The idea that virtus is only ever the product of discourse can hardly itself be challenged in language, since that challenge would only be subsumed into the agon that is verbal communication. And the conclusion we may want to draw from this is that any claim as to words’ “true meanings” can and should be challenged and deconstructed, that neither Sallust nor his readers are ever above the fray. But, on the other hand, the motion from the particular to the general, the reading of Sallust as operating at a more distant level of description than Cato, raises an alternative interpretation by at least gesturing towards a trajectory that distinguishes words from things. Sallust’s account of virtue may suggest its existence as well as pointing out how it is obscured in the very instant of its representation. The challenges of linguistic representation that begin when ideas move into time do not necessarily deny the existence or reality behind these representations. Batstone, pointing to a number of subtly observed contradictions in the Catiline ’s opening paragraph, describes the reader’s impression of knowing what Sallust must be saying, even as his language never clearly says it. 43I would put equal emphasis on the knowing what it must mean and balance a focus on the incapacities of speech with an awareness of the persistence of meaning, despite language.

But for the clearest evidence of the contemporary importance of the question precisely of whether virtus was a thing in itself or merely a word whose meaning depends on context, we must appropriately turn from Brutus the author to Brutus as a historical figure, observed and defined by others. Cassius Dio reports that as he prepared for suicide after the defeat at Philippi, Brutus quoted a couplet from the speech of a tragic Heracles.

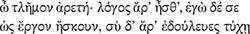

(Dio 47.49.2= trag. adesp . 374 Nauck= TrGF 1 88 F3)

(Dio 47.49.2= trag. adesp . 374 Nauck= TrGF 1 88 F3)

Oh shameless virtue, so you were a word after all. I worshipped you as a thing, but you were a slave to chance.

Because of its putative debunking of the notion of arete , the fragment has been read as a Cynic riposte to the stoic idealization of virtus . Thus Moles (1983a, 778–9) would derive the passage from contemporary pro-Caesarean polemic, condemning Brutus, the expert on virtus , for succumbing at the end to a very “unstoic” 44despair. Yet I think its meaning remains more open. Rather than suggesting that Brutus abandoned his principles just as he abandoned the actual “virtus” that might have led him to avoid suicide, it sympathetically shows him confronting an event that forces him—as many must have done in the course of the civil wars—to consider the basic premises for his actions. Whatever its source or interpretation, however, this version of Brutus’ last words has a threefold relevance for the interpretation of Sallustian virtus . Most importantly, it explicitly highlights the alternatives of a Batstone-style reading of virtus as a mere term of discourse, a logos , and the contrary assertion that virtus possesses some kind of objective reality outside of what people say about it. Second, the prompt to reevaluate virtus comes from an awareness of historical change. Within the quotation, virtus is made slave to the contingency that appears to govern the flow of events, to tyche , and of course it is the fact of a particular historical event, the battle of Philippi, that compels Brutus to doubt the reality of virtus . 45Finally, Brutus’ dramatic disillusionment with a philosophical ideal comes when he is presented with the most direct and terrible manifestation of his own subjection to temporality, the prospect of death.

I began with the image of two corpses, and it is appropriate that I end as well with dead bodies, for that is also what Sallust does. The historian’s final focus on the corpse of the protagonist stands as a stark alternative to the temporal and conceptual breadth of the opening, what all men always do. For Brutus too, as he was himself imagined in some historical narrative, the confrontation with death provokes his own tortured matching of general principles with undeniable events. It is the moment when words become things, when Brutus’ stoic preparation for death can or cannot be actualized, and when, in the case of Catiline, the wounds on his body take the place of the words he has spoken as a way of declaring that he was motivated by an inherited Roman morality, virtus , rather than the new avaritia and ambitio .

But death is equally the passage from events and things back to the words that are spoken about them, to virtus as an attribute dependent on others’ judgment rather than as something to be held, habetur ( Cat . 1.4). In Brutus’ case, his own deliberation about the dependence of virtus on fortune shifts to the audience for the historical narrative who must now decide whether Brutus’ act of speaking reveals his cowardice or virtus . Their decision can realize previous political alliances, or they can be emphatically set apart from politics: even an opponent may pity Brutus as a man. The perspective of the Catiline ’s opening, with its view of omnis homines , thus merges with the small view of Catiline as an individual in that both exclude the collective judgments of the state, of history as determined by the consensus of a group.

And so the focus in Sallust’s description begins with the Catilinarians’ bodies as semantic substitutes for their living presences—“for the very position which each while alive had fought to hold, his corpse was occupying even after death ( amissa anima ).” Notice how bodies here explicitly take the place of souls—unlike the philosophical ideal that connects them with eternity, in the real world the bodies are what we see, and the souls we can only conjecture. Yet in that moment of replacement a new perspective emerges, that of the audience whose identification of the corpses seems perhaps entirely contingent: some found a friend; others an enemy. This final demonstration of the dissolution of a collective response seems to make Catiline’s death a paradoxical victory for the small view. The partisanship he represents will be perpetuated by spectators who can only see from the perspective of their own relation to the corpse. For later readers, the moment in Senecan drama where Thyestes, who has similarly come to watch and consume, cries out to the king who has fed him his own children, “I recognize a brother” ( Th . 1006), may prompt a newly theatrical response to the scene where “gladness,” “grief,” “mourning,” and “joys” are “performed” variously through the army. This vantage point, admittedly way after the past, strongly intensifies the sense of revulsion that would make the audience retreat from the position of the internal spectator. But when Thyestes says he recognizes Atreus as a brother it also implies something about himself. As Atreus’ ruthless ambition reveals a kindred desire, so the recognition that Catiline’s troops were acting out desires common to all, especially to those who come for gain and gaze at forms, becomes a model for perceiving identity rather than difference. 46And perhaps those spectators’ recognition of cognati among the corpses even reflects a process of learning that changes their own assumptions about who the dead were. They have discovered public enemies ( hostes ) as relatives, or, looking with the eyes of the Roman community, they have recognized even relatives as personal enemies because they fought against the res publica . Or maybe people really are not like that at all. 47

Читать дальше

(Dio 47.49.2= trag. adesp . 374 Nauck= TrGF 1 88 F3)

(Dio 47.49.2= trag. adesp . 374 Nauck= TrGF 1 88 F3)