Photo courtesy Steven L. Tuck.

To many modern viewers the image of a victorious general – the subject is confirmed by the use of a set of body armor as a strut supporting the left leg – might resemble the “after” photo for an exercise program. It seemingly incongruously combines an idealized, youthful, bulky, muscular body with a craggy, lined face with sagging skin and a wrinkled neck. To a Roman observer it indicates two separate sets of artistic conventions, and therefore cultural values, combined in a single work of art. The craggy portrait face is the Italic tradition conveying the qualities of dignity and maturity of the depicted man, while the muscular youthful body shows the Hellenistic Greek heroization of rulers from the Greek world after the death of Alexander the Great. Together, they merge into a new form of Roman portraiture in the first century BCE. The imagery of victory was important in the Roman world and their readiness to adopt Greek conventions demonstrates the fluidity of the Roman system and its basis on the personal choices of subjects, artists, and patrons.

While modeling the sort of analysis you will find later in the book, mention should be made of the importance of literary reference to our understanding of art. You might think this statue reflects only the personal preference of the person portrayed as a victorious general. In fact, it is only one in a long line of statues that demonstrates broader Roman cultural values as the Roman politician and author Cicero makes clear in his work De Officiis (Concerning Duties 1.61):

When, on the other hand, we wish to pay a compliment, we somehow or other praise in more eloquent strain the brave and noble work of some great soul. Hence there is an open field for orators on the subjects of Marathon, Salamis, Plataea, Thermopylae, and Leuctra [famous battles], and hence our own Cocles, the Decii, Gnaeus and Publius Scipio, Marcus Marcellus, and countless others, and, above all, the Roman People as a nation are celebrated for greatness of spirit. Their passion for military glory, moreover, is shown in the fact that we see their statues usually in soldier’s garb.

1.7Emperor Lucius Verus as victorious athlete, c . 169 CE, Rome. Musei Vaticani, Rome.

Photo courtesy Steven L. Tuck.

Another example of the blending of iconography and projected message is in the statue of a Roman emperor, Lucius Verus, as a victorious athlete. The semantic expression in the statue of Lucius Verus communicates a number of lessons. It is portraiture (giving as the Roman writer, Pliny the Elder, says, “an accurate likeness”), ruler imagery, and a victory monument of a successful military leader (the sword and military cloak near his right foot), but also utilizes the vocabulary of the victorious Greek athlete in its nudity. Roman viewers, depending on their level of visual literacy, could engage the image and any or all of these lessons from it. The fully heroic nudity of Lucius Verus is in contrast to the draped figure from Tivoli. In this case the convention seems to have changed in the more than two hundred years between the two sculptures as nudity is now socially acceptable in an image for a Roman elite male celebrating victory.

Almost a hundred years after the statue of Lucius Verus, the image of another Roman emperor, Trebonianus Gallus, shows another shift in the form and meaning of these victory images. In the case of the Gallus statue, it retains the heroic nudity that first entered Roman art three hundred years earlier from Greek conventions of ruler representation. But here the Greek sculptural proportions, either the Hellenistic ones of the Tivoli general or the Classical ones of Lucius Verus, are abandoned in favor of a completely different set of proportions. The figure has, by Classical conventional terms, a tiny head and undeveloped musculature. But rather than conclude that these features are the result of poor art, as has been argued in the past, it is probably a deliberate attempt to exploit the traditional imagery of the victorious ruler/athlete with an image that conveys the massive power of the emperor over his pretensions of Classical cultural connections. The issue of judging art and its values and class connections is an important topic and one that art historians debate, as did the Romans.

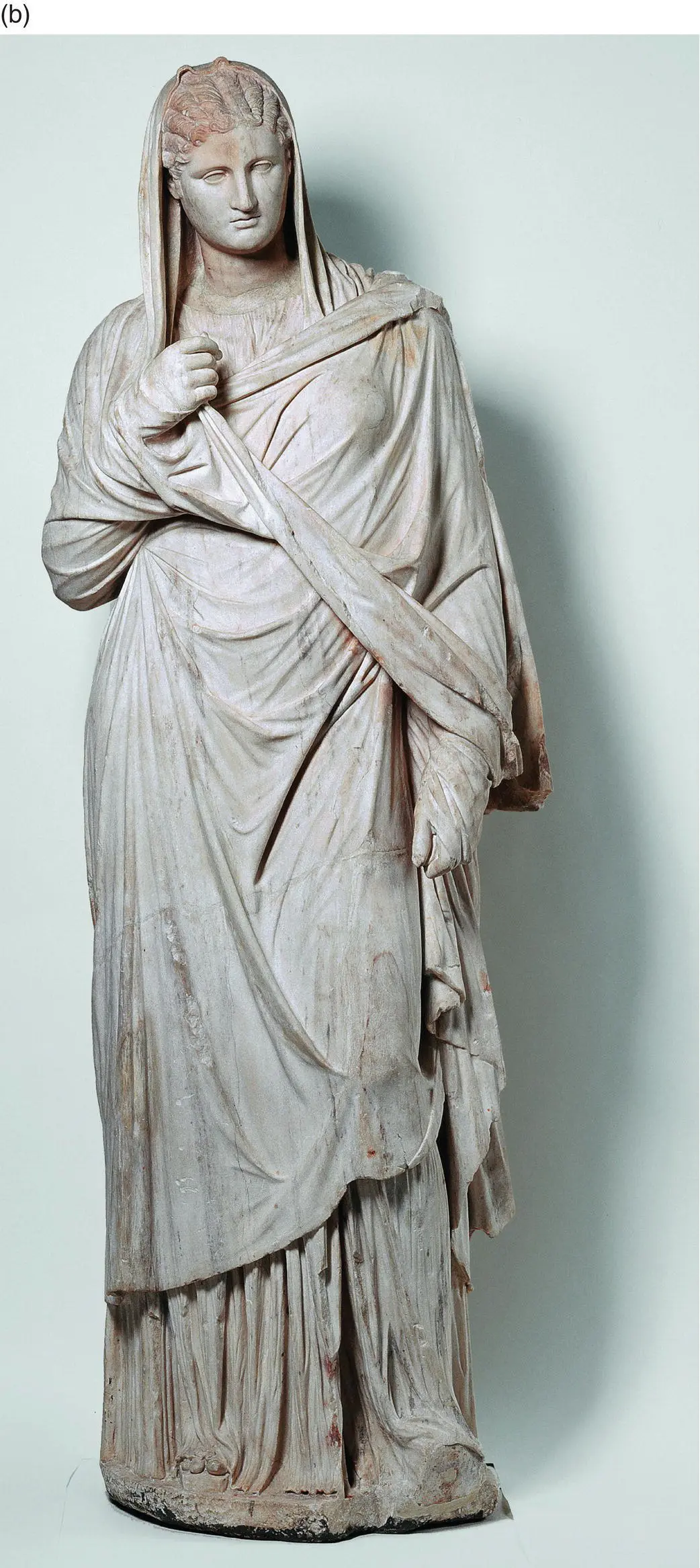

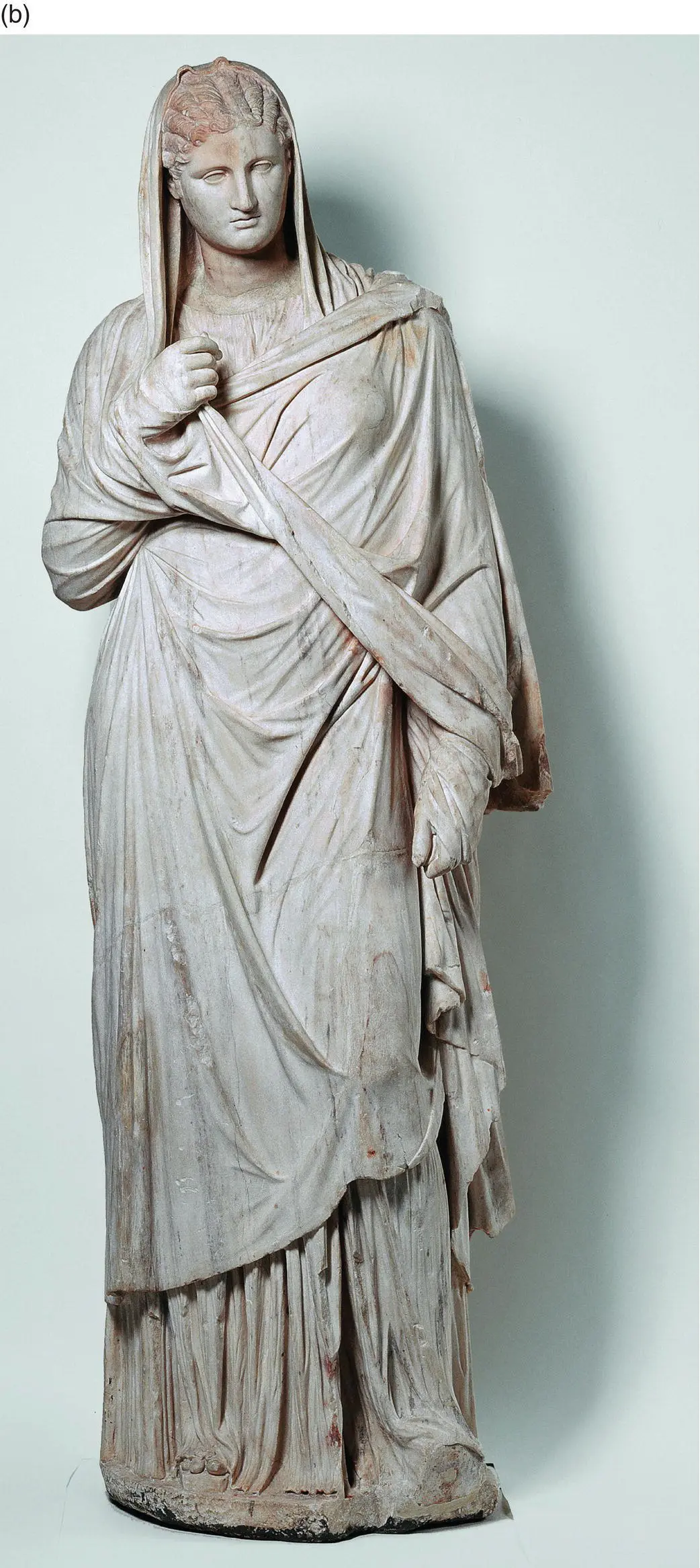

FEMALE PORTRAITURE AND EMBEDDED VALUES

In 1711 in southern Italy workmen digging a well hit a set of ancient statues that were part of the remains of the city of Herculaneum, destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. Two of these have become known as the Large and Small Herculaneum Woman statues. Both of the standing women are dressed in a combination of a dress and mantle, the traditional dress for elite Roman women. The Large Herculaneum Woman has her mantle pulled up to cover her head, a sign of piety. The Small Herculaneum Woman seems to be younger, possibly unmarried, and pulls her mantle around her body in a gesture of modesty.

If these were unique statues, they might not be worth discussing here, but they are not. Far from it. In fact, more than 180 copies or variations of the Large Woman type and 160 of the Small Woman type are now known along with a number of variations in relief on tombstones and sarcophagi. The majority have individualized facial features, some amounting to portraits, indicating that the types were widespread throughout the Roman world. Their popularity derived at least in part from their ability to convey elite female values through the figures’ poses and dress.

1.8Trebonianus Gallus bronze portrait, 251–253 CE, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. H 95 in (241.3 cm).

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

1.9a and 1.9bSmall Herculaneum Woman Statue, 1st cent. CE, Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, H 71 ¼ in (1.8 m), and Large Herculaneum Woman Statue, 1st cent. CE, Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, H 78 in (1.98 m).

Source: (a) © Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photos: Ingrid Geske. (b) Bridgeman Images.

ROMANS JUDGING ROMAN ART: VALUES AND CLASS

On the issue of judging art, its projected values, and the class connections it conveys, we need to avoid bringing our own class values and judgments with us as we examine the art. However, we need to be aware of and take into account ancient Roman class conventions and judgments. For this, the study of the art can be greatly helped by ancient literary sources in which authors comment on the art, its meaning, and contemporary attitudes towards it. Nowhere is that made more explicit than for still life paintings. A property in Pompeii, labeled on the outside in a for rent sign as the Praedia (estate) of Julia Felix, was decorated on the interior with a series of wall paintings. A number of these featured panels of still life scenes in which the images concentrated on food products. But these were food products of two particular types. One of these is obsoniaand the other is xenia.

Читать дальше