This process echoes the genealogical analysis of Foucault, whose aim is to retrace the historical conditions of emergence of specific apparatuses of power. Foucault was largely influenced by Nietzsche’s own interpretation of history, as shown in his key text published in 1971 (Foucault 1971, pp. 1004–1024). Genealogy aims to ‘detect the singularity of events outside of any monotonous finality’ (Foucault 1971, p. 1004). It requires the meticulousness of knowledge, a large number of materials piled up, details, random beginnings, accidents, small deviations or complete reversals, errors, misjudgements, miscalculations. Foucault is said to have challenged ‘traditional history’, but according to his friend, the historian and philosopher Paul Veyne, Foucault believed only in the truth of the facts, of the countless historical facts that fill all the pages of his books; he was sceptical towards any universal concepts and started from the concrete practices of the state, and ordinary places of power rather than from general and well‐known ideas (Veyne 2008, p. 9, 19, 33). Interpreting history as a series of accidents and considering ‘that the forces at stake in history do not obey a destination or a mechanism but the randomness of the struggle’ (Foucault 1971, p. 1016) was quite unusual in the 1970s. Foucault’s genealogy was opposed to meta‐historical forms of writing (Foucault 1971, p. 1005), to historians who focus excessively on causal relationships (Veyne 2008, pp. 38–39), and to a history that does not take into account ordinary mechanisms of power (Foucault 1971, p. 1019). As David Garland explains (2014, p. 372), ‘genealogical analysis traces how contemporary practices and institutions emerged out of specific struggles, conflicts, alliances, and exercises of power, many of which are nowadays forgotten’. This book is an attempt to discover exercises of power, often located outside state power, sometimes within it.

In keeping with sociological traditions from its founding fathers to Michel Foucault and Paul Veyne, this book calls into question the antinomy between past and present. In an age of fragmented, hyper‐specialised and standardised knowledge, this choice reflects a scientific conviction – a unified conception of the social sciences including history – and a taste for intellectual and methodological cross‐pollination and comparative approaches. Such an endeavour entails articulating periods, and in this case, taking stock of the legacy from the colonial era and earlier periods, some of which are present in the forms of postcolonial power (Bayart and Bertrand 2006, p. 142). It means searching for the traces of the past in the present day (including the present of the historical actors) by making intelligible how ‘the things of the past are objectivised and crystallised in mental structures, in material things, in habitus’ (Noiriel 2010). This approach is characteristic of comparative historical sociology, which calls into question the opposition between idiographic and nomothetic disciplines (Bayart 1989; Déloye 1997) and of sociohistory, which emphasises the need to historicise social relationships viewed as products of power relationships that have become solidified, objectified, and naturalised over time (Noiriel 2012, 2010).

This dialogue between history and social sciences are central in the tradition of interdisciplinary knowledge in African studies (Balandier 1985 [1955]; Coquery‐Vidrovitch 1993; Ferguson 1999; Freund 2007; Mbembe and Nuttall 2004) which in some cases have entered into a productive dialogue with urban studies of the continent (Myers 2011; Simone and Pieterse 2017; Robinson 2006; Simone 2004). These have helped to include a more diverse historical experience in understanding the urban world and possible peculiarities of urban histories of the global south. Despite this tradition, a very specific use of history needs to be interrogated within some segments of urban studies. First, the historical experience is rarely based on a dialogue with the long tradition of African history. Second, while ethnographic methods have become central in so many disciplines, historical methods, i.e. the patient time‐consuming archival work and collection of oral and material sources, often seems to be marginal, leaving urban scholars with a second‐hand approach and a relative neglect of historical everyday life. Third, many scholars have not totally avoided a form of presentism. Presentism – or the rise of the category of the present until this comes a ubiquitous evidence – partly consists of reinterpreting the past according to this present (Hartog 2003, p. 223). A genealogical analysis is suggested as a possibility to avoid that risk while questioning the often‐marginal place devoted to the historicised dimension of urban life.

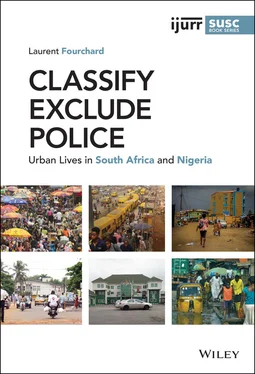

Practically, this means that there is a need to take contemporary and colonial periods seriously, i.e. systematically giving priority to primary sources with the same density of information. It has been of paramount importance to constitute a body of historical and ethnographical sources around shared questions. The historical sources include colonial, national and local archives consulted since 2000 at various sites in Nigeria (Ibadan, Kaduna, Enugu), South Africa (Pretoria, Cape Town, Johannesburg) and Great Britain (London, Oxford), and the local and national press archives in both countries, along with several dozen interviews with ‘elders’ on certain topics. The ethnographic materials come from a familiarisation with the environment of the neighbourhoods investigated in Cape Town, Ibadan and Lagos, repeated interviews with dozens of police organisation members, civil servants, union members and traders, together with participatory observation whenever possible (volunteer patrols in Cape Town, local governments in Ibadan and Lagos). 7 Rancière (1987) invites us to move between a word divided ‘between those who explain and those who listen’. As a French academic living and working in Nigeria and South Africa I was first and foremost educated by the many informants I had the chance to meet. Cross‐checking historical sources with ethnographical materials generated dialogue between literatures that usually do not communicate their findings and brought to light particular historical configurations that raised questions about changes in national policy (colonial/post‐colonial, military/post‐military, apartheid/post‐apartheid), which are often taken as the narrative starting point for want of longitudinal studies.

Many scholars have recommended provincialising Western urban analysis to achieve a more comprehensive view of global urbanisation, to give priority to a post‐colonial approach, and to call for a localisation of theoretical production (Robinson 2012; Roy 2011). If this book explores colonial and postcolonial history to figure out a peculiar historicity that may not fit a ready‐made definition of the urban, my aim is not to take part in developing a ‘Southern theory’ that would abstract from, circumvent or challenge ‘Western thought’. I prefer to read academics promoting Southern theory as cultural intermediaries who have raised these issues precisely because they have knowledge in different fields and different academic institutions (northern and southern). James Ferguson reminds us that ‘Thinking does not mean thinking from a single point of view, but thinking from more than one point of view at the same time’ (Ferguson 2012), a comment made in reference to Jean and Jane Comaroff who, like many ‘intellectuals of the South’, have positioned themselves in the space between them (Comaroff and Comaroff 2012).

I have adopted a similar approach in exploring this space between different academic traditions. For historical reasons, African universities are too often in a subaltern position in the production of knowledge that has received worldwide audience in the social sciences. A first step towards rebalancing this unequal production is to use the considerable and often neglected research produced in African universities. There is a long tradition of research in South African and Nigerian universities not always exposed in urban studies journals but which constitute the fundamental basis of this book. To produce new knowledge and new facts on urban Africa is another necessary step, not a technical point but a need for an exhaustive empirical research for which not abundant available data pre‐existed for a number of issues (Pieterse and Parnell 2016). This is also an epistemological choice situated in a grounded theory that provides theoretical insights based on empirical data (Glaser and Strauss 1967) that are necessarily provisional and revisable (Robinson and Roy 2016) and only possible through a constant process of exploring the tiny minutiae of urban life (Simone and Pieterse 2017).

Читать дальше