4.3 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

4.4 Conclusion

4.5 References

5 Periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Clinical evidence

5.3 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

5.4 Conclusion

5.5 Acknowledgement

5.6 References

6 Periodontitis and respiratory diseases

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Clinical evidence

6.3 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

6.4 Conclusion

6.5 Acknowledgement

6.6 References

7 Periodontitis, pregnancy and fertility

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Clinical evidence

7.3 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

7.4 Effect of pregnancy on periodontal tissues

7.5 Conclusion

7.6 Acknowledgement

7.7 References

8 Periodontitis and malignancy

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Clinical evidence

8.3 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

8.4 Conclusion

8.5 References

9 Periodontitis and neurodegenerative diseases

9.1 Introduction

9.2 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

9.3 Clinical evidence

9.4 Conclusion

9.5 References

10 Periodontitis, stress and depression

10.1 Introduction

10.2 Clinical evidence

10.3 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

10.4 Conclusion

10.5 References

11 Periodontitis and autoimmunity

11.1 Introduction

11.2 Cellular and molecular mechanisms

11.3 Clinical evidence

11.4 Conclusion

11.5 References

Figure source directory

Introduction

Josefine Hirschfeld and Iain L. C. Chapple

Periodontitis is a highly prevalent chronic inflammatory disease that impacts 45% to 50% of adults worldwide, with severe disease affecting 7.4% 1to 11.2% 2. The global incidence of severe periodontitis in 2015 was 6 million, accounting for 3.5 million disability associated life years (DALYs, a measure of disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to morbidity), compared with 1.7 million DALYs for untreated caries in adult teeth; more than any other oral disease 1. Moreover, the indirect cost to the global economy in 2015 of severe periodontitis was estimated at US $54 billion in productivity losses 3and the human cost is also significant in terms of reduced nutrition, social confidence and oral health-related quality of life. Periodontitis prevalence increases with age, with a steep incline between the third and fourth decades of life. Due to the growing world population, associated with an increasing life expectancy and a decrease in the prevalence of caries-related tooth loss in many countries 1, the burden of periodontitis is expected to increase.

Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic plaque biofilms and characterised by progressive destruction of the tooth-supporting tissues. Its primary features are presence of periodontal pocketing and radiographically assessed alveolar bone loss, and can also include signs of gingival inflammation such as redness, swelling and bleeding of the gingiva. Periodontitis is a major public health problem due to its high prevalence, and because it often leads to tooth loss when left untreated. This can result in reduced chewing function and aesthetics, and can further exacerbate oral pathology by leading to pathological tooth migration and occlusal trauma as well as periodontal–endodontic lesions. Therefore, periodontitis directly impairs quality of life 4.

Many aspects of the pathophysiology of this inflammatory condition have been characterised. It is recognised that periodontitis has multiple component causes, which when combined in each individual can exceed a threshold for disease initiation 5. Examples include:

● an aberrant host immune-inflammatory response to the dental plaque biofilm

● dysbiosis within the biofilm, which contains higher proportions of Gram-negative, anaerobic and facultative bacteria and is microbially less diverse than a healthy biofilm

● genetic and epigenetic factors affecting immune responses and tissue homeostasis

● older age, leading to immune senescence and consequent hyper-inflammatory responses, termed ‘inflammaging’

● modifiable lifestyle factors such as suboptimal oral hygiene, smoking, high stress levels and diets high in refined sugars and low in antioxidant micronutrients

● certain systemic conditions, which affect the immune system and which are discussed in this book.

Environmental factors may also contribute to the onset and progression of periodontitis, but these are currently less well understood. The dysregulated immune reactions ultimately lead to host-mediated damage and breakdown of the periodontal tissues including the alveolar bone. Clinical phenotypes may vary, with some patients presenting with severe periodontal breakdown at a relative young age.

Importantly, there is now abundant evidence that untreated periodontitis promotes the translocation of dental plaque-derived microorganisms, their antigens and certain metabolic components into the circulation, where they may elicit systemic inflammation via an acute-phase response and oxidative stress. This systemic dissemination of antigens and inflammatory mediators has been proposed to form the basis of the association between periodontitis and mortality and also with several systemic non-communicable diseases (NCDs), in conjunction with other mechanisms specific to those diseases 6. Numerous clinical and experimental studies have been undertaken in recent decades to better define the association between periodontitis and several systemic NCDs. However, these studies differ markedly in design and quality. In some clinical studies, inconsistent use of case definitions of disease, insufficient control of biases and small sample sizes render results difficult to interpret. Moreover, changes in disease classification systems make comparisons between studies published over several decades challenging. However, the new classification system of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions 7, as well as recently updated case definitions for periodontitis 8will help to create greater consistency in clinical periodontal research. Furthermore, the advent of international standards and guidelines for conducting and reporting studies has introduced more consistency and clarity and has improved the quality of those studies adhering to them. Some examples are PRISMA for meta-analyses, CONSORT or STROBE for clinical studies, ARRIVE for animal studies 9and MIQE or MIAPE for experimental ex vivo studies 10.

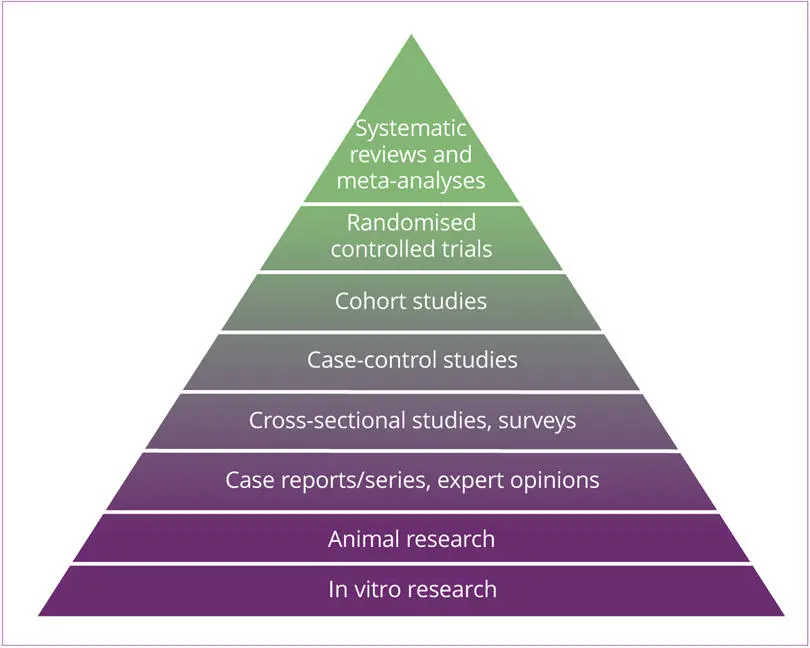

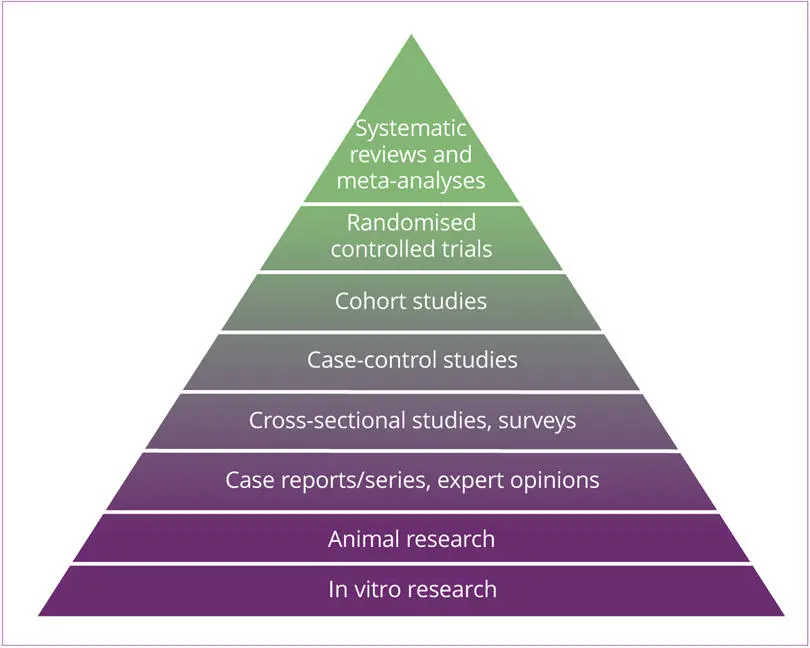

Prior to reading this book, it is important to consider certain principles. First is the principle of evidence-based medicine, which acknowledges that a hierarchy of evidence exists 11. This helps practising clinicians and researchers appraise literature and apply evidence to their work, based on the relative strengths and weaknesses of individual study designs. This hierarchy can be depicted as a pyramid, often referred as to the ‘evidence-based medicine pyramid’ (Fig 0-1). The pyramid is divided into levels, where each represents a different type of study design and corresponds to increasing rigour, quality and reliability of the results, and also to higher costs of conducting the relevant studies.

Fig 0-1 Evidence-based medicine pyramid.

The first three levels of the pyramid provide the foundation of knowledge. This background information is important and helpful, but can be heavily influenced by beliefs, opinions and even political views. The top of the pyramid suggests a lower risk of statistical error and bias from confounding variables. Cross-sectional and case-control studies represent the first stage of testing an observation. These studies are conducted in the early stages of research to help identify variables that might be associated with a condition. One of the weaknesses of these designs is that there are often small sample sizes and they are usually non-randomised. The next evidence level is that of prospective cohort studies, which follow people, who are exposed to the suspected risk factor for a disease, over a period of time. Here, causality can be assessed, but cohort studies require large sample sizes and long follow-up times, making them more difficult to apply to diseases with a long latency, such as periodontitis, or for rare conditions. Large double-blind randomised controlled trials are the most reliable study designs and provide the strongest level of evidence for cause and effect relationships. However, these studies are expensive and can be ethically problematic.

Читать дальше

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)