Cohen & Steers Senior Vice President and Global/U.S. Portfolio Manager Laurel Durkay – along with Senior Vice President and U.S. Senior Portfolio Manager Jason Yablon – gave some interesting insights on the subject in their September 2020 publication, “How REITs Benefit Asset Allocation.”

They noted, “REITs have historically served as effective diversifiers, as they tend to react to market conditions differently than other asset classes and businesses, potentially helping to smooth portfolio returns.”

They also wrote that “share aspects of both stocks and bonds – responding to economic growth like equities, but with yields and lease‐based cash flows that give them certain bond‐like qualities.” In addition, they're “subject to real estate cycles based on supply and demand, with the added stability of commercial leases. And they tend to be more sensitive to credit conditions due to the capital‐intensive nature of real estate.”

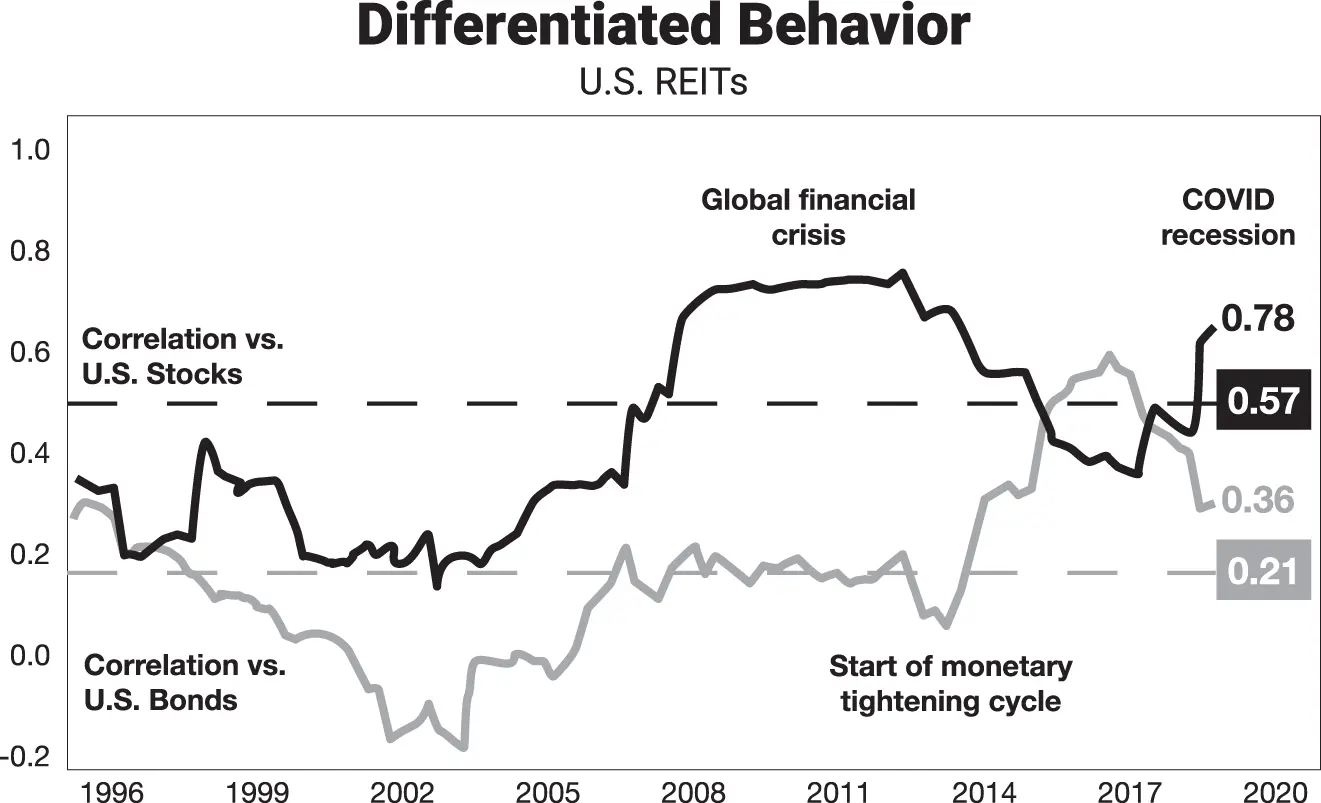

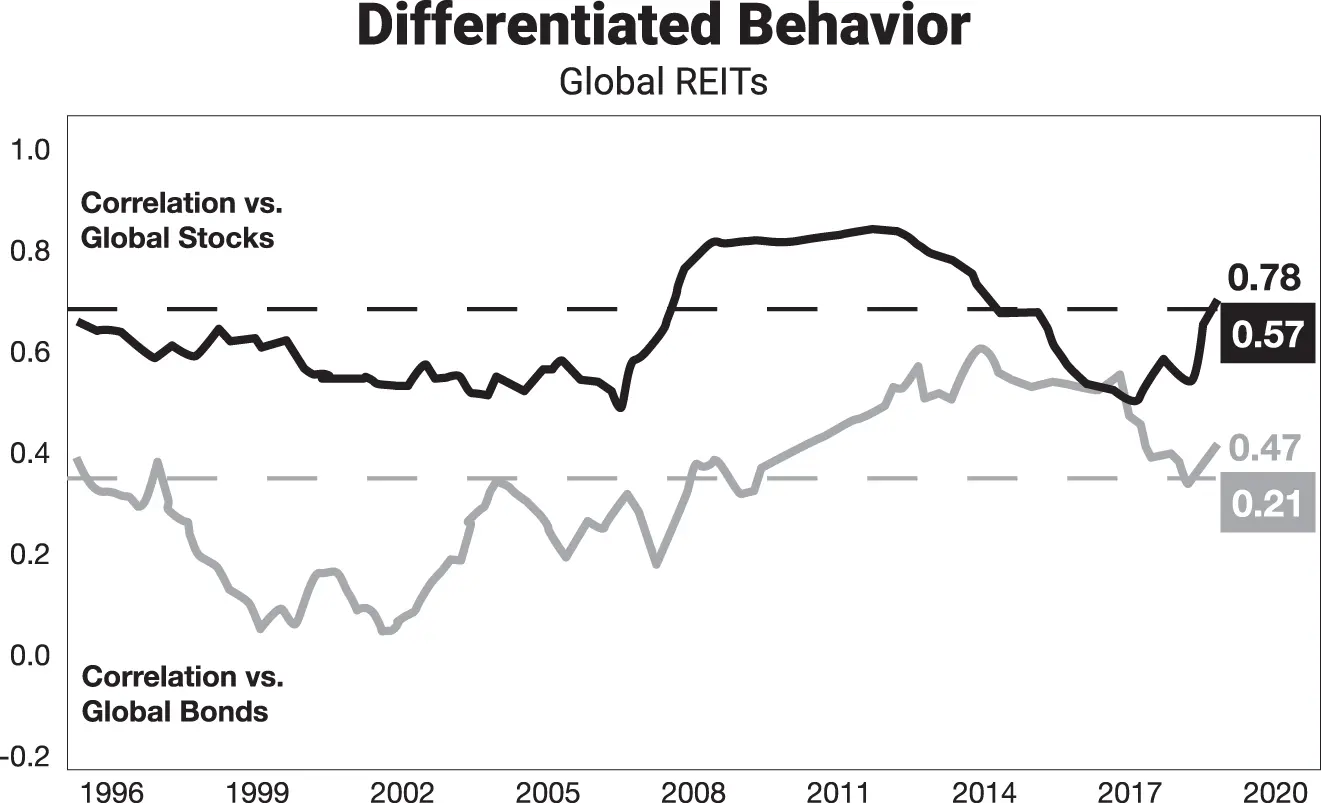

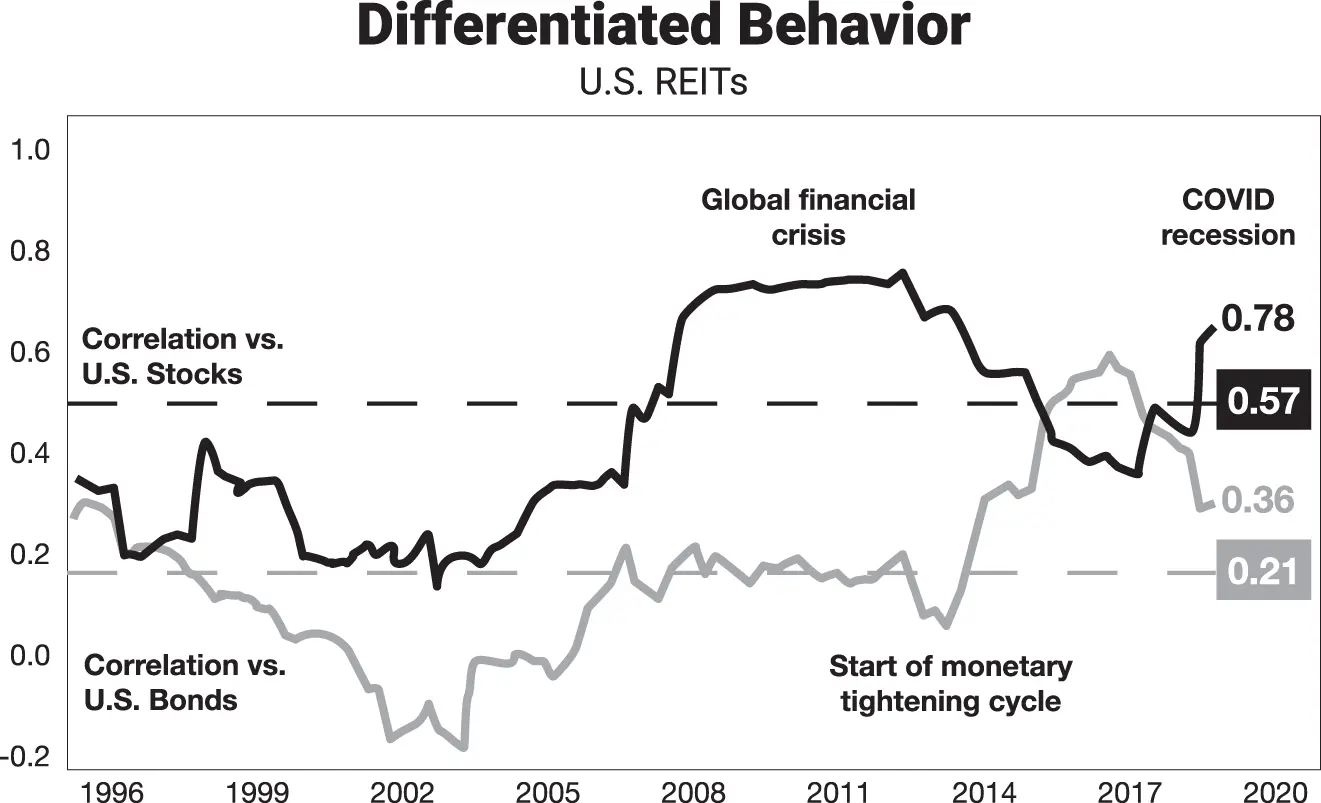

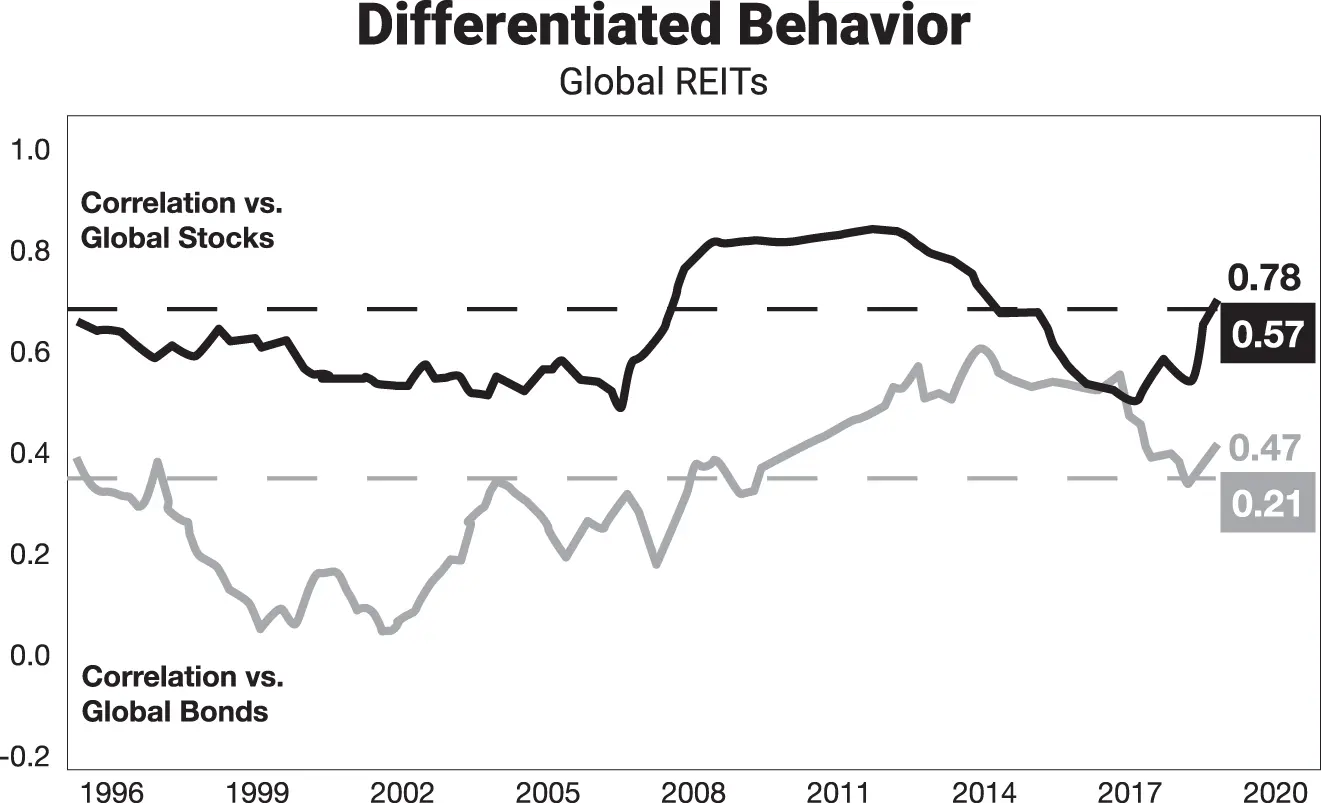

The co‐authors add that “these distinct performance drivers” have actually resulted in “low long‐term correlations with stocks and bonds. Since 1991, U.S. REITs have had a 0.57 correlation with the S&P 500 and a 0.21 correlation with U.S. bonds (see Figure 1.2). Global REITs have also exhibited diversifying correlations, albeit to a more modest degree, due largely to higher correlations of Asia's real estate market with both [Asian] and U.S. equities.” (See Figure 1.3.)

Accordingly, in markets where stocks are rising sharply, REITs may lag relative to the broad stock market indexes. This happened in 1995, when REIT stocks underperformed comparatively speaking while still providing investors with 15.3% total returns. And it happened again in 1998 and 1999, when their returns were actually negative. Conversely, during many equity bear markets – such as 2000–2001 – lower correlating stocks such as REITs tend to be more stable and may suffer less.

Figure 1.2

Source: Cohen & Steers.

Figure 1.3

Source: Cohen & Steers.

Durkay and Yablon add that “sudden changes in bond yields can have a meaningful influence on short‐term REIT performance. However, such periods tend to be temporary. In the long run, REIT returns are driven primarily by the distinct cash flows and growth profiles of the underlying property markets and the added stability of leases [that provide] the potential diversification benefits of an allocation to real estate.”

Bottom line: Correlations will vary over time, particularly during short time frames. However, because commercial real estate is a distinct asset class with distinct attributes, it's reasonable to expect REITs to maintain fairly low relativity to other asset classes over reasonably long time periods.

A stock's volatility refers to how much its price tends to bounce around from day to day or even hour to hour. Over the past four decades or so, REITs have proved to be less volatile than other equities on a daily basis. This has even been despite their increasing size and popularity, which has brought in new investors with different agendas and shorter time horizons.

Another factor that usually helps tamp down on such issues is REITs’ higher dividend yields. When a stock yields next to nothing, its entire value is comprised of all future earnings, discounted to the present date. If the perceived prospects for those earnings decline even just slightly, the stock can plummet. However, much of a REIT's value is in its current dividend yield. So a modest decline in future growth expectations will have a more muted effect on its trading price.

It's true that their volatility spiked from 2007 through 2009 due to concerns about their balance sheets and the American economy. And in 2020, the Covid‐19 pandemic also caused significant REIT volatility, though shares still didn't fall as hard as they did in 2008. This is because most of them were already reducing leverage and building up access to capital to strengthen their liquidity, which helped them immensely.

On the larger issue of volatility, Cohen & Steers adds, “At its Core, real estate exists to support basic needs of individuals and businesses, providing shelter and facilitating commerce.” And there will always be demand in that regard. It's only a matter of whether those needs are “housed in a different form or location,” or reflect “current preferences, such as residents moving from multifamily apartments in dense cities to suburban single‐family homes.”

Investment trends can change quickly and unexpectedly. In some years, REIT stocks will be very popular; in others, they'll be all but ignored. Admittedly, some “trends may be more permanent: accelerated e‐commerce adoption driving demand for industrial/logistics at the expense of retail.” Some examples include “greater reliance on digital infrastructure benefiting data centers and cell towers” and “increasing acceptance of work from home affecting office utilization.”

The rise of hedge funds – including those with very short time horizons – has added another wild card to the deck. REITs can sometimes become the sandbox in which these funds like to play, bringing more volatility with them than there otherwise would, or should, be.

The reason I bring this up is because it's important to know what can cause volatility in the stocks we purchase, REITs or otherwise. When our stocks go up, it's too easy to ignore risk in our pursuit of ever‐greater profits. And when our stocks drop, we too often tend to panic, dumping otherwise sound investments because we're afraid of ever greater losses.

Consider missed market expectations, which can play havoc on otherwise stable stocks. Let's say you own shares in a “regular” company that reports a 15% year‐over‐year increase in earnings. Yet because analysts expected a 20% increase, the stock drops. That scenario has played out more than once.

Fortunately, REITs are superior to most common stocks in this regard. Analysts who follow these companies are normally able to accurately forecast quarterly results, within one or two cents, quarter after quarter. This is because of the sheer predictability of the operations at work, especially when it comes to any property type that uses long‐term leases (which is most of them). That provides earnings stability that can't be found very easily elsewhere, further reducing both risk and volatility.

As a result, relatively few REITs have gotten themselves into serious financial difficulties over the years. Those that did were generally poorly managed and/or burdened by risky balance sheets.

Make no mistake: There are times to buy and sell. But prudent investors control their emotions, oftentimes by filling their portfolios with low‐risk positions like REITs.

As we already established, there's no way to avoid risk completely. Even simple preservation of capital carries its own risk, with inflation taking its typical toll on almost everything. So it should come as no surprise that real estate ownership and management comes with potential problems too.

The previously referenced Cohen & Steers report already broached the subject. It's easy to see that retail REITs are subject to the changing spending habits of consumers and that rising online capabilities are affecting offices. But every other property type comes with its own set of potential pitfalls. For instance, apartment REITs have to deal with varying popularity of single‐family dwellings and/or declining job growth. And the healthcare subsector constantly battles government decisions concerning healthcare reimbursement.

Читать дальше