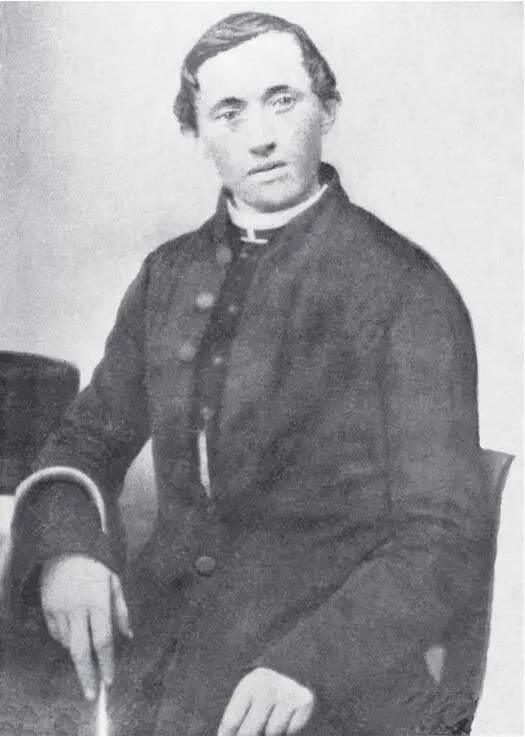

Before we follow the newly ordained priest to his first assignment, it may be well to pause for a brief review. It is based on the reminiscences which Fessler from Bregrenz, one of Wendelin’s classmates shared in 1888 on the occasion of their 25th anniversary of ordination. Fessler wrote:

“Pfanner was always serious about his studies. He excelled in Maths. I would like to illustrate his simplicity and self-control by referring to something he once said to us when we criticized a certain dish: ‘What does it matter how it is prepared as long as it is edible? Eat what is set before you!’ – While we were at the seminary, he was several times asked to mediate between rivalling friends and classmates. We came to appreciate his astute, practical mind, his clear vision and exquisite tact whenever he dealt with a sensitive issue.”

The editor of an 1888 commemorative brochure in honour of Abbot Francis expressed similar sentiments. According to him, the abbot was even as a youth known “to be diligent, industrious, solidly grounded in faith and morals, above board in every respect, opposed to evil in any shape and form, and fearless in expressing an opinion when it was called for. A good speaker and excellent mediator, he knew no regard for persons when he brought warring parties to terms. His faith was not shaken; neither did he change his mind once it was made up. Not given to making big or many words, he did study the theory of a proposition before he tabled it.”

II.

Parish Priest. Confessor to Sisters and Convicts

Pastoral Ministry in Vorarlberg, Confessor in Croatia

Four weeks after celebrating his first Mass, the new priest Wendelin Pfanner entered the pastoral ministry in Haselstauden near Dornbirn, Vorarlberg. Not used to speaking in public, he was shocked to hear his voice when he spoke from the pulpit for the first time, because “I had never before heard my voice echo back to me”. He remembered the advice of his professor in Pastoral Theology: “If you get stuck, pull all the stops! Take a quick look at your notes and continue!” Wendelin did not need it. Though the pulpit was new to him, he decided to speak freely from the beginning. But he carefully drafted every sermon. Unfortunately, he destroyed his notes as he did most other private papers.

Wendelin’s father considered it an honour to see his son off by “taking a good load of furniture, bed linen and clothes” to Haselstauden, while the young priest, in the company of two clerics from the neighbourhood, followed by coach. Haselstauden, however, wrapped itself in silence. Pfanner was not welcomed by the municipal administrator nor was a single villager on hand to help offload his “dowry”. Strange people, his father thought, shook his head and returned home on the spot.

The rectory seemed to have neither a kitchen nor a cook. The young priest did not see anyone until the following morning when, entering the church to say Mass, a grumbling old sacristan showed him round. But when he stood at the altar he was surprised that “the center aisle was filled with people. It was clear to me that they had not come so much to welcome me as to see who ‘the new one’ was.” How guarded, sceptical and suspicious these Haselstaudeners were! He wondered if he would ever be able to break down the wall behind which they were hiding. He did when typhoid broke out the following spring. It was a onetime opportunity to get to know them, and he seized it straight.

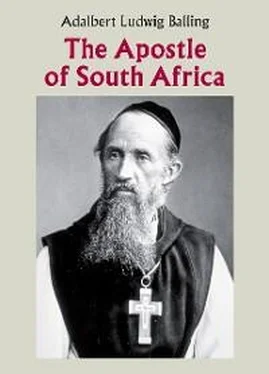

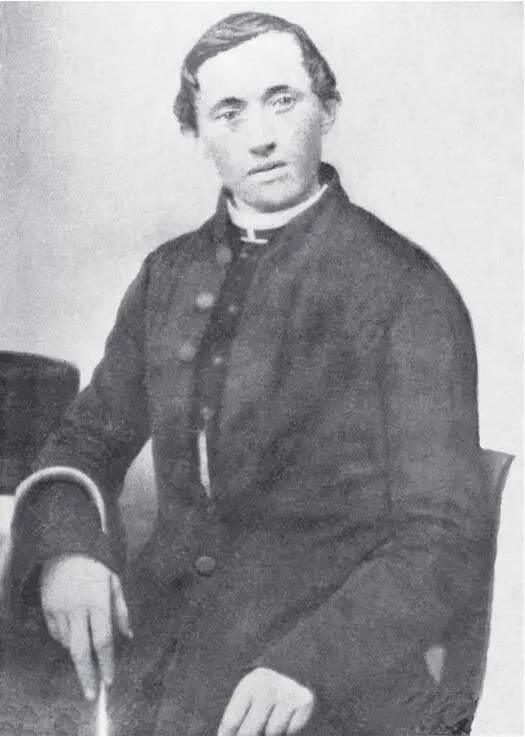

Wendelin Pfanner shortly after his Ordination to the Priesthood

Abbot Francis:

“I visited every affected family. People needed me because hardly anyone dared to go near them for fear of infection. They even told me how much they appreciated the visits of ‘the young gentleman’, as they called me. Their attitude towards me changed overnight. The church began to fill up, not now from curiosity but from a genuine desire to hear what I had to say.”

Biding his time and arming himself with much patience, young Fr. Pfanner won most of his parishioners back to the Church. He listened to them and learned to speak in a way they could understand. He instructed their children in the Faith, heard Confession and sought out the lapsed and critical. Occasionally, he read Leviticus to people who did not keep the Sunday holy, as for example, the innkeeper who when it was time for Sunday Mass sent his hired hands to work in the farm. He also persuaded two wealthy factory owners, both native Haselstaudeners, to donate stain glass windows for the parish church, Our Lady of the Visitation, which he wished to embellish. Their generosity bordered on a miracle. When twenty years later, as abbot of Mariannhill, he visited them, one remarked: “It would have been better if you had not become a Trappist. Why did you have to go so far away, first to these godforsaken Bosnians and then to the Hottentots in Africa? Haven’t we got Hottentots enough to convert?!” Nevertheless, he gave him a generous donation for the “black Hottentots”.

As for the “pagans of Haselstauden”, the young priest did all he could to strengthen their faith. For example, he invited excellent Redemptorist or Jesuit speakers to hold a parish mission. They did so with much success, the said factory owners allowing their employees to attend even on working days.

Whey Cures in Switzerland. Farewell to Haselstauden

Wendelin’s health deteriorated during his very first year in the ministry. This, though, was not the result of lack of care, because his sister Kreszentia, who had decided to stay single, was his housekeeper and looked very well after him. He developed a lung condition (TB?) and his doctor suggested that he drink whey at Gais in Canton Appenzell, Switzerland. The weeks he spent there were restful and relaxing but they did not bring about the desired cure. Abbot Francis: “The peaceful atmosphere and carefree time, the healthy air and diet probably helped me more than the whey.” As long as he had to preach, teach and hear Confessions there was little hope of recovery, leave alone a long life. So he decided to buy a burial site for himself and his sister just beside the Haselstauden church. For the rest, he served without sparing himself. In Anton Jochum, pastor of a neighbouring parish, he had a best friend and adviser. “When I was not sure about something, I consulted him and he always put me at ease, so that I saw my way again. I also gained a lot by listening to him explaining the Catechism and preaching. An excellent man, he had only one fault: he snuffed and that even during Mass! I drew his attention to it ever so cautiously but he just shrugged it off: “Alright, alright. Young men have fine manners! But you are right. Trouble is that I am too old to change.”

Though Fr. Pfanner was burdened with parochial duties he continued to mingle with people, his own family included. They could count on him. His father passed away in September 1856, but his stepmother lived for another twenty-four years. Her oldest son, Franz Xavier, married into a family at Gruenenbach in Bavaria, where as a young man he fell to his death from the threshing floor. When Wendelin’s twin brother Johann married outside the village, the Langen-Hub farmstead switched hands. Johann raised ten children. Nine were baptized by their priest uncle; the oldest was kicked by a horse and died in 1905.

In 1859, the vicar general of Vorarlberg sent Fr. Pfanner to Agram (Zagreb) in Croatia as confessor to a community of Mercy Sisters. Because these had originally come from Southern Tyrol, they were German speaking and needed a German-speaking priest. So Fr. Pfanner left Austria but not before inviting his unsuspecting parishioners to an auction sale of the cacti he had raised. They were a rare spectacle and for him a hobby the doctor had recommended as a pastime for the long winter months. He had a green thumb and in no time transformed the rectory into a sea of blossoms.

Читать дальше