BLACK EARTH

RUSSIA AFTER THE FALL

ANDREW MEIER

‘There is depth to Andrew Meier’s portrait of Russia, but breadth as well. The treasures lie in his love for the country and the nuances that emerge from his encounters with Russian soldiers, politicians, pensioners and public servants’

Books of the Year, Economist

‘Written with curiosity, wit and sensitivity [Andrew Meier’s Black Earth is] a superb and erudite journey into the Russia he loves and knows better than virtually any other writer of his generation: it is the best work of Russian reportage since the fall of Communism’

SIMON SEBAG MONTEFIORE

‘The best piece of journalism written about Russia in English, and likely to remain so for a long time … The detail, knowledge and, above all, understanding which reside in this book remind us of how good journalism can be: how the first draft of history can be its freshest, its most poignant and its most alive … a record of extraordinary quality’

Glasgow Herald

‘Andrew Meier is not only a highly skilled journalist but also a remarkable listener … Black Earth is compelling and richly readable’

Mail on Sunday

‘A remarkable book. From the powerful first paragraph to the hopeful last it grips and grabs and stays with you. Highly recommended’

Ireland on Sunday

‘Impressive, building up to a many-layered portrait of post-Communist Russia … Meier has a genuine affection for the country and its people, which helps him to see beyond the one-dimensional image one gets from foreign newspaper reports’

Independent on Sunday

‘Moving … fascinating … Beautifully written and serves as a forceful reminder of quite how hard it will be to make real changes in Russia beyond the Moscow ring road’

Literary Review

‘[Meier] talks to gangsters, apparatchiks, intellectuals, oligarchs. He gives us not merely the buzz and glitter of Moscow and St Petersburg, but the squalid house-to-house fighting in Chechnya and – a rare experience – distant decaying Sakhalin beyond the Strait of Tartary’

Books of the Year, Times Literary Supplement

for Mia,

and for my parents

Cover

Title Page

Praise

Dedication

Prologue

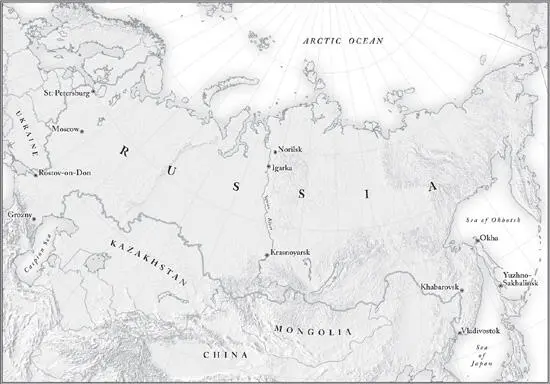

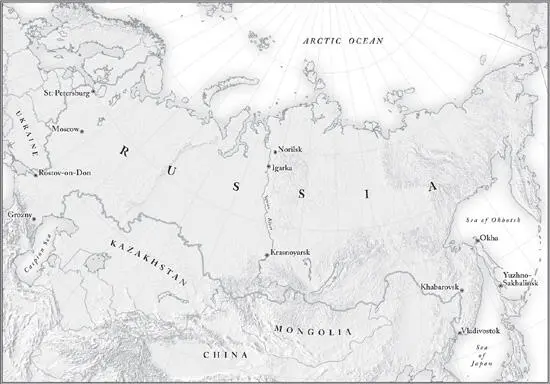

I. Moscow: Zero Gravity

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

II. South: To the Zone

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

III. North: To the Sixty-Ninth Parallel

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

IV. East: To the Breaking Point

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

V. West: The Skazka

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

VI. Moscow: “Everything Is Normal”

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features …

About the Author

Interview with Andrew Meier

Life at a Glance

About the Book

A Critical Eye

Afterword After Beslan

Russian Write Off

Read On

If You Loved This, You’ll Like …

To Find Out More, Andrew Meier Recommends …

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Author’s Note

Notes

Copyright

About the Publisher

HE HAD BEEN THEIR FIRST CHILD, the elder of two sons. After his death they had turned the darkest corner of the spartan living room into a shrine. A hazy black-and-white portrait, blown up beyond scale from an army ID, loomed above the reedy church candles and a thin bouquet of plastic flowers. They had draped a black ribbon over the photograph.

“When I served,” his father said, “I served the Motherland. ‘To serve with honor and dignity.’ That’s what they told us to do and that’s what I did. For twenty-eight years.”

Andrei Sazykin died in the summer of 1996. He was killed on the north-eastern edge of Grozny, before dawn broke on August 6, the parched day the rebels reclaimed their capital. The Chechens had swarmed back by the thousands. Seven other boys in his unit also fell that morning. Three weeks earlier Andrei had turned twenty.

For the Russian forces, the Sixth of August, as it became known, would live on. It would haunt them as a humiliation, the worst day of the war. For Andrei’s parents, Viktor and Valentina, it made no sense. They would sit in the dim light of their two-room apartment in Moscow and wonder how the Chechens had so easily retaken Grozny that day. Until the letters started to arrive. One after another, Andrei’s comrades began to write to his parents.

“And suddenly,” his father said, “everything came into this terrible perfect clarity.”

The letters were blunt.

“‘Your son served well,’” recited Viktor. He had read the words a thousand times, but he traced the lines with his forefinger. In his voice there were tears. “‘But he did not die in battle. He was sold down the river. We all were.’”

Valentina said the boys came to visit. They brought a video from their last days in Chechnya. It showed Russian officers, their shirts off in the severe heat of Grozny, playing backgammon with two Chechen fighters. They were smoking and drinking, all of them laughing.

“That was the afternoon on the day before Andrei died,” Viktor said. “The boys later pieced it together. There was no battle that morning. There was a deal. The Chechens paid their way through the checkpoints. The boys were slaughtered. And when the others went looking for the commanders, they were gone”

Months after their son’s death Viktor and Valentina brought a case, one of the first of its kind in Russia, against the Ministry of Defense. They sued to restore their boy’s honor and not, as the papers claimed, to get rich on compensation. They called his death a murder and vowed to seek punishment for those who killed him.

Several Augusts later, nearly five years to the day after their son died, I went to see them again. We had spoken in the intervening years. But I had never brought them the kind of news they craved, for I had failed to convince my editors that their son’s case was a story. I had, however, followed Viktor and Valentina as they waged their long campaign. They had started in their neighborhood court and fought all the way to Russia’s Supreme Court. They even won a hearing in the Constitutional Court. But at every station they lost.

Along the way Valentina lost her job. For two decades she had taught biology in the local school. Viktor meanwhile had been forced to get a job. He now worked twenty-four-hour shifts, four times a week, at an Interior Ministry hotel, a hostelry for visiting officers in Moscow. Their savings depleted, they had also lost their hope. All they had, said Valentina, was nashe gore (“our sorrow”).

Читать дальше