The dreadful news of the fate of the colony was borne to the philanthropists in England. But their faith in colonization stood as unblanched before the revelation as the Iron Duke at Waterloo. An association was formed under the name of "St. George's Bay," but afterwards took the name of the "Sierra Leone Company," with a capital stock of one million two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, with such humanitarians as Granville Sharp, Thornton, Wilberforce, and Clarkson among its directors. The object of the company was to push forward the work of colonization. One hundred Europeans landed at Sierra Leone in the month of February, 1792, and were followed in March by eleven hundred and thirty-one Negroes. A large number of them had served in the British army during the Revolutionary War in America, and, accepting the offer of the British Government, took land in this colony as a reward for services performed in the army. Another fever did its hateful work; and fifty or sixty Europeans, and many blacks, fell under its parching and consuming touch. 104Jealous feuds rent the survivors, and idleness palsied every nerve of industry in the colony. In 1794 a French squadron besieged the place, and the people sustained a loss of about two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Once more an effort was made to revive the place, and get its drowsy energies aroused in the discharge of necessary duties. Some little good began to show itself; but it was only the tender bud of promise, and was soon trampled under the remorseless heel of five hundred and fifty insurrectionary maroons from Jamaica and Nova Scotia.

The indifferent character of the colonists, and the hurtful touch of the climate, had almost discouraged the friends of the movement in England. It was now the year 1800. This vineyard planted by good men yielded "nothing but leaves." No industry had been developed, no substantial improvement had been made, and the future was veiled in harassing doubts and fears. The money of the company had almost all been expended. The company barely had the signs of organic life in it, but the light of a beautiful Christian faith had not gone out across the sea in stalwart old England. The founders of the colony believed that good management would make the enterprise succeed: so they looked about for a master hand to guide the affair. On the 8th of August, 1807, the colony was surrendered into the hands of the Crown, and was made an English colony. During the same year in which this transfer was made, Parliament declared the slave-trade piracy; and a naval squadron was stationed along the coast for the purpose of suppressing it. At the first, many colored people of good circumstances, feeling that they would be safe under the English flag, moved from the United States to Sierra Leone. But the chief source of supply of population was the captured slaves, who were always unloaded at this place. When the English Government took charge of Sierra Leone, the population was 2,000, the majority of whom were from the West Indies or Nova Scotia. In 1811 it was nearly 5,000; in 1820 it was 12,000; it 1833 it was 30,000; in 1835 it was 35,000; in 1844 it was 40,000; in 1869 it was 55,374, with but 129 white men. On the 31st of March, 1827, the slaves that had been captured and liberated by the English squadron numbered 11,878; of which there were 4,701 males above, and 1,875 under, fourteen years of age. There were 2,717 females above, and 1,517 under, the age of fourteen, besides 1,068 persons who settled in Freetown, working in the timber-trade.

With the dreadful scourge of slavery driven from the sea, the sanitary condition of the place greatly improved; and with a vigorous policy of order and education enforced, Sierra Leone began to bloom and blossom as a rose. When the slaver disappeared, the merchant-vessel came on her peaceful mission of commerce.

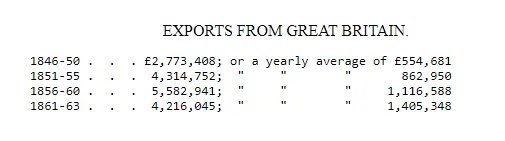

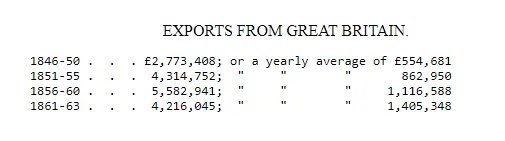

The annual trade-returns presented to Parliament show that the declared value of British and Irish produce and manufactures exported to the West Coast of Africa, arranged in periods of five years each, has been as follows:—

IMPORTS

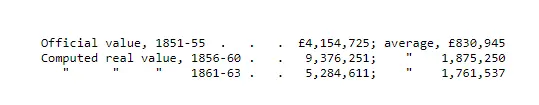

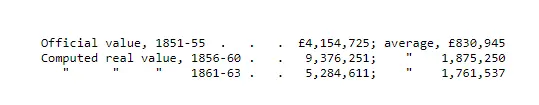

The same trade-returns show that the imports of African produce from the West Coast into Great Britain have been as follows. The "official value" is given before 1856, after that date the "computed real value" is given.

The value of African produce has decreased during the last few years in consequence of the discovery of the petroleum or rock-oil in America. In 1864 between four and five thousand bales of cotton were shipped to England.

It is to be borne in mind, that under the system which existed when Sierra Leone, the Gambia, and Gold Coast settlements were maintained for the promotion of the slave-trade, the lawful commerce was only £20,000 annually, and that now the amount of tonnage employed in carrying legal merchandise is greater than was ever engaged in carrying slaves. 105W. Winwood Reade visited Sierra Leone during the Rebellion in America; but, being somewhat prejudiced against the Negro, we do not expect any thing remarkably friendly. But we quote from him the view he took of the people he met there:—

"The inhabitants of the colony may be divided into four classes:—

"First, The street-venders, who cry cassada-cakes, palm-oil, pepper, pieces of beef, under such names, as agedee , aballa , akalaray , and which are therefore as unintelligible as the street-cries of London. This is the costermonger type.

"Second, The small market-people, who live in frame houses, sell nails, fish-hooks, tape, thread, ribbons, etc., and who work at handicrafts in a small way.

"Third, The shopkeepers, who inhabit frame houses on stone foundations, and within which one may see a sprinkling of mahogany, a small library of religious books, and an almost English atmosphere of comfort.

"Lastly, The liberated Africans of the highest grade, who occupy two-story stone houses enclosed all around by spacious piazzas, the rooms furnished with gaudy richness; and the whole their own property, being built from the proceeds of their … thrift."

When England abolished the slave-trade on the West Coast of Africa, Christianity arose with healing in her wings. Until slavery was abolished in this colony, missionary enterprises were abortive; but when the curse was put under the iron heel of British prohibition, the Lord did greatly bless the efforts of the missionary. The Episcopal Church—"the Church of England"—was the first on the ground in 1808; but it was some years before any great results were obtained. In 1832 this Church had 638 communicants, 294 candidates for baptism, 684 sabbath-school pupils, and 1,388 children in day-schools. This Church carried its missionary work beyond its borders to the tribes that were "sitting in darkness;" and in 1850 had built 54 seminaries and schools, had 6,600 pupils, 2,183 communicants, and 7,500 attendants on public worship. It is pleasant to record that out of 61 teachers, 56 were native Africans! In 1865 there were sixteen missionary societies along the West Coast of Africa. Seven were American, six English, two German, and one West-Indian. These societies maintained 104 European or American missionaries, had 110 mission-stations, 13,000 scholars, 236 schools, 19,000 registered communicants; representing a Christian population of 60,000 souls.

The Wesleyan Methodists began their work in 1811; and in 1831 they had two missionaries, 294 members in their churches, and 160 pupils in school. They extended their missions westward to the Gambia, and eastward toward Cape Coast Castle, Badagry, Abbeokuta, and Kumasi; and in this connection, in 1850, had 44 houses of worship, 13 out-stations, 42 day-schools, 97 teachers, 4,500 pupils in day and sabbath schools, 6,000 communicants, 560 on probation, and 14,600 in attendance on public worship. In 1850 the population of Sierra Leone was 45,000; of which 36,000 were Christians, against 1,734 Mohammedans.

Читать дальше