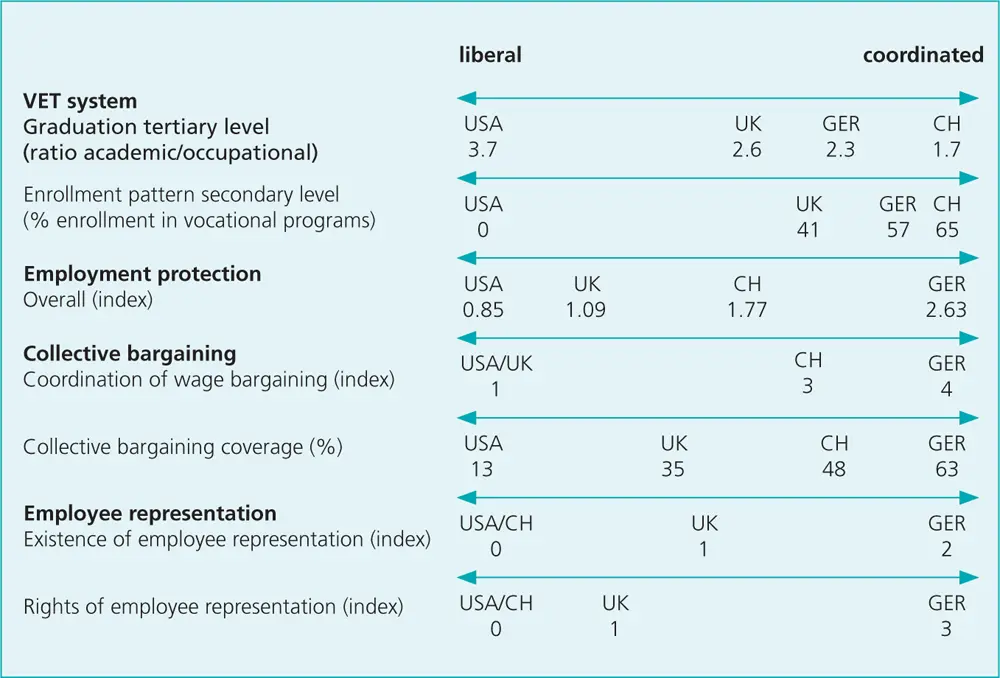

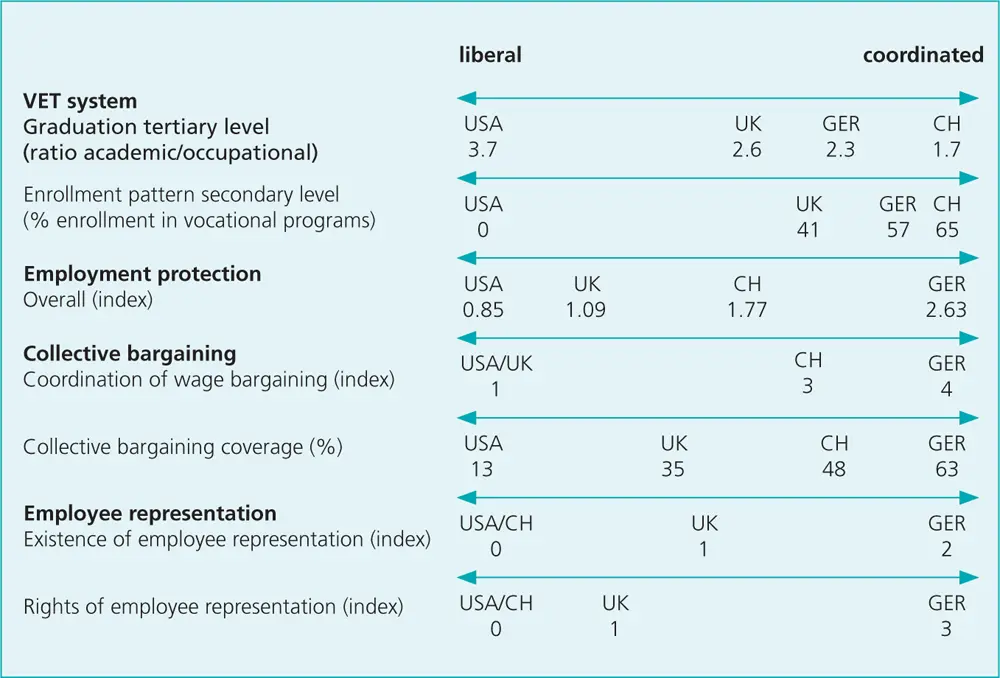

1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...16 Teuber, Backes-Gellner, and Ryan (2016)contributed with an investigation that shows the large differences in the configuration of institutions among the USA, the UK, Germany, and Switzerland. The authors analyzed how companies adjust their span of control (i.e., number of employees per supervisor) to national institutional settings. The authors show that a broad control span goes hand in hand with certain national institutional conditions, namely, a solid skills foundation, skill retention, and trust. Highly qualified and trained employees need fewer supervisors to support and monitor them. Because these employees have broader education and training and more work experience, which they have gained in their VET program, they can take on more demanding jobs. This possibility leads to more motivation, which particularly has an influence on skills retention and trust. The institutional framework conditions used in the authors’ approach are summarized in the following table and show how 22 companies from the USA, the UK, Germany, and Switzerland can be classified. This table makes it clear that the Anglo-Saxon countries, the USA and the UK, belong to the LMEs, Germany to the CMEs, and Switzerland is somehow a hybrid of both concepts.

Table 1: Overview of National Level Institutions (for details see Teuber, Backes-Gellner, & Ryan, 2016)

Today, we live in a different world with many disruptive processes driven by digital transformation, the acceleration of all areas of life, and globalization. Workforce qualification requirements have changed and will change faster in the future. Reform leaders have begun to realize that their education system is not preparing people for the 21 stcentury. The worldwide demand for more experience and soft skills in job advertisements (Salvisberg, 2010; Trilling & Fadel, 2009; Bolli & Renold, 2017) indicates that there is a need for radical change in education, which goes beyond simple market-driven and “laissez faire” concepts, especially if a society wants to provide long-lasting career paths for its younger and older generations. As Winch (1998) summarized, due to ramifications throughout society and politics, reform leaders must develop goals and stimulate discussions about values, beliefs, and habits to inspire a common pattern of behavior to achieve robust social institutions ( Renold et al., 2019).

This short summary of economic policy concepts shows that the predominant capitalist institutional structure has a decisive influence on VET approaches and education in general and therefore contributes to the social construct of the concepts in VET. However, that short summary is not sufficient to differentiate between social constructs of VET program concepts. To provide a way forward in understanding comparison issues in VET, the following section addresses definition issues, provides a classification scheme with selected criteria, and discusses forms of construction metaphors.

2.4 Methodological Problems of Definitions

2.4.1 Problems of Definitions

VET programs are complex because — in contrast to general education programs — they have to link two social systems, i.e., the education system and the employment system ( Rageth & Renold, 2019; Renold et al., 2017; Renold et al., 2015; Eichmann, 1989). Both social systems may have institutional configurations that vary greatly, depending on influencing historical events (i.e., colonialist footprint), socioeconomic conditions, and political schools (i.e., LME, CME) influencing the character of an employment system. It is therefore comprehensible that attempts are being made to find a generally valid definition for VET around which reform leaders can orient themselves.

Some definitions illustrate why this issue is a problem: Vocational education and training refer to the sector of the education system which is aimed at imparting qualifications and normative orientations for occupations in defined functional and positional areas of the employment system. The customary use of the term today excludes academic training courses (Krumme, 2018, para. 1).

The CEDEFOP (2014) notes that “education and training which aims to equip people with knowledge, know-how, skills and/or competences required in particular occupations or more broadly on the labour market” (p. 292). UNEVOC states that “Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is concerned with the acquisition of knowledge and skills for the world of work” (UNEVOC, 2019). The Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC) presented its definition as follows:

Vocational Skills Development (VSD) encompasses all organized learning processes for the development of technical, social and personal competencies and qualifications that contribute to the sustainable long-term integration of trained people in decent working conditions into the formal or informal economy either on employed or self-employed basis. (SDC, 2016, p. 6[7])

While, in the first definition, the embeddedness of the VET level in the education system is expressed, this is not explicitly the case in the other definitions. Furthermore, it is not clear whether the definitions refer to formal or nonformal education (Carron & Carr-Hill, 1991; Eshach, 2007; DGIZ, 2016).

Such definitions do not help to identify transnational categories (Brockmann et al., 2009), as they are too general. Braun (2006) points out what problem might arise by using such definitions: “So the construct is defined differently broadly in different countries. If important aspects are missing in the comparison for a construct in some countries, the term ‘construct underrepresentation’ is used (Van de Vijver, 2003)” (p. 18). Braun emphasized, by relying on Sartori (1970, 1991), that transferring the social constructs of concepts to another country may lead to conceptual stretching , i.e., a lack of adaptation of the conceptual content to the possibly different context conditions. “To make a concept more generally usable, i.e., to increase the extension, its properties must be reduced, i.e., to reduce the intensity” (Braun, 2006, p. 18[8]). In most policy-driven attempts to precisely define VET, the opposite occurs. Therefore, I conclude that it is difficult to define VET programs or VET systems as a transnational category. These systems are too different with regard to the social constructs of concepts and are most likely founded on different political economy concepts. One has to reduce the complexity of VET to a specific transnational concept so that comparisons have a valid foundation (see example Rageth and Renold, 2019).

Popper and Hansen (2012, 1979) discussed the problem of definition in detail. In their theory of method,[9] Popper and Hansen wrote about the empirical character of everyday language, which is a topic that is of great importance for the study at hand. To speak of “empirical science” would require clear demarcation criteria. As soon as there is a controversial boundary criterion, it is not clearly defined what applies since the different boundary criteria can represent different positions in the controversy. If in science one definition is preferable to another, this is related to its “(theoretical) productiveness” (Popper & Hansen, 2012, p. 401). With the term theoretical productiveness , Popper and Hansen referred to Menger’s (1928) “Dimenionstheorie,” stating that every “definition (…) contains a certain degree of arbitrariness, whose justification can be furnished only by the productiveness of the definition” (p. 76). Popper and Hansen concluded from this assumption that the purpose of a definition is the starting point for a deductive system, where definitions are dogmas and only conclusions produce insights (Popper & Hansen, 2012, 1979). Guaranteeing the empirical character of the concepts and thus having an “empirical” characteristic in common is a minimal requirement for a definition.

Читать дальше