Jelly Roll Morton’s music takes us to the transition from ragtime to jazz (originally jass). The word ragtime comes from “ragged time,” the fact that the right and left hands of the pianist play different tempos. Jass is a more mysterious term. Some theorize that it comes from “jasmine,” an inexpensive perfume supposedly favored by whores in New Orleans’ famed red‐light district, Storyville. The fact that “jass” and then “jazz” were African American slang terms for sexual intercourse lends some credibility to the theory. Jelly Roll always claimed that his nickname did not refer to any fondness for the pastry. It was, he boasted, his signature move in making love. His “Black Bottom Stomp” is a good example of early jazz. The Black Bottom was a popular dance of the day, one that openly proclaimed its origins in the African American community.

The emergence of the “modern young woman” and the increasing influence of African Americans on American culture were highly controversial aspects of a far more general set of changes – modernization.

1920 also marked several major transitions. According to the Census, for the first time a majority of Americans lived in cities. The census defined urban as any place with a population of 2,500, so many “cities” were actually small towns. Nonetheless, urbanization was quite real. Cities attracted residents because that was where people could find work, entertainment, and a kind of freedom. But cities could also be frightening. There was crime and corruption, temptations of all sorts. There was anonymity; some considered it a boon, others a bane.

Diversity flourished in cities. People spoke dozens of languages, practiced dozens of religions, ate scores of cuisines. In the biggest cities, like Chicago or Philadelphia, clubs openly catered to homosexuals. There were notorious neighborhoods, like the Bowery in New York, where tourists and natives alike could find ways of satisfying any appetite. There were theaters. Revivalist Billy Sunday claimed that more sinners fell because of the theater than from drinking.

Sunday’s discomfort with modernity was widely shared. We can see it in the battles over what he called “Old Time Religion” and the related struggles among Protestants over the “fundamentals.” We can see it in the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan. We can see it in the campaigns to censor films and plays. We can see it in the decade‐long controversy over the one‐piece bathing suit for women. We can see it in efforts to outlaw the teaching of evolution. The list of battles in an ongoing, seemingly unending, culture war goes on and on. We will look at these and several others.

Underlying the culture war lay a fundamental question: Whose country was this? One answer, supposedly based on scientific research, was offered by the “science” of eugenics.

The infant selected as the “most perfect baby” in the Panama Canal Zone by the Eugenics Society of America. “Beautiful Baby” and “Fitter Family” contests were very popular during the 1920s and 1930s. At state fairs, for example, the Eugenics Society would set up exhibits at which visitors could answer questionnaires that would reveal their family’s “fitness.” In addition to getting their picture in the local newspaper, the winning family gained the assurance that it was among nature’s elite. In fact, any family scoring highly enough received a medal proclaiming, “Yea, I have a goodly heritage.”

Source: Truman State University.

Crime, insanity, mental defects, alcoholism, indigence, on one hand, were all products of “bad heredity.” Intelligence, industriousness, moral probity, on the other hand, were all products of a “goodly heritage.” There was a crisis confronting America because too many of those with bad genes were having too many babies, while those with good genes were having too few. Madison Grant, one of the most effective spokespeople for the movement, described this as The Passing of the Great Race (1916) in his best‐selling book. Lothrop Stoddard, for whose best‐seller Grant wrote an introduction, called it The Rising Tide of Color against White Supremacy (1920).

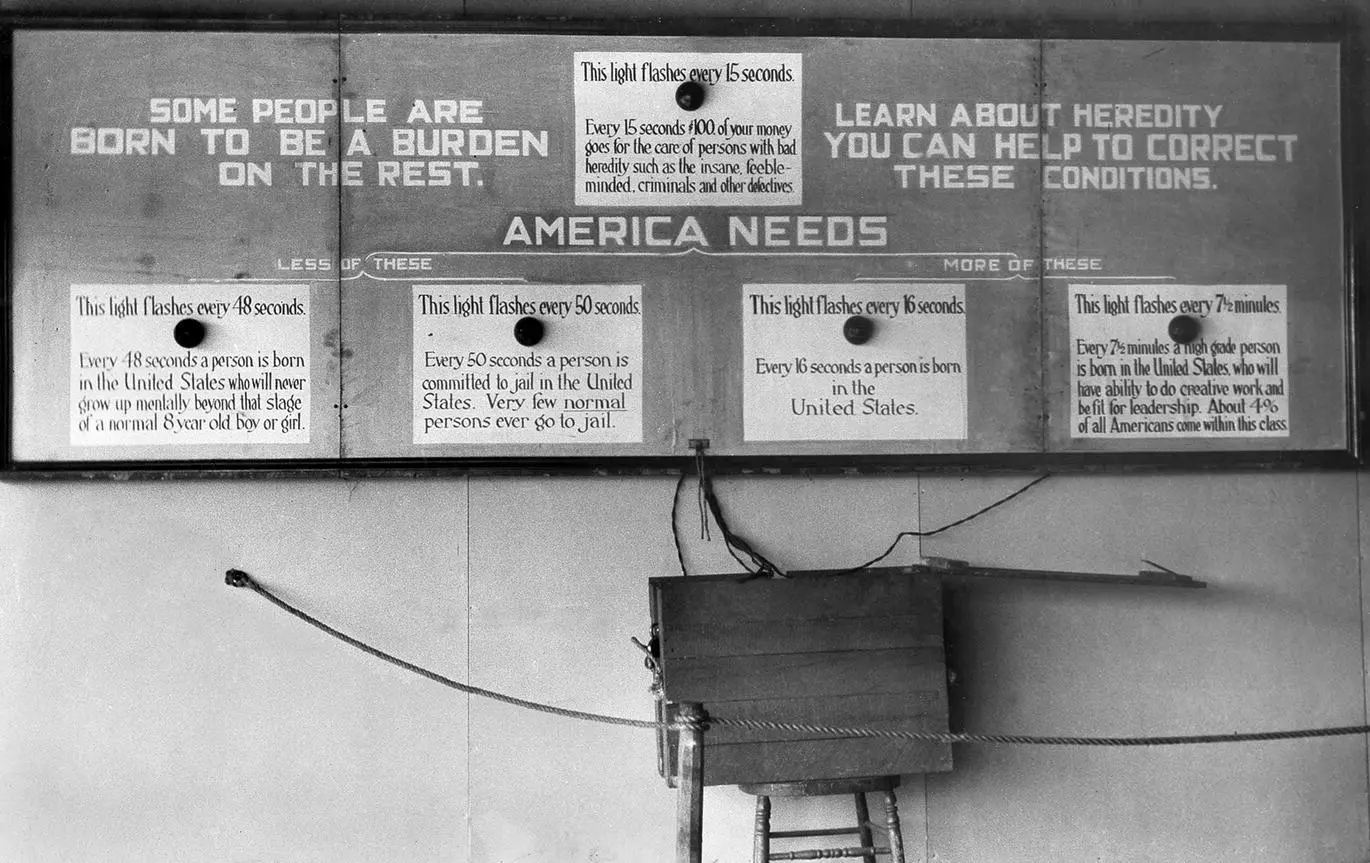

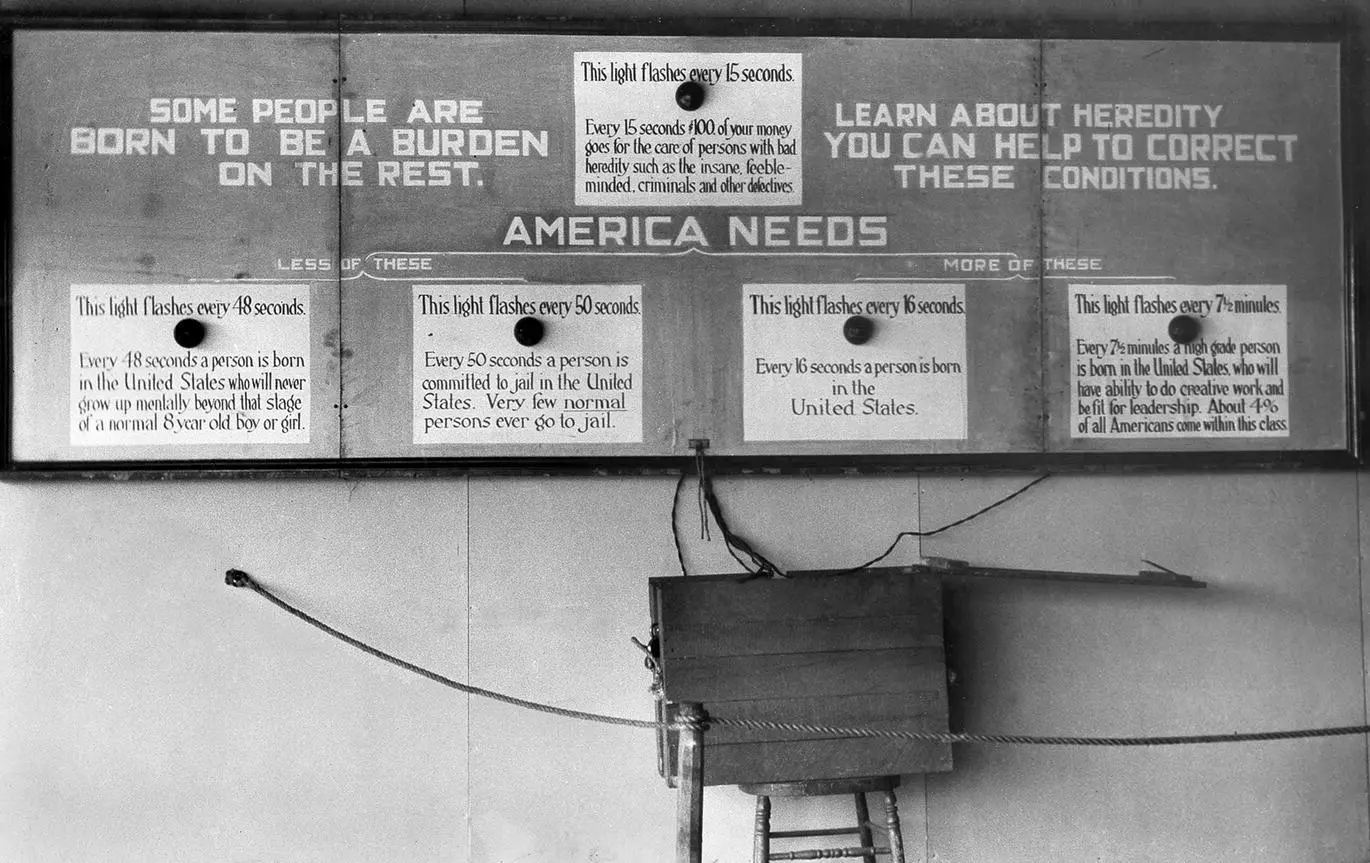

Eugenics exhibits typically used “flashing lights” to make the movement’s central points. “Some People Are Born to Be a Burden on the Rest,” the exhibit proclaimed. Every fifteen seconds a light flashed to mark the $100 in tax money spent on the insane, the feeble‐minded, criminals, and “other defectives” with “bad heredity.” Another light flashed every sixteen seconds. That was how often a baby was born in the United States. Few of these were perfect, however. Every forty‐eight seconds a light flashed, for the frequency of babies born who would grow up with the mental age of eight or lower. Every fifty seconds another light flashed. This was the frequency with which Americans went to jail. “Very few normal people ever go to jail,” the society insisted. At the far right was a light that flashed every seven and one‐half minutes. This marked the birth of a “high grade person who will have the ability to do creative work and be fit for leadership.” Only 4% of the American population, the society calculated, fell into this category.

Eugenics exhibits typically used “flashing lights” to make the movement’s central points. “Some People Are Born to Be a Burden on the Rest,” the exhibit proclaimed. Every fifteen seconds a light flashed to mark the $100 in tax money spent on the insane, the feeble‐minded, criminals, and “other defectives” with “bad heredity.” Another light flashed every sixteen seconds. That was how often a baby was born in the United States. Few of these were perfect, however. Every forty‐eight seconds a light flashed, for the frequency of babies born who would grow up with the mental age of eight or lower. Every fifty seconds another light flashed. This was the frequency with which Americans went to jail. “Very few normal people ever go to jail,” the society insisted. At the far right was a light that flashed every seven and one‐half minutes. This marked the birth of a “high grade person who will have the ability to do creative work and be fit for leadership.” Only 4% of the American population, the society calculated, fell into this category.

Eugenics activists, as both titles demonstrate, asserted a paradoxical message. Members of the “great race,” i.e., people of northern and western European backgrounds (with the noteworthy exception of Irish Catholics), were threatened by the proliferation of those, in the words of University of Wisconsin sociologist E.A. Ross, “whom evolution has left behind.” But how could the less fit possibly endanger the more fit? Wasn’t the story of evolution “the survival of the fittest”? No, according to eugenicists. They based that “no” on two sorts of arguments. Both began with the interference of humans in the workings of natural selection. Advanced societies no longer allowed the less fit to die. Instead, charitable organizations and the state intervened to protect those with various disabilities with the consequence that the less fit could successfully reproduce. But this did not explain why the members of the “great race” had declining birth rates. Once again, the answer had to do with human intervention in the natural process of selection. In comparatively primitive societies, up to and including the American colonies, children were economic assets. But, with the emergence of modern industrial societies, children became more and more clearly drains on family well‐being. Members of these advanced societies had fewer children. Immigrants, coming from less advanced societies, continued to have large families. So did people in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Hence the “rising tide” with its threat to “white supremacy.”

Eugenicists did not condemn these human interferences, however much they decried the consequences. Instead, they made “the human direction of evolution” the cornerstone of their movement. No longer should we allow nature to select human traits; having already intruded upon the process, we should continue to do so but in a scientific manner. Here is how the Eugenics Record Office at the Cold Spring Harbor Biological Laboratory phrased it in 1927: “Eugenics Seeks to Improve the Natural, Physical, Mental and Temperamental Qualities of the Human Family.” Source: American Philosophical Society. Noncomercial, educational use only.

Читать дальше

Eugenics exhibits typically used “flashing lights” to make the movement’s central points. “Some People Are Born to Be a Burden on the Rest,” the exhibit proclaimed. Every fifteen seconds a light flashed to mark the $100 in tax money spent on the insane, the feeble‐minded, criminals, and “other defectives” with “bad heredity.” Another light flashed every sixteen seconds. That was how often a baby was born in the United States. Few of these were perfect, however. Every forty‐eight seconds a light flashed, for the frequency of babies born who would grow up with the mental age of eight or lower. Every fifty seconds another light flashed. This was the frequency with which Americans went to jail. “Very few normal people ever go to jail,” the society insisted. At the far right was a light that flashed every seven and one‐half minutes. This marked the birth of a “high grade person who will have the ability to do creative work and be fit for leadership.” Only 4% of the American population, the society calculated, fell into this category.

Eugenics exhibits typically used “flashing lights” to make the movement’s central points. “Some People Are Born to Be a Burden on the Rest,” the exhibit proclaimed. Every fifteen seconds a light flashed to mark the $100 in tax money spent on the insane, the feeble‐minded, criminals, and “other defectives” with “bad heredity.” Another light flashed every sixteen seconds. That was how often a baby was born in the United States. Few of these were perfect, however. Every forty‐eight seconds a light flashed, for the frequency of babies born who would grow up with the mental age of eight or lower. Every fifty seconds another light flashed. This was the frequency with which Americans went to jail. “Very few normal people ever go to jail,” the society insisted. At the far right was a light that flashed every seven and one‐half minutes. This marked the birth of a “high grade person who will have the ability to do creative work and be fit for leadership.” Only 4% of the American population, the society calculated, fell into this category.