In the late 1940s and early 1950s the economic situation was still dire, with a lack of money everywhere in the country, while food was still rationed. Those were conditions that we can scarcely imagine today, and thank God we don’t have to. Fortunately or unfortunately, you don’t choose your way into life! Those were very hard times, but they are undeniably a part of my life, helping make me who I am today, and making it possible for me to lead the life I’ve lived. And to be honest, it’s been a pretty good life. I am firmly of the belief that our lives are already planned, even before we take matters into our own hands, this personal book of life having been written prior to our birth. If life was not easy in Scotland as a whole, it was even more difficult on Islay, but still uniquely beautiful. I would like to tell you a bit more about my childhood.

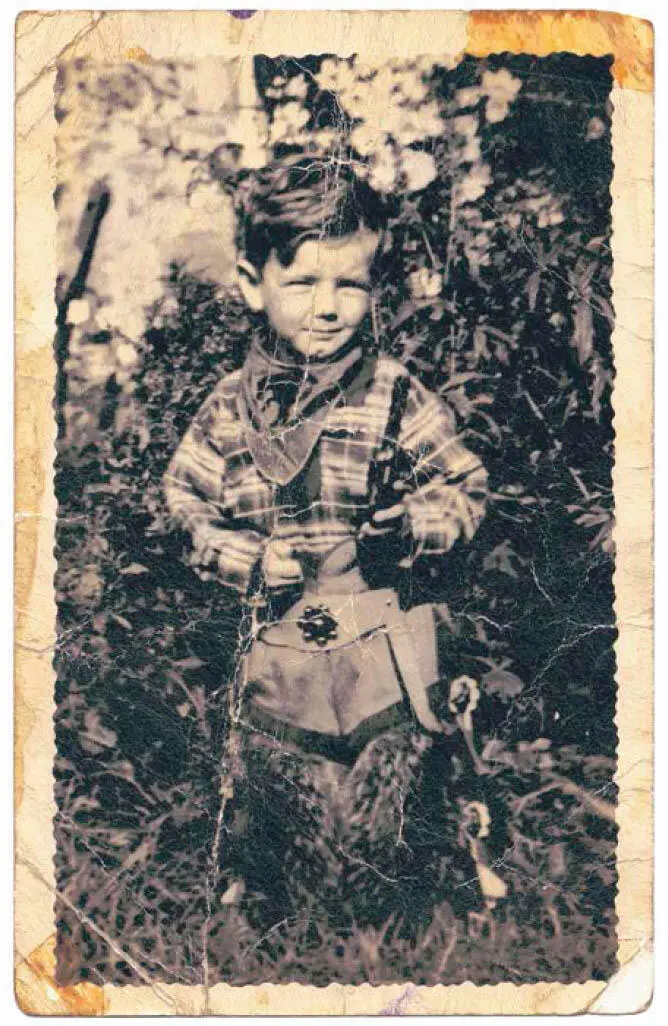

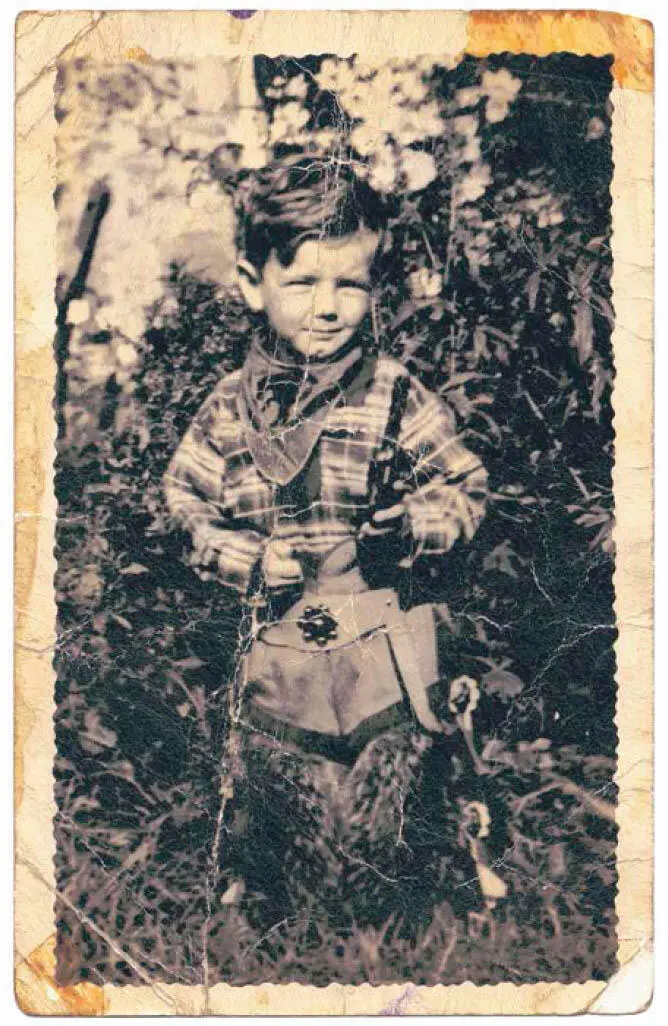

Jim at the age of about five.

At the centre of the island lies the beautiful village of Bowmore. Protecting and watching over everyone is a church perched at the highest point of the village, the only round church in the whole of Scotland. It was built in this shape in 1769 so that the devil could not hide in any corners. Unsurprisingly, the devil has never been sighted in Bowmore.

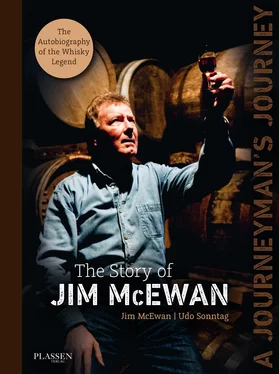

Jim’s birthplace.

My birthplace, at 7 Main Street, was about halfway between the church and Bowmore distillery, in a building that currently houses the Royal Bank of Scotland. That means there is a lot of money in the house today, but when I was born that was hardly the case. It was sorely lacking then. There were four families living in the building, each in very small flats. I lived on the top floor with my mother Margaret, who everyone called Peggy, and my grandmother Kate. Next door to us lived a woman with her son. On the ground floor, on the right, lived an elderly, retired woman, and a fisherman lived opposite. It was all quite crowded. Our small flat consisted simply of a kitchen-living room and two bedrooms in which my mother and grandmother slept. I usually slept on the sofa, because we couldn’t afford another bed. Poverty was part of our everyday lives. To keep us all warm, there was a small, coal-fired stove on which we also cooked. We had few, if any, luxuries, focussing solely on the essentials. However, we had a roof over our heads that we could call ‘home’, a safe place in which to live, and where we could eat and sleep.

Life in those days was much slower – not easier, just slower. Production in the distilleries had yet to resume, and in those war-torn times, life really demanded a lot. With hardly any jobs in the early 1950s, even we children had to do our bit in order to survive. I recall very clearly that we had special holidays at school, referred to as the ‘Potato Holidays’. This meant that all the children went out into the fields, in all weathers, at harvest time to pick potatoes. Outside all day, bending down, picking up and then carrying the heavy baskets together, it was pretty hard work for children, but it didn’t stop us from having some fun too. Every day we were dirty and covered in mud from top to bottom, for when it rained there was no slacking; the job had to be done. And there are many rainy days on Islay. However, we received a small wage, the equivalent of about 50 pence a day. It wasn’t much, but it was honestly earned and much needed income, on top of which, we were also given a sack of potatoes. In the evening, when we ate them together, they tasted even better. My mother and grandmother were great cooks, always able to make a great meal out of very little. Today, you really only know about all the hardship and poverty from old black-and-white films, yet life was anything but black-and-white. For us as children it was often very colourful. When I recall my childhood, what comes to mind most is what it meant to live on an island. Though today, regular ferry and air services provide the island with everything it needs, Islay was far less accessible back then. Sea links to Scotland’s western islands were served by the so-called puffers, coal-fired steamships, though modern for the time. I will tell you more about these ships later.

Bowmore harbour was the stomping ground for us kids, one of the best adventure playgrounds you could imagine. Of course, it was strictly forbidden to play there. “Don’t go to the harbour! If I see you on the raft, I’ll spank you and you’ll go straight to bed!” – was my mother’s clear message, but then, that was precisely the attraction. How I loved watching all the boats sail out in the mornings, after which they’d cast their nets and return with a rich catch. Every now and then a fisherman would take me out and let me help him with his work. To go out to sea, steering my way through the waters, was total freedom. For a small boy, the sea had no end, and how I wanted to sail out into the world, travel to foreign countries, and get to know of other, far-off cultures. With the sea as a gateway to the world, the fascination was there even then. As young pirates, we fought sea monsters, sailed the seven seas and captured many a well-laden frigate. Every day there was a new story to be experienced. You’d scarcely believe how many small fortresses, prisons, treasure chambers and dungeons are to be found in a small harbour, countless corners that captivated wee boys looking for adventure. Each of us knew where we could and could not go, but the forbidden areas were the most exciting. We were always looking towards the shore, where our parents might be standing, for you desperately wanted to avoid being caught exploring these banned zones. What you didn’t count on, however, was a state of affairs that rarely exists today: you didn’t just have one mother on the island, but several. “Jim McEwan! You know very well that you’re not allowed to do that – surely your mother told you that!” This exact sentence echoed through Bowmore, clearly and unmistakably from a wide variety of voices. Even though I didn’t like it at the time, it gave me a feeling of familiar security, knowing there was always someone looking out for you. On Islay it was the manifestation of a responsibility for others, back in a time before mobile phones. More than once, my mother pulled me off the raft, dragged me up Main Street by my ears, before giving me a slap or three and I was sent to bed without supper. However, when that happened, my ever-faithful ally was my beloved grandmother Kate. She would always tell my mother, “Let him be, he’s only a boy and he just wants to play like a boy. Come here son, here’s your supper.” Granny Kate understood me so well – though, of course, my mother understood too, but she was more concerned for my well-being.

Unfortunately, I never got to meet my grandfather. Though I’m sure he could have taught me a lot, I can only repeat what everyone who knew him said: John McEwan was a kind and gracious man, having lived a spectacular life. Like almost all male Ileachs, he went to sea, having hired out as a horse whisperer on a ship taking horses to Cuba. As a result, he was nicknamed ‘Cuba’. He always travelled below decks with the animals, calming them down whenever the seas became rough. On their passage, the horses undoubtedly learned Gaelic, for my grandfather spoke the language fluently. On his return to Islay, he found work as a maltman, a barley turner, in Bowmore distillery, and like almost all men of those days, he smoked a pipe. When I look at old photos of him, he was always to be seen with a pipe in his mouth. I loved that familiar smell of tobacco, but smoking eventually took its toll, and he died much too young from cancer of the throat. I missed my grandfather John very much, even though I never got to meet him.

Читать дальше