Where product markets are experiencing an episode of deregulation or other turbulence. Deregulation of markets invites entry by firms in related industries. The merger of Citicorp and Travelers insurance (see Carow 2002) reflected the deregulation of commercial banking in the United States permitting “bancassurance,” the convergence of commercial banking and insurance industries. Also, during periods of product market uncertainty, a disciplined and patient investor may be better at allocating capital into that industry than would a more volatile public capital market.

Where one or both firms have significant information-based assets. There is evidence that diversified firms transfer knowledge and intellectual capital more efficiently than do public markets. Thus, Morck and Yeung (1997) find that diversification pays when the parent and target are in information-intensive industries.

VALUE CREATION DISCIPLINE IS VITAL; AVOID MOMENTUM LOGICGrowth can become a narcotic, such that growing well matters less than growing by any means. Chapter 17describes the economics of momentum strategies in detail. If strong discipline is maintained, it is possible to grow in a way that creates value for shareholders. Indeed, one of the best-performing stocks of the past 40 years has been Berkshire Hathaway, nominally an insurance company but actually a quirky conglomerate run by Warren Buffett, with interests in furniture retailing, razor blades, airlines, paper, broadcasting, soft drinks, and publishing. Buffett’s success seems to say that instead of debating diversification and focus, one should simply concentrate on sound investing and value-oriented management. Study Warren Buffett not as a stock investor but as a CEO of a conglomerate. While we know a lot about his philosophy of value-oriented investing, we know much less about how he finds and manages his diversifying acquisitions.

PERHAPS DIVERSIFICATION AND FOCUS ARE PROXIES FOR SOMETHING ELSEIf the choice of strategy (diversification or focus) does not help us discriminate well across outcomes, then perhaps we should look elsewhere for explanations of where strategy has an impact. One could look more deeply to the drivers of the returns in these transactions, such as governance systems, financial discipline, transparency of results, managerial talent, incentive compensation, and so on. Research on these is discussed elsewhere in this book and finds that the drivers are significant in explaining outcomes.

PRESUPPOSE RATIONALITY, BUT GUARD AGAINST STUPIDITYPay attention as future research unfolds. Growth by diversification is one of the strategic staples for corporations, easily abused and misused. If, as Nobel laureate George Stigler once argued, rational people don’t do stupid things repeatedly, firms must be diversifying because there is something in it. One wants to understand the economic consequences of diversification. The evolution from one view to another evokes similar shifts in other areas of M&A, such as poison pills and the perennial question of whether M&A destroys value for bidders.

The design of good M&A transactions takes root in good strategy. This chapter explores the role of strategy in deciding to grow by acquisition or restructure the firm. Strategy picks positions and capabilities. Analysis of positions and capabilities using a variety of tools outlined here should underpin the effort to profile your firm’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT).

M&A is one of the tactical instruments of strategy. This chapter outlines the variety of alternatives by which the firm could grow inorganically, ranging across contractual agreements, alliances, joint ventures, minority investments, acquisitions, and mergers. The choice among these alternatives is driven by at least three considerations: the benefits from relatedness of the target business to the core of the acquirer, the need for control, and the need to manage risk.

Restructuring activity is a significant source of M&A activity: one-quarter to one-third of all deals annually are divestitures by other firms. But divestiture is only one of the tactical instruments of a strategy of restructuring. This chapter outlines other alternatives, including liquidations, minority investments, spin-offs, carve-outs, split-offs, and tracking stock. (Financial restructurings are reserved for discussion in Chapter 13.) The selection among the various tactical alternatives will be driven by the relatedness of the unit to the core of the parent, the need for control, and whether the unit can survive as an independent entity.

The survey of research in this chapter suggests that restructuring creates value: Divestiture, spin-offs, carve-outs, and tracking stock are associated with significant positive returns at the announcement of those transactions.

However, the costs and benefits of a strategy of diversification remain unsettled. That diversification destroys value is the conventional wisdom in 2003, but the latest research challenges its certainty. This suggests that the practitioner should think critically about blanket assertions about the value of a strategy of diversification or focus. Future research will likely give a more contingent explanation, such as “diversification pays in these circumstances.” In the interim, it is too early to tell.

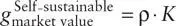

APPENDIX 6.1 A Critical Look at the Self-Sustainable Rate of Growth Concept and Formulas

The self-sustainable growth rate (SSGR) is the maximum rate at which a firm can grow without sales of new common equity. A firm that has a high SSGR relative to its targeted growth rate can execute its business strategy without having to dilute the interests of existing shareholders, submit its plans and intentions to the scrutiny of a stock offering, and incur the relatively high costs of stock issuance. Also, a firm that has a high SSGR relative to its competitors is bound to have some strategic advantage in exploiting the random flow of growth opportunities that come to every industry. Regardless of the popularity of this concept, the financial adviser and analyst must understand its possible application and limitations in order to put it to best use.

BEGINNINGS: A FOCUS ON VALUE

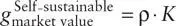

The interest in self-sustainable growth had its origins in the work of two academicians, Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani (1961) (M&M), who asked the question: At what rate will the market value of the firm grow? They argued that the only kind of growth on which operating managers should focus is growth of value because any of the other bases of growth (e.g., sales or assets) are flawed guides 16 for corporate policy; only growth of market value was consistent with an interest in value creation . M&M showed that the growth rate in market value is simply the product of two variables: the internal rate of return (IRR) of expected future cash flows, and the rate of reinvestment of that cash flow back into the firm.

(1)

Here K is the reinvestment rate of the cash flows, and ρ (or “rho,” a Greek letter) is the IRR of cash flows. The virtue of the M&M growth rate model is that it is economically correct: (1) it focuses on cash flow; and (2) it takes into account the time value of an entire stream of cash. The formula is deceptively simple: Whether the firm can reinvest in the same activities that produce a given IRR depends on a wide range of strategic assumptions such as the rate of technological change, the length of a product life cycle, or the persistence of competitive advantage. In short, the application of this model takes careful thought.

Читать дальше