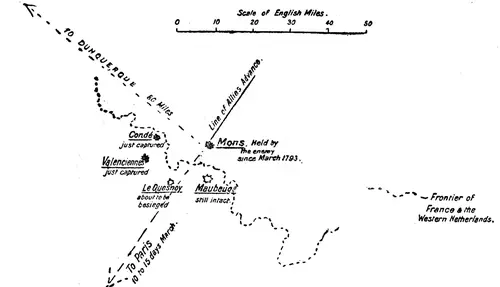

There is the picture of that sudden internal struggle which coincides with this moment of the revolutionary war, the moment of the fall of Condé and of Valenciennes, and the exposure of the frontier.

The second point, the advent of Carnot into the Committee of Public Safety, which has already been touched upon in the political part of this work, has so preponderating a military significance that we must consider it here also.

The old Committee of Public Safety, it will be remembered, reached the end of its legal term on July 10. It was the Committee which the wisdom of Danton had controlled. The members elected to the new Committee did not include Carnot, but the military genius of this man was already public. He came of that strong middle class which is the pivot upon which the history of modern Europe turns; a Burgundian with lineage, intensely republican, he had been returned to the Convention and had voted for the death of the King; a sapper before the Revolution, and one thoroughly well grounded in his arm and in general reading of military things, he had been sent by the Convention to the Army of the North on commission, he had seen its weakness and had watched its experiments. Upon his return he was not immediately selected for the post in which he was to transform the revolutionary war. It was not until the 14th of August that he was given a temporary place upon the Committee which his talents very soon made permanent. He was given the place merely as a stopgap to the odious and incompetent fanatic, Saint-André, who was for the moment away on mission. But from the day of his admission his superiority in military affairs was so incontestable that he was virtually a dictator therein, and his first action after the general lines of organisation had been laid down by him was to impose upon the frontier armies the necessity of concentration. He introduced what afterwards Napoleon inherited from him, the tactical venture of "all upon one throw."

It must be remembered that Carnot's success did not lie in any revolutionary discovery in connection with the art of war, but rather in that vast capacity for varied detail which marks the organiser, and in an intimate sympathy with the national character. He understood the contempt for parade, the severity or brutality of discipline, the consciousness of immense powers of endurance which are in the Frenchman when he becomes a soldier;—and he made use of this understanding of his.

It must be further remembered that this powerful genius had behind him in these first days of his activity the equally powerful genius of Danton; for it was Danton and he who gave practical shape to that law of conscription by which the French Revolution suddenly increased its armed forces by nearly half a million of men, restored the Roman tradition, and laid the foundation of the armed system on which Europe to-day depends. With Carnot virtually commander-in-chief of all the armies, and enabled to impose his decisions in particular upon that Army of the North which he had studied so recently as a commissioner, the second factor of the situation I am describing is comprehended.

The third, as I have said, was the English diversion upon Dunquerque.

The subsequent failure of the Allies has led to bitter criticism of this movement. Had the Allies not failed, history would have treated it as its contemporaries treated it. The forces of the Allies on the north-eastern frontier were so great and their confidence so secure—especially after the fall of Valenciennes—that the English proposal to withdraw their forces for the moment from Coburg's and to secure Dunquerque, was not received with any destructive criticism. Eighteen battalions and fourteen squadrons of the Imperial forces were actually lent to the Duke of York for this expedition. What is more, even after that diversion failed, the plan was fixed to begin again when the last of the other fortresses should have fallen: so little was the English plan for the capture of the seaport disfavoured by the commander-in-chief of the Allies.

That diversion on Dunquerque turned out, however, to be an error of capital importance. The attempt to capture the city utterly failed, and the victory which accompanied its repulsion had upon the French that indefinable but powerful moral effect which largely contributed to their future successes.

The accompanying sketch map will explain the position. Valenciennes and Condé have fallen; Lequesnoy, the small fortress subsidiary to Valenciennes, has not yet been attacked but comes next in the series, when the moment was judged propitious for the detachment of the Anglo-Hanoverian force with a certain number of Imperial Allies to march to the sea.

It must always be remembered by the reader of history that military situations, like the situations upon a chess board, rather happen than are designed; and the situation which developed at the end of September upon the[Pg 187]

[Pg 188] extreme north and west of the line which the French were attempting to hold against the Allies was strategically of this nature. When the Duke of York insisted upon a division of the forces of the Allies and an attack upon Dunquerque, no living contemporary foresaw disaster.

Showing condition of the frontier fortresses blocking the road to Paris when the expedition to Dunquerque was decided upon. August 1793.

Coburg, indeed, would have preferred the English to remain with him, and asked them to do so, but he felt in no sort of danger through their temporary absence, nor, as a matter of fact, was he in any danger through it.

Again, though the positions which the Duke of York took up when he arrived in front of Dunquerque were bad, neither his critics at home, nor any of his own subordinates, nor any of the enemy, perceived fully how bad they were. It was, as will presently be seen, a sort of drift, bad luck combined with bad management, which led to this British disaster, and (what was all-important for the conduct of the war) to the first success in a general action which the French had to flatter and encourage themselves with during all that fatal summer.

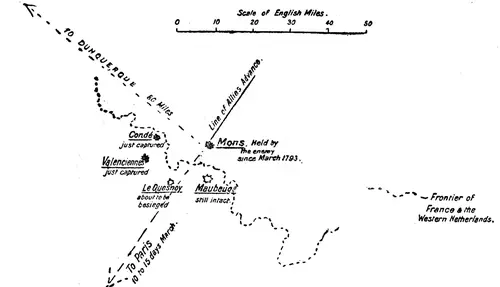

The Duke of York separated his force from that of Coburg just before the middle of August; besides the British, who were not quite 7,000 strong, 11,000 Austrians, over 10,000 Hanoverians and 7,000 Hessians were under his command. The total force, therefore, was nearly 37,000 strong. No one could imagine that, opposed by such troops as the French were able to put into line, and marching against such wretched defences as those of Dunquerque then were, the Duke's army had not a perfectly easy task before it; and the plan, which was to take Dunquerque and upon the return to join the Austrian march on Paris, was reasonable and feasible.

It is important that the reader should firmly seize this and not read history backward from future events.

Certain faults are to be observed in the first conduct of the march. It began on the 15th of August, proceeding from Marchiennes to Menin, and at the outset displayed that deplorable lack of marching power which the Duke of York's command had shown throughout the campaign. 6From Marchiennes to Tourcoing is a long day's march: it took the Duke of York four days; and, take the march altogether, nine days were spent in covering less than forty miles. In the course of that march, the British troops had an opportunity of learning to despise their adversary: they found at Linselles, upon the flank of their advance, a number of undisciplined boys who broke the moment the Guards were upon them, and whose physical condition excited the ridicule of their assailants. The army proceeded after this purposeless and unfruitful skirmish to the neighbourhood of the sea coast, and the siege of Dunquerque was undertaken under conditions which will be clear to the reader from the following sketch map.

Читать дальше