The UK has often changed its NVQ system. The last substantial reform occurred in 2017 (Powell, 2019); the NVQ system is replaced by an apprenticeship system that offers level 2–7 programs that are equivalent to the education level . These programs are available in 1,500 occupations across more than 170 industries (Powell, 2019). Apart from that apprenticeship system, England has an education system offering Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC) programs, which are type FE2 of the classification in Table 2. Hence, it appears that the UK has two parallel systems, which is the case in the US, and has given up the accreditation of prior learning in the NVQ system. Because the NVQ degree does not exist, Backes-Gellner’s (1996) example can no longer be used in 2019. Now, it looks as if the new apprenticeship system in the UK could be a functional equivalent to the US registered apprenticeship (Lerman, 2010; Powell, 2019). However, an in-depth analysis would be required to confirm such an assumption.

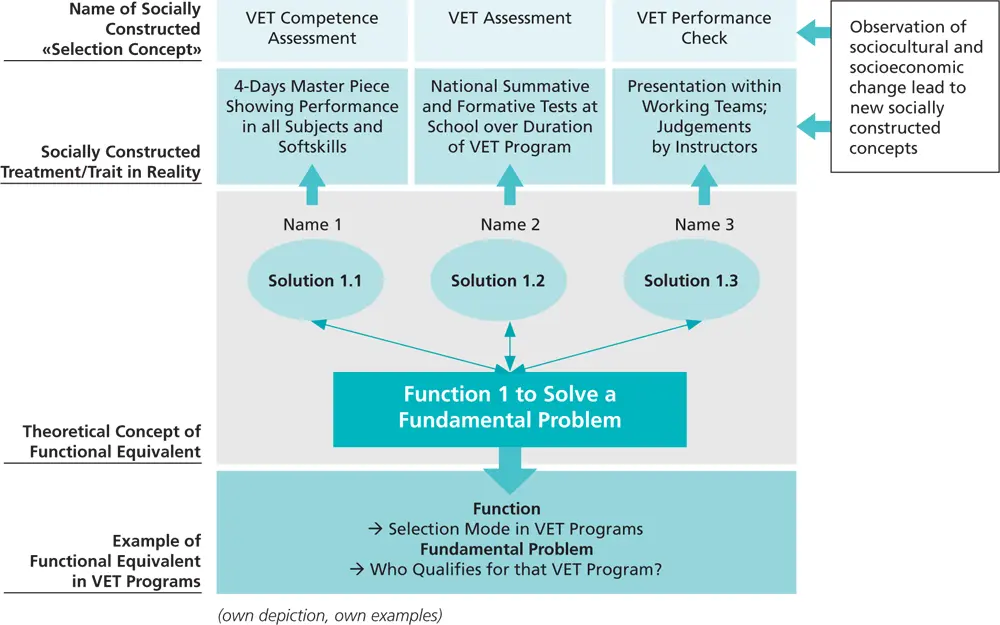

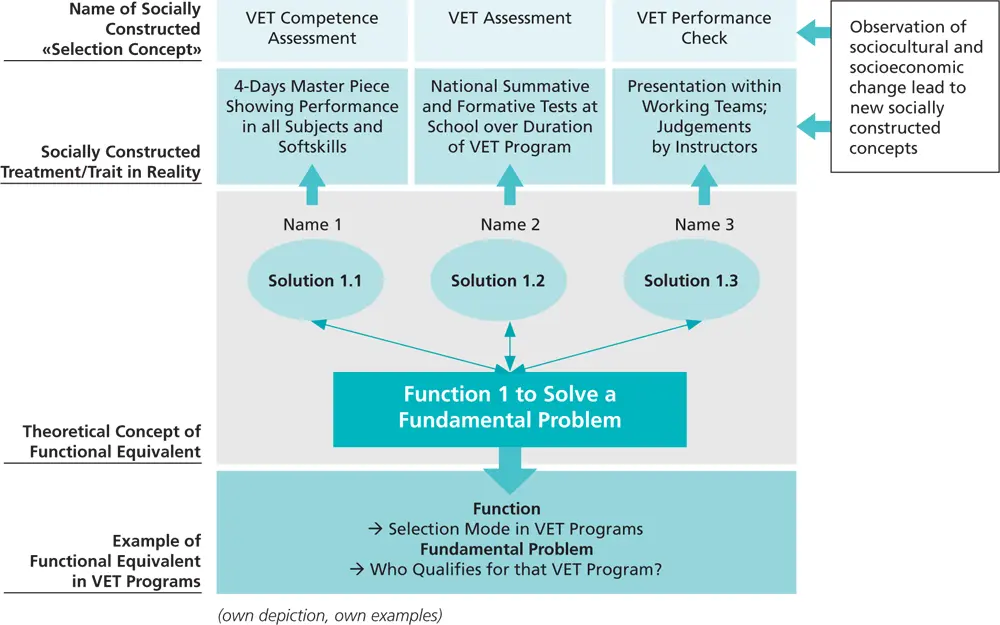

Figure 3: Socially Constructed Conceptual Equivalent and the Influence of Change in Society

To capture changes over time, socially constructed equivalent concepts must first be analyzed with cross-sectional analysis. On the right side, Figure 3shows where the influence of society comes from. We have seen that socially constructed concepts are constantly exposed to sociocultural and socioeconomic changes. The previous case of the UK developing its NVQ system into an apprenticeship system is just one example. Taking again the selection as a function developed in Figure 2and imagining that many countries change their curriculum development approach to be in line with competence-based standards in which soft skills are becoming highly relevant, we can derive another example that is reflected in the selection function and illustrated in Figure 3. While the socially constructed concept No. 2 is still the same as in Figure 2because nothing has changed in that jurisdiction, No. 1 and 3 have changed treatments and names over time. If two cross-sectional comparisons are carried out for the two static moments as represented in Figures 2and 3, then it must be determined how the variation is explained over time. What were the major social changes that happened in between?

In summary, a function can serve different traits or treatments across time. As was discussed in the statements in the section on definitions, a clear demarcation criterion is a conditio sine qua non to compare functions in VET programs. However, to identify the number of necessary functions that are sufficient for the functionality of an entire program, some theoretical and conceptual preliminary work must be performed. The field-specific theoretical framework for the VET program developed by Renold et al. (2019)may serve as a model. Only the robustness of all single social institutions as well as the configuration of various functional equivalents can ultimately make statements about VET program performance. Comparing whole VET systems presupposes that the architecture of functional equivalences and their interdependencies can be decoded; empirical research is still a long way from being able to demonstrate this. That said, it may become clear why it is so difficult to help other countries improve their VET system.

The article summarizes challenges and opportunities faced by leaders who want to initiate effective reforms in VET and by scientists who want to analyze VET. In general, most people agree that VET should prepare for future employment. If outcome effects are not as good as expected, reform leaders need to act. However, leaders must be aware that VET programs are socially constructed and depend on the political economy and other value-driven institutions. Additionally, trying to opt for a certain type of VET approach (such as that of Germany or Switzerland) means identifying functional equivalences between programs of interest. Furthermore, in most cases, an entire architecture of functional and conceptual equivalents must be identified to develop a strategy of how to reform the involved institutions. Functions are goal settings to overcome fundamental problems (Turner, 1997). If functions are fulfilled through socially constructed equivalent concepts, this can be seen as a robust social institution. Identifying and measuring the interplay of involved social institutions and their robustness may help certain reform processes succeed ( Renold et al., 2019).

The starting point of VET reforms is often bad outcome results on the labor market. However, it is not enough to criticize the actors of the education system because their graduates do not meet the requirements of the labor market. Policy-makers and reform leaders need to self-critically ask why the companies of an industry are not substantially involved in the training of future professionals and what kind of political economy underlines their behavior. Such sociocultural and socioeconomic analysis may explain challenges in the education and training approach and can act as an eye-opener for further policy measures.

Furthermore, every reform team needs to understand how to locate its current VET programs in its own education system. The classifications in this article can be an initial support. The next step is to decide which type of program a reform team wants to pursue. It is then indispensable to establish a relationship between the relevant actors and institutions and to involve them accordingly over a long time to develop robust social institutions ( Renold et al., 2019). If a country succeeds in institutionalizing the dialog among all the actors involved and better aligning education and employment systems throughout the entire education process, an important step will have been taken towards an effective VET system.

Autor, D. H., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118 (4), 1279–1333. doi:10.1162/003355303322552801

Bachleitner, R. (2014). Methodik und Methodologie interkultureller Umfrageforschung: zur Mehrdimensionalitaet der funktionalen Aequivalenz. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-04199-1

Backes-Gellner, U. (1996). Betriebliche Bildungs- und Wettbewerbsstrategien im deutsch-britischen Vergleich . Muenchen and Mering: Hampp.

Bereday, G. Z. F. (1964). Sir Michael Sadler’s study of foreign systems of education. Comparative Education Review, 7 (3), 307–314. doi:10.1086/445012

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality . New York: Anchor Books. doi:10.2307/323448

Black, B. (2007). Comparative industrial relations theory: the role of national culture. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16 (7), 1137–1158. doi:10.1080/09585190500143980

Blanpain, R., & Aaron, B. (Eds.). (1987). Comparative labor law and industrial relations (Vol. 3). Deventer, The Netherlands; Boston: Kluwer Law and Taxation Publishers.

Bolli T., & Renold, U. (2017). Comparative advantages of school and workplace environment in skill acquisition: Empirical evidence from a survey among professional tertiary education and training students in Switzerland. Evidence-based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 5 (1), 6–29. doi:10.1108/EBHRM-05-2015-0020

Brandl-Bredenbeck, H. P. (1999). Sport und jugendliches Koerperkapital: Eine kulturvergleichende Untersuchung am Beispiel Deutschlands und der USA, Sportentwicklungen in Deutschland (Vol. 8). Aachen: Meyer & Meyer.

Читать дальше