I remembered as I sat there how a boy, a half-wit, had told me on a pass in Cumberland that a great battle had been fought there between two kings; he did not know how long ago, but it had been a famous fight. I did not believe him then, but I know now that he had hold of a tradition, and the king who fought there was not a George or a James, but Rufus, eight hundred years before. As I considered these things and other memories halting at this place, I came to wish that all history should be based upon legend. For the history of learned men is like a number of separate points set down very rare upon a great empty space, but the historic memories of the people are like a picture. They are one body whose distortion one can correct, but the mass of which is usually sound in stuff, and always in spirit.

Thinking these things I went down the hill with my companions, and I reoccupied my mind with the influence of that great and particular story of St. Thomas, whose shadow had lain over the whole of this road, until in these last few miles it had come to absorb it altogether.

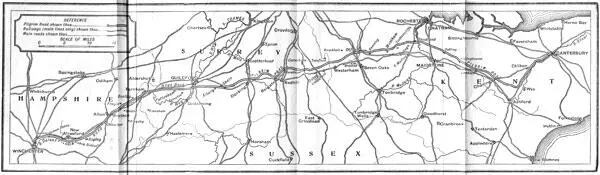

The way was clear and straight like the flight of a bolt; it spanned a steep valley, passed a windmill on the height beyond, fell into the Watling Street (which here took on its alignment), and within a mile turned sharp to the south, crossed the bridge, and through the Westgate led us into Canterbury.

We had thoroughly worked out the whole of this difficult way. There stood in the Watling Street, that road of a dreadful antiquity, in front of a villa, an omnibus. Upon this we climbed, and feeling that a great work was accomplished, we sang a song. So singing, we rolled under the Westgate, and thus the journey ended.

* * * * *

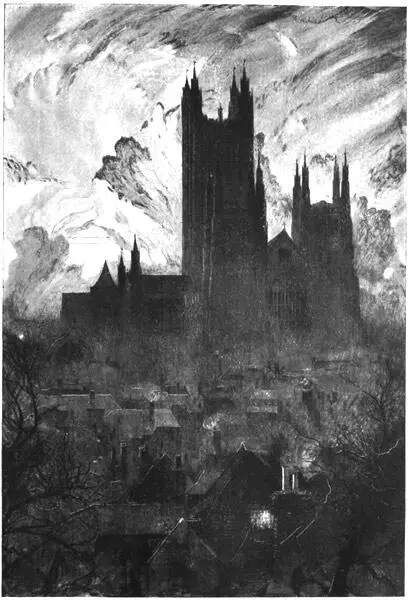

There was another thing to be duly done before I could think my task was over. The city whose name and spell had drawn to itself all the road, and the shrine which was its core remained to be worshipped. The cathedral and the mastery of its central tower stood like a demand; but I was afraid, and the fear was just. I thought I should be like the men who lifted the last veil in the ritual of the hidden goddess, and having lifted it found there was nothing beyond, and that all the scheme was a cheat; or like what those must feel at the approach of death who say there is nothing in death but an end and no transition. I knew what had fallen upon the original soul of the place. I feared to find, and I found, nothing but stones.

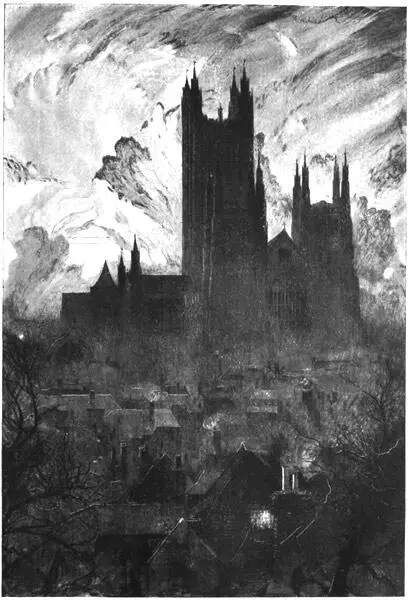

I stood considering the city and the vast building and especially the immensity of the tower.

Even from a long way off it had made a pivot for all we saw; here closer by it appalled the senses. Save perhaps once at Beauvais, I had never known such a magic of great height and darkness.

SUCH A MAGIC OF GREAT HEIGHT AND DARKNESS

It was as though a shaft of influence had risen enormous above the shrine: the last of all the emanations which the sacred city cast outwards just as its sanctity died. That tower was yet new when the commissioners came riding in, guarded by terror all around them, to destroy, perhaps to burn, the poor materials of worship in the great choir below: it was the last thing in England which the true Gothic spirit made. It signifies the history of the three centuries during which Canterbury drew towards it all Europe. But it stands quite silent and emptied of every meaning, tragic and blind against the changing life of the sky and those activities of light that never fail or die as do all things intimate and our own, even religions. I received its silence for an hour, but without comfort and without response. It seemed only an awful and fitting terminal to that long way I had come. It sounded the note of all my road—the droning voice of extreme, incalculable age.

As I had so fixed the date of this journey, the hour and the day were the day and hour of the murder. The weather was the weather of the same day seven hundred and twenty-nine years before: a clear cold air, a clean sky, and a little wind. I went into the church and stood at the edge of the north transept, where the archbishop fell, and where a few Norman stones lend a material basis for the resurrection of the past. It was almost dark. … I had hoped in such an exact coincidence to see the gigantic figure, huge in its winter swaddling, watching the door from the cloister, watching it unbarred at his command. I had thought to discover the hard large face in profile, still caught by the last light from the round southern windows and gazing fixedly; the choir beyond at their alternate nasal chaunt; the clamour; the battering of oak; the jangle of arms, and of scabbards trailing, as the troops broke in; the footfalls of the monks that fled, the sharp insults, the blows and Gilbert groaning, wounded, and à Becket dead. I listened for Mauclerc's mad boast of violence, scattering the brains on the pavement and swearing that the dead could never rise; then for the rush and flight from the profanation of a temple, and for distant voices crying outside in the streets of the city, under the sunset, 'The King's Men! The King's!'

But there was no such vision. It seems that to an emptiness so utter not even ghosts can return.

* * * * *

In the inn, in the main room of it, I found my companions. A gramophone fitted with a monstrous trumpet roared out American songs, and to this sound the servants of the inn were holding a ball. Chief among them a woman of a dark and vigorous kind danced with an amazing vivacity, to the applause of her peers. With all this happiness we mingled.

1.The sacredness of wells is commingled all through Christendom with that of altars. As, for instance, the wells in the cathedrals of Chartres, of Nimes, of Sangres, and in St. Nicholas of Bari. In Notre Dame at Poissy, in St. Eutropius at Santes (a Roman well), in the Augustinian chapel at Avignon (now a barracks). In Notre Dame at Etampes there are three wells. There is a well in St. Martin of Tours, in the Abbey of Jobbes, in the Church of Gamache. Our Lady of the Smithies at Orleans (now pulled down) had a well into which Ebroin threw St. Leger, the Bishop; and close by at Patay there is one in St. Sigismund's into which Chlodomir threw some one or other. Old Vendée is full of such sacred wells. The parish church of Praebecq has one, of Perique, of Challans (filled up in fourteenth century). At Cheffoi you can see one in full use, right before the high altar and adorned with a sculpture of the woman at the well—and this is but a short and random list.

2.See upon this abandoned portion Mr. Shore's article in the third volume of the Archæological Review .

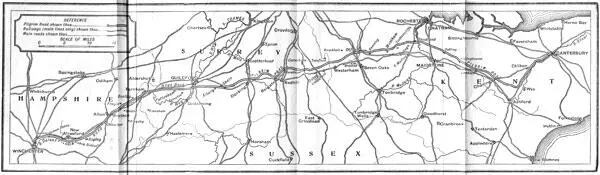

3.The points where the pilgrims obviously left the Old Road are Compton (p. 160) and Burford Bridge (p. 181). They probably left it after Merstham (p. 205) and perhaps after Chilham (p. 271), while they certainly confused the record of the passages of the Wey (p. 165), and perhaps of the Medway (p. 242). As for their supposed excursion into the plain near Oxted (p. 213), I can find no proof of it. The places where other tracks coming in impair the Old Road are on either side of the Mole (p. 181), the Darent (p. 222), and the Medway (p. 237), where, along such river valleys, such tributaries would naturally lead.

4.See note on p. 158.

5.In the case of three—those of Gatton, Arthur's Seat, and Godmersham—an excellent reason can at once be discovered. The Road goes just north of the crest, in order to avoid the long circuit of a jutting-out spur with its re-entrant curve. For that re-entrant curve, it must be remembered, would be worse going, and wetter, than even the short excursion to the north of the crest. In the fourth case, however, where the Road goes to the north for a few hundred yards behind Weston Wood, I can offer no explanation of the cause. It is sufficiently remarkable that in all this great distance there should be but that one true exception to the rule, and a characteristic so universal permits me, I think, to take it for certain in one doubtful place (Chilham) that the Road has followed the sunny side of the slope.

Читать дальше