“Tell me,” Viktor said, fixing his eyes on mine. “Because I can’t understand it. But you must know. Can a country survive without a conscience?”

In the days that followed our last conversation, I left Moscow after a stay of five winters and six summers. I had, truth be told, lived in the country for most of the last decade. I had seen out the last years of the Soviet experiment and witnessed the heady birth of the “new Russia.” I had seen the romantic rise of Boris Yeltsin-and the wreckage his era wrought: the inglorious battle for the spoils of the ancient regime (an industrial fire sale of historic proportion), the military onslaught in Chechnya (the worst carnage in Russia since Stalingrad), and the rapid decline in nearly every index, social and economic, that the state took the trouble to record.

I had traveled far beyond the capital, to the distant corners of the old empire. I had lived for years in the remains of the Soviet state amid the millions of spectral dead souls who walked its ruins, as well as the rising new class of rent seekers, instant industrialists, and would-be entrepreneurs, who raced to accumulate and acquire, lest their new world vanish as quickly as the old. I had interviewed Politburo veterans and Gulag survivors, befriended oligarchs and philosophers. But I had no answer for Andrei’s parents. I could only tell them that I hoped to write a book – not only to record my travels across Russia’s length and breadth but, above all, to try to make sense of their plaintive question.

Vykhod est’! (“There Is a Way Out!”)

–Moscow metro slogan, 2001

IN THE OLD DAYS, before the breakneck final decade of the last century, before the end of empire and the epochal shift that followed in its wake, in the days when dissenters were dissidents and poets were prophets, when “abroad” meant Bulgaria, Budapest, or Cuba at best, when leather shoes and silk ties were not bought but “gotten,” when colleagues were “Comrades” and strangers “Citizens,” when HIV and heroin were exotic plagues born of bourgeois excess, when artists and soldiers pointed to ceilings and dropped their voices, when churches held archives and orphans, when lovers met in parks because apartments housed generations, when everyone professed to believe in the Party, the Collective, and Vodka but in truth trusted only Fate, God, and Vodka, I first came to Moscow.

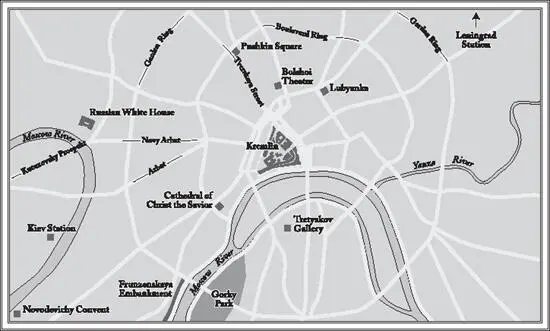

By the time I left, I had lived there longer than in any other city. But Moscow, like the country that surrounds it, eludes one. It defies measurement and loathes explanation, as if inherently ill disposed to definition. Longevity in Russia does not always yield understanding. Neither does intimacy guarantee knowledge. Nor does the first sensation of walking the city’s poplar-lined boulevards and great avenues of granite, that first sense of awe and astonishment at the fairy-tale world turned nightmare, ever seem to diminish.

First impressions in Moscow fortunately do not lie. The city is built on an inhuman scale. Everything is by design inconvenient for Homo sapiens . The streets are so vast crossing them requires a leap of faith. The cars do not stop for pedestrians; more often they accelerate. The streets are so broad one can traverse only beneath them, through dimly lit passageways that shelter the refugees of the new order: makeshift vendors who hawk everything from Swedish porn to Chinese bras; scruffy preteens cadging cigarettes and sniffing glue; hordes of babushkas who have fallen through the torn social safety net and are left to sell cigarettes and vodka in the cold; the displaced stranded by the host of unlovely little wars that raged along the edges of the old empire. And everywhere underground the stench of urine lingers with the acrid aroma of stewed cabbage and cheap tobacco.

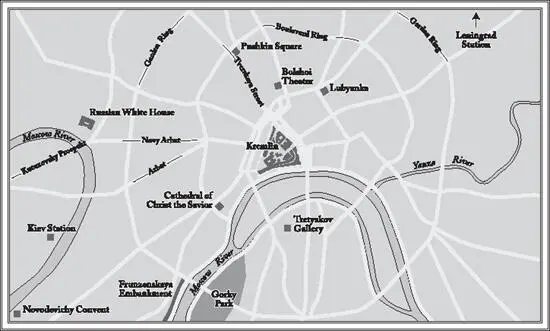

Aboveground the city seems to exist – as it did at its birth – to trade. Kiosks on nearly every corner, bazaars in every neighborhood. Even the outlying districts, more a part of the woods than the city, are overrun with feverish commerce. In the post-Soviet years, open-air wholesale markets, sprawling encampments of plastic tenting and cargo containers, lured tens of thousands each weekend. Here were the fruits of globalization, tinged inevitably with a Russian style: electronic and computer goods from the East and from the West, pirated software on CDs burned locally and on video, Hollywood blockbusters still unreleased in the States. The off-the-books trade united unlikely partners. A drug market sprouted one block from the Lubyanka, the once and present headquarters of the secret police, on a street where pensioners sold their prescriptions to hungry young addicts.

Slowly, too, the signs of the new opulence – the transfer of the state’s vast wealth into the hands of a chosen few – came to dominate Moscow’s implacable center. Vacant nineteenth-century mansions, the crumbling former residences of the prerevolutionary merchant class, became the ornate offices of new millionaires and billionaires, the men who soon took to calling themselves oligarchs. Even during the harshest years of the Communist era, Moscow had always been on the make. But in the mid-1990s, with the rise of powerful moguls like Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, and Vladimir Potanin, among a half dozen others, the Great Grab began. In the bedlam of the Yeltsin years, the profit margin grew into a gaudy obsession. “The primitive accumulation of capital” was what the oligarchs, remembering their Marx, called their thirst for the riches of the ancien régime .

This of course was “the New Moscow.” When I first stepped foot in the city in 1983, Moscow was grim and gray, a place of vast public spaces dominated by an eerie silence. It was the height of the age of Yuri Andropov, one of the last of the dour old men to rule the USSR. The Soviet war in Afghanistan was at its tragic height. I was then a nineteen-year-old undergraduate on a cheap one-week Sputnik tour. I had flown in from East Berlin with two dozen Bavarian high school students and, inexplicably, an older businessman from Buenos Aires who mesmerized the Kremlin guards with a new invention, a video camera.

My eyes glazed at the strange fairy-tale world. In the kaleidoscope of sounds and impressions, Moscow, it seemed, hosted another race on another planet. One encounter, above all the rest, remains indelible, fixed in the present. I sit on a low brick wall on a corner of Red Square. As I watch the crowds moving across the square, a young boy approaches. His name is Ivan. But I do not understand him when he tells me his age. He holds up ten fingers and folds down one pinkie. Nine, I understand. We cannot speak with each other. We only manage to establish two things. “ Lenin tut ,” Ivan says, pointing to the squat red granite mausoleum that sits across the cobbled square. “ I Mama tam .” (“Lenin is here. And my mama’s over there.”) He waves a hand to swat the air, pointing to an office that lies far beyond this great busied corner of Moscow. That afternoon I made a vow to myself: I would return to Russia only once I had learned the language.

Five years later I did. In 1988 I came back as a graduate student from Oxford to study for a term. I never expected, of course, that I would stay on in Moscow to witness the USSR during its final gasps. After Oxford, there was only one place I wanted to be, where I had to be. I told family and friends that I was making my way as a free-lance journalist. In truth I was searching for any excuse to stay in Moscow. I was in love.

Читать дальше