narrative with pre‐ and post‐climactic secondary events from the same story.

Although these names are not applied explicitly to every work in the following chapters, that’s not to say that they cannot be. You are encouraged to ask which narrative moment a work represents and how that decision affects the presentation and meaning of the art. Your answers to these and other questions on the themes covered can serve as some of the building blocks of art historical studies.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

1 John R. Clarke, Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non‐Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 315 (Berkeley 2003). Examines the art designed for and sometimes created by slaves, former slaves, foreigners, and the free poor in the Roman world.

Читать дальше