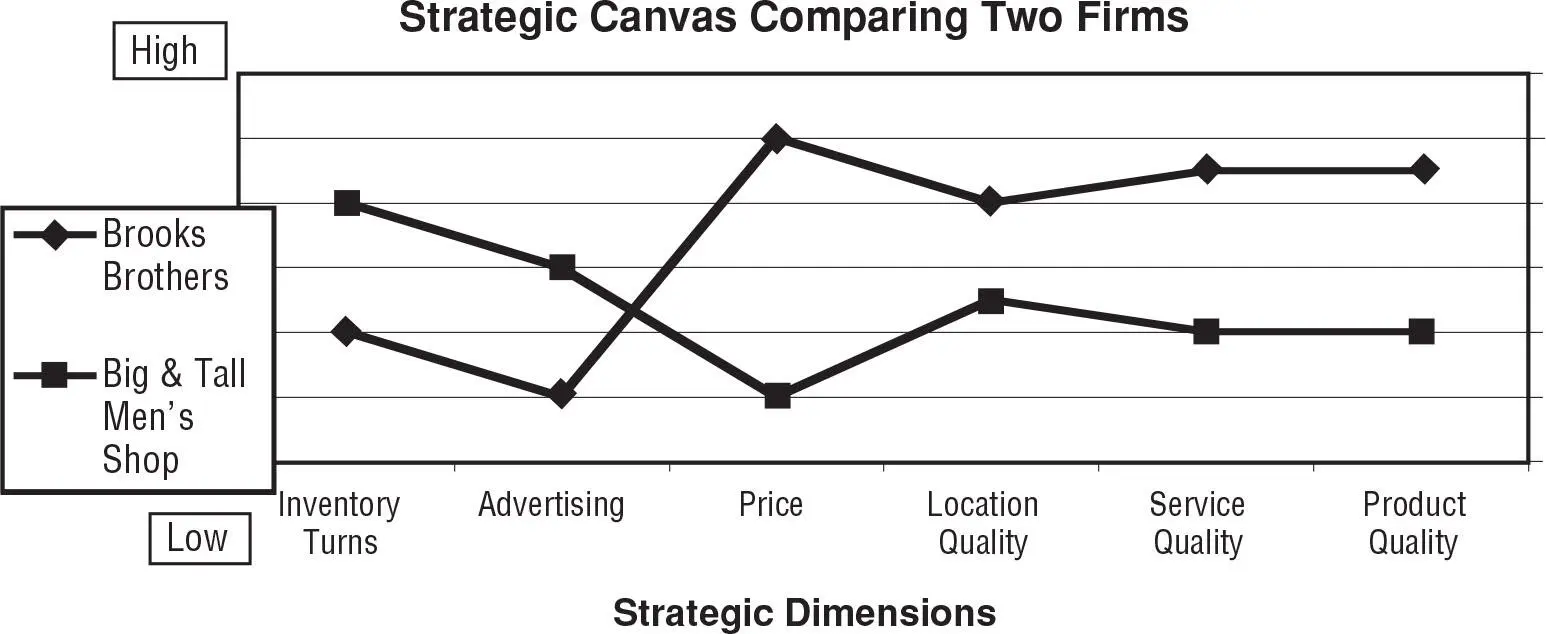

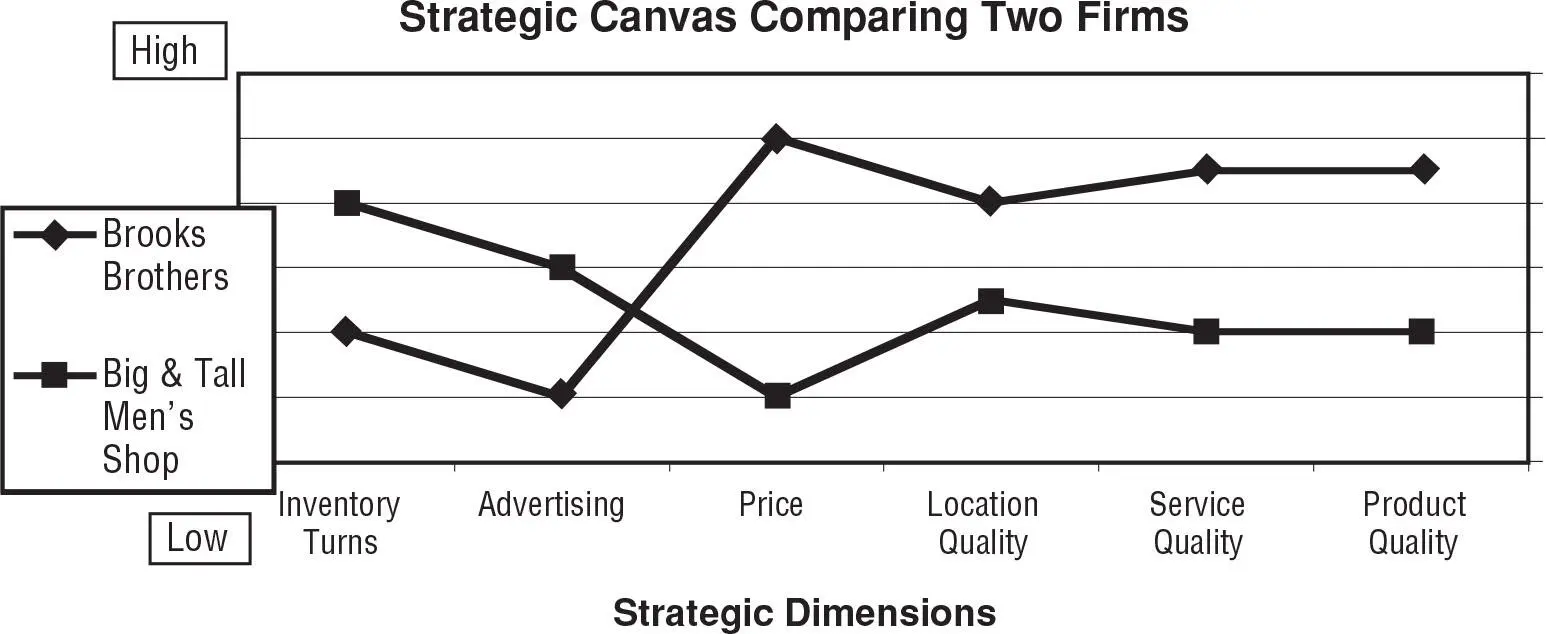

| Strategic Criteria for Comparison |

Brooks Brothers |

Big & Tall Men’s Shop |

| Product quality |

4.5 |

2.0 |

| Service quality |

4.5 |

2.0 |

| Location quality |

4.0 |

2.5 |

| Price |

5.0 |

1.0 |

| Advertising |

1.0 |

3.0 |

| Inventory turns |

2.0 |

4.0 |

EXHIBIT 6.8 Illustration of Strategic Canvas

Source: Qualitative assessment based on author’s analysis.

EXHIBIT 6.9 Illustration of Attractiveness-Strength Matrix

| Industry Attractiveness |

Competitive Position of the Unit |

| Strong |

Average |

Weak |

| High |

Most attractive: Invest and build. |

|

Question mark: Assess unit’s profitability and prospects for improving position. |

| Medium |

|

Moderate: restructure to improve. |

|

| Low |

Question mark: Analyze long-term profitability and prospects for endgame |

|

Least attractive: Restructure or exit. |

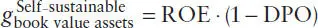

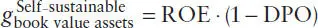

The resources of the firm will dictate the rate at which it can grow organically— this is the self-sustainable growth rate (SSGR) and is a test of fit between the firm’s current capabilities and its aspirations. In its simplest form, SSGR is determined by the firm’s return on equity (ROE) and dividend payout (DPO) ratio as follows:

This indicates that the maximum internally sustainable rate of asset growth will be a direct result of the firm’s profitability (ROE) and retention rate—(1 – DPO) or one less the percentage of earnings paid out in dividends. This rate can be compared to projected asset growth rates for the firm, its competitors, and its industry as a test of financial feasibility. Appendix 6.1discusses various models of the self-sustainable growth rate and illustrates their application.

Business Definitions Are Key

All of the analytic tools described in this chapter are judgment-intensive. They depend on proper definition of the business and the product being analyzed.

DEFINING THE BUSINESSThe industry position of a multibusiness or multiproduct firm, such as General Motors (GM), is less useful to analyze in the aggregate than are the positions of its individual products or business units. GM has relatively stronger and weaker segments. To aggregate them into a single assessment for GM yields none of the richness of the strategy problem GM faces. Salter and Weinhold (1979, page 268) argue that the level at which to define the unit of analysis is typically driven by strategic considerations (are there well-defined strategic sectors?), resources (are there special capabilities, patents, know-how, etc. that would justify defining a business in a certain way?), and organizational factors (how does the organization chart define business units, divisions, and sectors?).

DEFINING THE PEER GROUPFor instance, consider the example of the sporty cars segment (given in the strategic map of Exhibit 6.7). Is the relevant industry for the Porsche Boxster actually automobiles in general, or should it be two-seat European roadsters? Or transportation? Peers are those products or services that are reasonable substitutes in the customer’s mind. For instance, most brands of ketchup are peers in narrow definition—but considered in terms of competition in “sauces,” brands of ketchup, salsa, steak sauce, and gravy might be peers. One can aim to identify peer groups through competitive analysis, the use of focus groups, or the U.S. government’s “SIC” 3 code. As discussed elsewhere in this book, the selection of a peer group for comparison will have a huge impact on the insights to be derived.

Classic Successful Strategies

To illustrate the importance of positioning, Porter (1985) described three classic strategies that seemed to yield special competitive advantage:

1 Low-cost leadership. This seeks to create a sustainable cost advantage over competitors and is often seen in industries where the product or service is a commodity. The attainment of this leadership position permeates the firm and is achieved through focusing on cost containment, strict asset management, an annual budgeting process characterized by great scrutiny, tough negotiation of union and raw materials agreements, and low-overhead central office operations. The advantage of this strategy is that the low-cost leader can’t be undersold: This company will always win in a price war. A disadvantage of this strategy is that cost-minimization often requires a commitment to a particular product or process technology; such a commitment sacrifices flexibility. With technological innovation by competitors, this commitment can quickly turn from an advantage to a disadvantage.

2 Differentiation. This seeks to create a sustainable competitive advantage through distinguishing the firm or its products sufficiently to command a higher price and/or a strong customer franchise. It is seen in industries where customer demand is diverse and therefore unable to be satisfied with a commodity product. In pursuing this strategy, one must ask whether the pricing power achieved through differentiation is sufficient to compensate for the investment necessary to achieve it. Differentiation succeeds to the extent that it is hard to imitate and that it generates superior investment returns. Firms pursuing a differentiation strategy will focus on innovation, techniques of market segmentation, brand management, product quality, customer service, and warranties.

3 Focus or specialization. The focuser creates a competitive advantage by finding and dominating a market niche—there, the advantage springs from cost leadership or differentiation. This will be attractive where one can identify a niche of sufficient size to permit profitable and growing operations and where the firm has capabilities sufficient to serve demand. The disadvantage of a focus strategy is that the firm has all its eggs in one basket: Should the niche be successfully penetrated by a competitor, there will be no other market positions with which to mitigate the consequences.

In addition to defining these classic success strategies, Porter’s analysis raises an equally important point: Don’t get stuck in the middle. He argues that it is very difficult to establish a sustainable competitive advantage through hybrids of these approaches. By trying to be all things to all people, hybrids may become nothing to anyone. Skeptics of this point to Wal-Mart and Toyota, firms that successfully pursue cost leadership and the differentiation of products or services. Still, the difficulty of finding successful hybrids may justify them as the exception, rather than the rule.

EXPANSION BY INORGANIC GROWTH

M&A transactions should flow from the business strategy for the firm. Yet mergers and acquisitions are only part of the range of possible transactions a firm might contemplate in seeking to implement its strategy. Exhibit 6.10charts the variety of tactics and shows that they extend from transactions that grow or diversify the firm to transactions that restructure or focus the firm.

Читать дальше