The stereotype includes the idea that hunting–gathering people were always on the verge of starvation and that the pursuit of food took so much of their time and energy that there was not enough of either one left over to build more “advanced” cultures. Hunters were too nomadic to cultivate plants and too ignorant or unintelligent to understand the life cycles of plants. The idea of sowing or planting had never occurred to them and they lacked the intelligence to conceive of it. Hunters were concerned with animals and had no interest in plants. In the stereotype that developed, it was generally agreed that the life of the hunter‐gatherer was “nasty, brutish, and short,” and that any study of such people would only reveal that they lived like animals, were of low intelligence, and were intellectually insensitive and incapable of “improvement.”

Occasionally, an unusually perceptive student of mankind tried to point out that hunting man might be as intelligent as anyone else; that he had a sensitive spiritual and religious outlook; that he was capable of high art; that his mythologies were worthy of serious consideration; and that he was, in fact, as one of us and belonged to the same species with all its weaknesses and potentialities. Such opinions were seldom taken very seriously until recent years. It has finally become apparent that no part of the stereotype is correct and that widely held presuppositions are all completely false and untenable. Our ancestors were not as stupid or as brutish as we wanted to believe.

In 1966, Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore organized a symposium on Man the Hunter held at the University of Chicago and published in 1968. Lee reported on his studies of the San !Kung of the Dobe area, Botswana. Over a three‐week period, Lee (1968) found that !Kung Bushmen spent 2.3, 1.9, and 3.2 days for the first, second, and third week, respectively, in subsistence activities. He wrote, “In all, the adults of the Dobe camp worked about 2 ½ days a week. Since the average working day was about 6 hr long, the fact emerges that !Kung Bushmen of Dobe, despite their harsh environment, devote from 12 to 19 hr a week to getting food.”

Among the Bushmen, neither the children nor the aged are pressed into service. Children can help if they wish, but are not expected to contribute regularly to the work force until they are married. The aged are respected for their knowledge, experience, and legendary lore; and are cared for even when blind or lame or unable to contribute to the food‐gathering activities. Neither nonproductive children nor the aged are considered a burden.

To the !Kung Bushman, the mongongo nut [ Schinziophyton rautanenii (Schinz) Radcl.‐Sm] is basically the staff of life. These nuts are available year‐round and are remarkably nutritious ( Table 1.1). The average daily per‐capita consumption of 300 nuts weighs “only about 7.5 ounces (212.6 g) but contains the caloric equivalent of 2.5 pounds (1134 g) of cooked rice and the protein equivalent of 14 ounces (397 g) of lean beef” (Lee, 1968). Lee found the diet adequate, starvation unknown, the general health good, and longevity about as good as in modern industrial societies. The average of 2140 calories per person daily ( Table 1.1) compares favorably to the 2015 USDA recommendations of 2400–3000 calories for an adult male and 1800–2400 calories for an adult female ( https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/appendix‐2/).

Table 1.1 Diet of the !Kung Bushmen.

Source: Adapted from Lee (1968).

|

Protein (g/day) |

Calories per person per day |

Percent caloric contribution of meat and vegetables |

| Meat |

34.5 |

690 |

33 |

| Mongongo nuts |

56.7 |

1,260 |

67 |

| Other vegetable foods |

1.9 |

190 |

|

| Total |

93.1 |

2,140 |

100 |

Sahlins (1968) came in with almost identical figures for subsistence activities of the Australian Aborigines he studied and elaborated on his term “original affluent society.” One can be affluent, he said, either by having a great deal or by not wanting much. If one is consistently on the move and must carry all one's possessions, one does not want much. The Aborigines also appeared to be well fed and healthy, and enjoyed a great deal of leisure time.

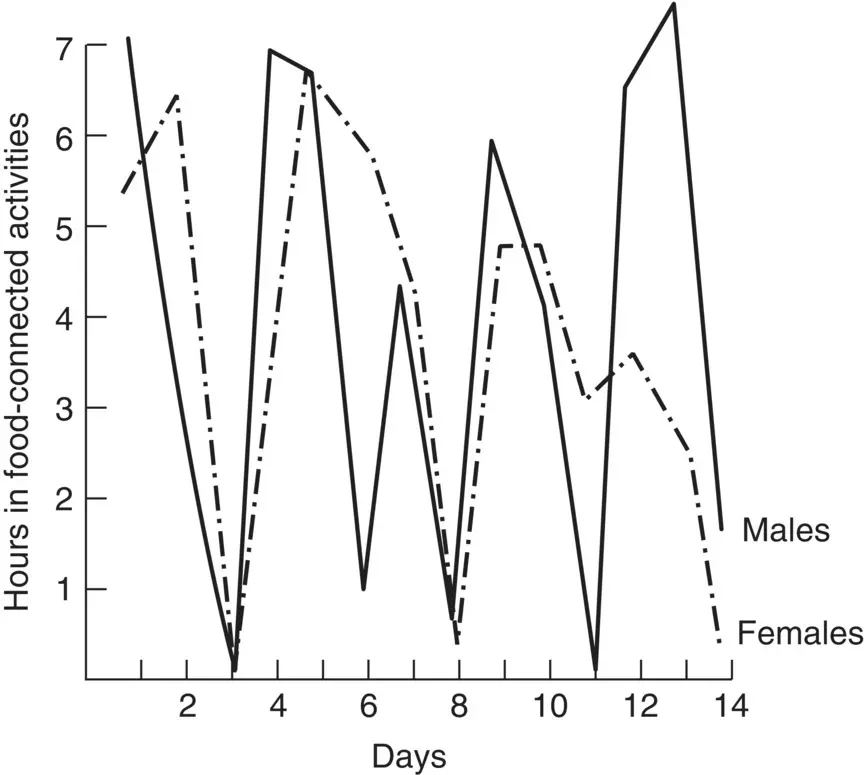

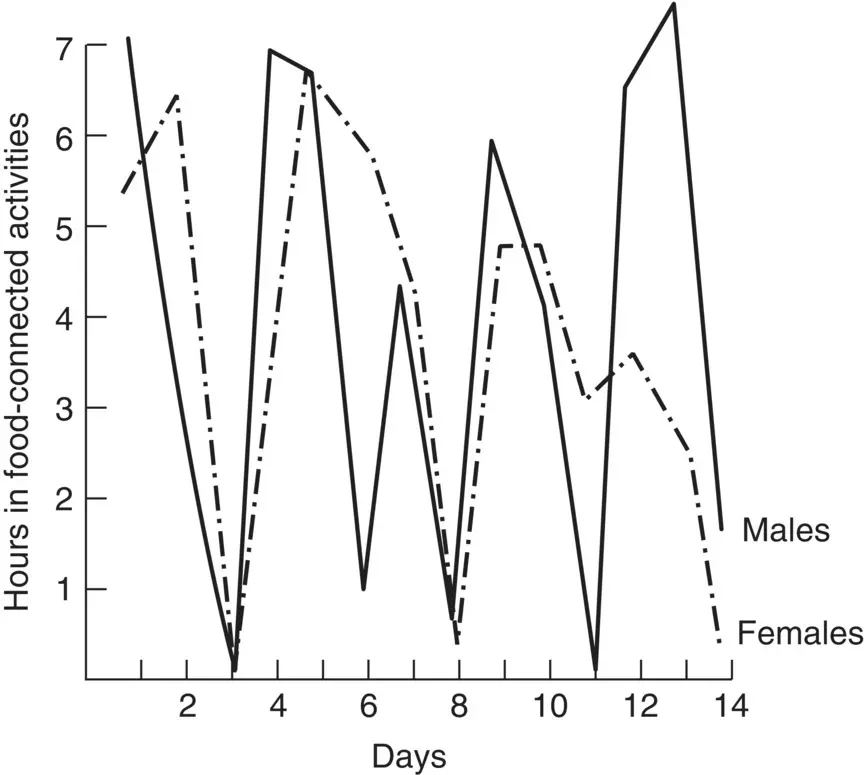

Gatherers can obtain food in abundance even in the deserts of Australia and the Kalahari Desert of Africa. The rhythm of food‐getting activities is almost identical between the Australian Aborigine and the !Kung Bushmen of southern Africa. The women and children are primarily involved in obtaining plant and small animal materials. Hunting is reserved for males at the age of puberty or older but is more of a sport than a necessity. Meat is a welcome addition to a rather dull diet but is seldom required in any abundance for adequate nutrition. Both males and females tend to work for 2 days and every third day is a holiday ( Figure 1.1). Even during the days they work, only about 3–4 hr per day are employed to supply food for the entire group (Australian data presented by Sahlins, 1968).

Figure 1.1 Food‐gathering activities of the Australian Aborigines.

Source: Adapted from Sahlins (1968).

Other reports at the symposium tended to support these general findings. A picture emerged of leisure, if not affluent societies, where the food supply was assured even under difficult environmental conditions and could be obtained from natural sources with little effort. The picture described did seem to fit the golden age of Hesiod or the Biblical Garden of Eden.

The publication of Man the Hunter was a surprise to many who believed some version of the hunter stereotype. The stimulation was enormous. Between 1968 and 1992, there were at least 12 international conferences on hunter‐gatherers as a direct result, but not all were published. A few of the early conferences included ones published by Ingold et al. (1988a, 1988b) and by Schire (1984). In addition, one may cite Bicchieri (1972), Hunters and Gatherers Today ; Dahlberg (1981), Woman, the Gatherer ; Winterhalder and Smith (1981), Hunter‐gatherer Foraging Strategies ; Williams and Hunn (1982), Resource Managers : North American and Australian Hunter‐gatherers ; Koyama and Thomas (1982), Affluent Foragers: Pacific Coasts East and West ; Price and Brown (1985), Prehistoric Hunter‐gatherers: The Emergence of Social and Cultural Complexity ; Harris and Hillman (1989), Foraging and Farming: The Evolution of Plant Exploitation ; and such regional treatments as Hallam (1975), Fire and Hearth: A Study of Aboriginal Usage and European Usurpation in Southwestern Australia ; Silberbauer (1981, p. 242), Hunter and Habitat in the Central Kalahari Desert ; Riches (1982), Northern Nomadic Hunter‐gatherers ; Lee (1984), The Dobe!Kung ; Akazawa and Aikens (1986), Prehistoric Hunter‐gatherers in Japan ; and there are many hundreds of additional research papers. There is now a vast amount of new material on the subject, but some of the oldest papers are still the most useful because observations were made before the hunter‐gatherers were so restricted and encapsulated as they are now.

The biases of some of the investigators were often clear. Some set out to dispute the “affluent society” concept and others to support it. Some of the anthropologists were hung up on Marxist views of “history,” since the egalitarian nature of most hunter‐gatherer societies suggested Marx's view of communism: “No one starves unless all starve”; “no man need go hungry while another eats”; “rich and poor perish together,” and so forth (Lee, 1988). The quotes are from observers of Iroquois, Ainu, and Nuer, respectively, and seem to equate egalitarianism with hunger, which is probably not fair. Incidentally, Karl Marx took his model of basic communism from an agricultural Iroquois society, not from hunter‐gatherers, who are not so likely to starve.

Читать дальше