1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...16 The theory of definitional rules would, however, be analogous to logic (the theory of inferential rules) and equivalent to ‘methodology’ (the theory of statement usage); but equivalent at best, and that only if it really manages to accomplish what methodology accomplishes. (Popper & Hansen, 2012, pp. 404–405)

The application of a concept is not determined by definitions but by the use of the concept, which is called its “meaning”. In other words, there are only “working definitions” (Popper & Hansen, 2012, p. 405; German: “Gebrauchsdefinition”; Popper & Hansen, 1979, p. 367). I conclude that the social construct of VET cannot be defined per se. Characteristics must be identified that clearly determine the empirical character and lead the scholar and reader to demarcation criteria that are comparable. The next section is devoted to this topic.

2.4.2 Classification Scheme for VET Programs

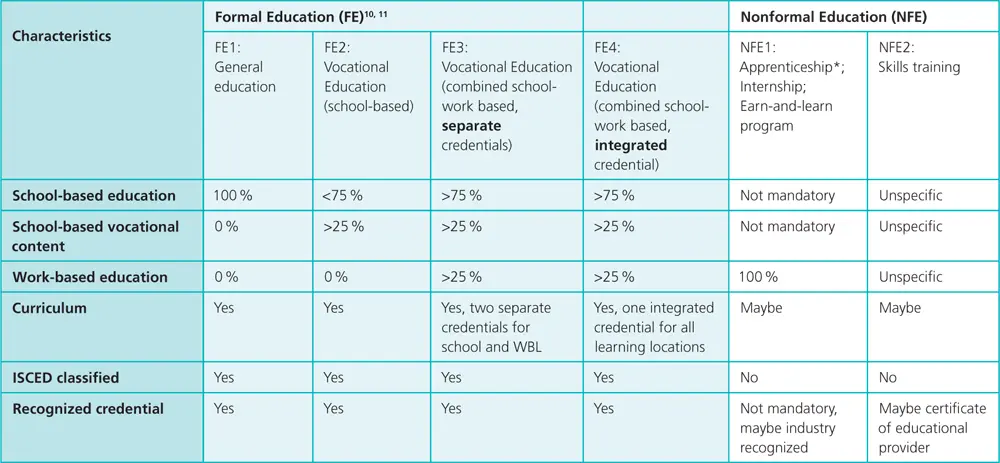

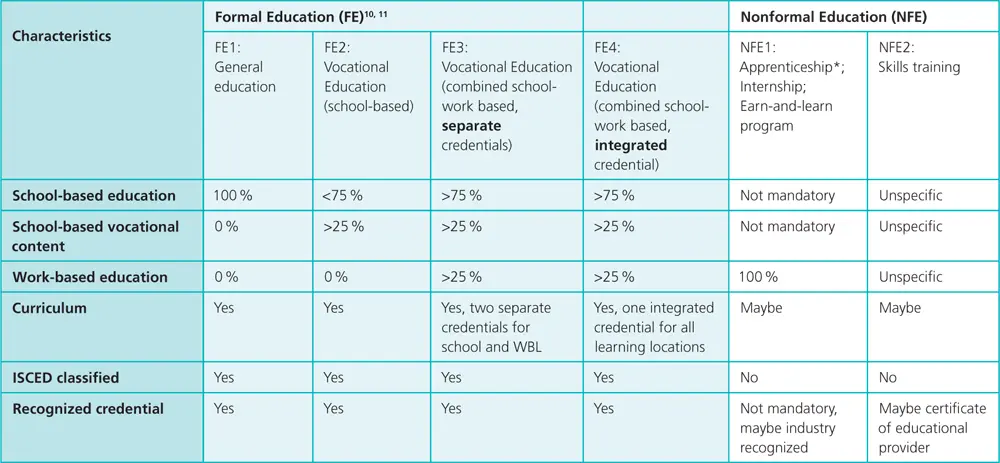

Table 2provides a nonexhaustive classification of VET program types using several characteristics as demarcation criteria. However, there are still limitations with regard to construct underrepresentation or conceptual stretching (Braun, 2006), as several other criteria and dimensions are not included, i.e., how representative the program is or what social institutions are involved.

By providing a first classification, I distinguish between formal and nonformal education programs. Formal, nonformal, and informal education are different forms of education. Although definitions of the three forms are fuzzy and context dependent, they help to distinguish between important features such as different institutional conditions (Carron & Carr-Hill, 1991; Eshach, 2007; DGIZ, 2016). That said, I understand formal education to be part of the formal education system, which is structured and guided by an enacted qualification standard or curriculum. Program credentials are recognized by the country’s education authority. The VET program type FE1-FE4 belongs to formal education. Nonformal education is structured courses that are not recognized by the education authority. Quality criteria vary greatly among such courses. However, nonformal education (often named as continuing education) is becoming an important form of education due to the rapid change in qualification requirements in the labor market and the need for retraining adults. Type NFE1 and 2 belong to nonformal education. Informal education occurs in everyday life. It is not intentional, structured, or recognized by any authority, and thus not included in the classification.

Table 2: Classification of Formal and Nonformal Education Programs

Legend: FE= Formal Education; NFE = Nonformal Education, WBL = Work-based Learning; ISCED = International Standard Classification of Education; *Apprenticeships without recognition of the national education authorities are nonformal programs. They are not allocated to the international standard classification of education ISCED (UNESCO, 2011). Typical example is the registered apprenticeship in the US, led by the Department of Labor (Lerman, 2010, 2012).

As these characteristics show, there are large differences in the organization of the social process to construct a particular type of VET program. On the one hand, VET programs can be offered in whole or in part by VET schools (FE1, FE2). In addition, Vocational School students spend more or less time learning and working in companies. This problem has already been recognized in the OECD study “Learning for Jobs” (OECD, 2010) and led the OECD to define some criteria for classifying education programs as part of the VET subsystem. For example, the USA does not appear at all in these statistics because the proportion of vocational content does not meet these criteria, even though some states have so-called vocational high schools (OECD, 2017). Some articles in this handbook address the concept of apprenticeship . This term may mean that the program is an operational part of the dual VET program (e.g., FE3 or FE4) that is recognized by the education system authority (as in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland), but it may also be a pure labor-market integration program (e.g., NFE1), leading people into a job as quickly as possible (UNESCO, 2011). The latter are not part of the education system as they are not recognized as formal qualifications by the education authorities (Ryan, 2000). Examples of such programs are the “registered apprenticeship” run by the US Department of Labor (Lerman, 2010) or the apprenticeship in the UK (Steedmann, 2001; Fuller & Unwin, 2003; Powell, 2019). This simple classification scheme does not provide information about the social constructs of those characteristics. To overcome the problem of comparing socially constructed concepts in VET across countries, further methodological considerations are required.

2.4.3 Forms of Construct Metaphors

In his essay, Sismondo (1993) described various types of social constructs and analyzed the following four forms of construction metaphors:

a)the construction, through the interplay of actors, of institutions, including knowledge, methodologies, fields, habits, and regulative ideals;

b)the construction by scientists of theories and accounts, in the sense that these are structures that rest upon bases of data and observations;

c)the construction, through material intervention, of artefacts in the laboratory, and

d)the construction, in the neo-Kantian sense, of the objects of thought and representation. (p. 516)

For the current article, I limit myself to the first two forms (i.e., type a and b), which are mostly relevant for understanding the socially constructed concepts used in the literature on VET. Type a) is required to theoretically decontextualize the configuration of institutions and actors and identify functions of VET programs. Type b) applies to social constructs that are used in empirical research.

Analyzing VET across countries and taking the meaning of type a) seriously requires decontextualizing the configuration of institutions and actors and identifying the functions behind VET programs. The first metaphor addresses many different things and must be broken up into elements so that presuppositions are easier to identify. Relying on Berger and Luckman’s (1967) construction of institutions, Sismondo (1993) stated the following:

And insofar as all human ‘knowledge’ is developed, transmitted and maintained in social situations, the sociology of knowledge must seek to understand the processes by which this is done in such a way that a taken-for-granted ‘reality’ congeals for the man in the street. In other words, we contend that the sociology of knowledge is concerned with the analysis of the social construction of reality. (p. 517)

Hence, we are confronted with institutionalism theory, which explains how social institutions emerge and develop over time and space. Institutionalism theory developments (e.g., Parsons, 1940; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1991; Scott & Meyer, 1994; Scott 2008; Rogers, 2017) lead to several insights about processes and principals that control the common pattern of the behavior of actors to solve fundamental problems (Turner, 1997) and hence construct reality . Fligstein (2001) highlighted the importance of socially skilled actors for such processes, e.g., actors that empathetically interact with others to strengthen the common pattern of behavior and, in the end, the social institution (Miller, 2019). Fligstein (2001) saw these actors as a relevant force in the construction process of social reality.

Читать дальше