1 1It is interesting to note that some recent and very prominent handbooks on Iranian history even appear reluctant to deal with the problem at all and do not include a chapter on the Medes: Daryaee (2012) and Potts (2013).

2 2Additionally, one has to stress that the perception of space is not an absolute value – 2300 km was a much larger distance in Cyrus' times, when Lydia was perceived to be at the western fringes of the world.

3 3The adoption of the term “Mede” as a general synonym for “Persian” in Greek sources, attested since the later sixth century BCE, can be seen as evidence of an ephemeral contact between Medes and Greeks in Asia Minor that originated in Median raids to central Anatolia.

4 4The alleged intermediary role in transmitting Neo‐Assyrian artistic traditions with political connotations subscribed to the Medes by modern scholars can be ascribed to Elam or to the Neo‐Babylonian Empire (Seidl 1994; Liverani 2003; Waters 2005: p. 527).

CHAPTER 26 Urar  u

u

Mirjo Salvini

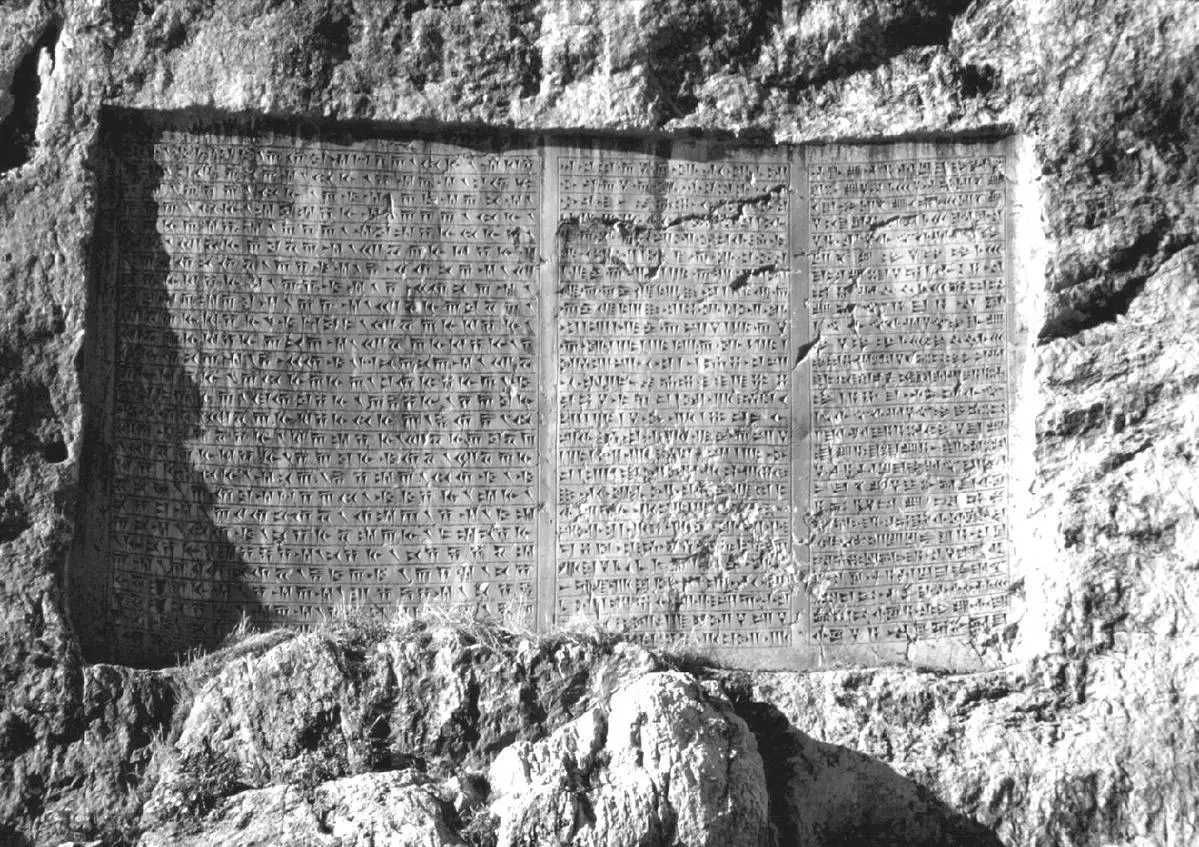

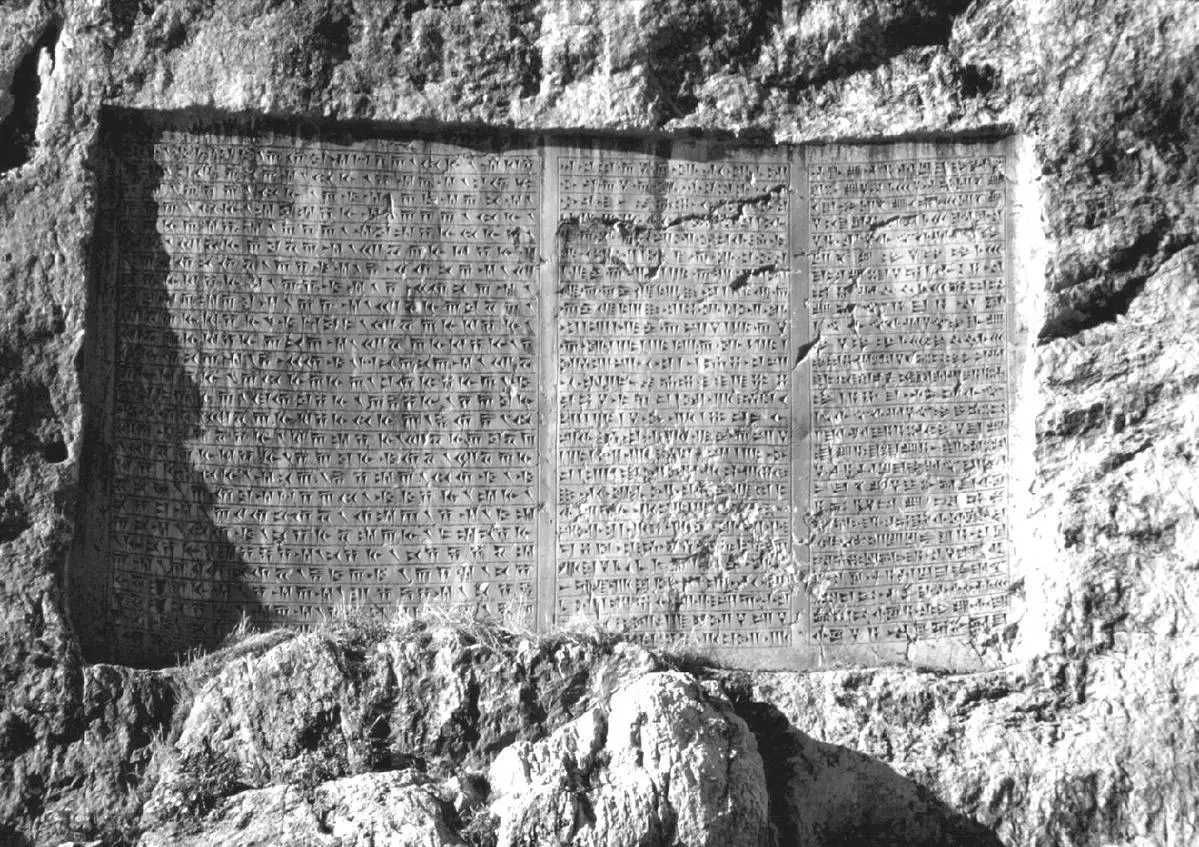

On the southern slope of the Rock of Van, on the eastern shore of Lake Van in eastern Turkey, still today one can admire this trilingual inscription by Xerxes, son of Darius ( Figure 26.1):

Figure 26.1 Van, trilingual rock inscription of Xerxes I.

“A great god is Ahuramazda, the greatest of gods (…) (16–27) Saith Xerxes the king: King Darius, who was my father, he by the favour of Ahuramazda built much good (construction), and this niche he gave orders to dig out, where he did not cause an inscription (to be) engraved. Afterwards I gave orders to engrave this inscription. May Ahuramazda together with the gods protect me, and my kingdom, and what has been built by me”

(Schmitt 2009: pp. 180–182: XVa).

In spite of its generic content, there is a symbolic and programmatic significance in the very fact that this inscription was engraved in the central part of Van Kalesi ( Figure 26.2), the old Urartian capital Ṭušpa, beside the monumental rock chambers and inscriptions of the Urartian kings of the ninth and eighth centuries BCE. This is the only royal Achaemenid inscription outside of Persia. Its position proves that Darius and Xerxes were fascinated by the site and recognized the importance of the old kingdom of Urarṭu − henceforth part of the Achaemenid Empire as the satrapy of Armina (Old Persian § 6 I: Schmitt 2009: pp. 36–91)/Urašṭu (Accadian § 6.23.24: Malbran‐Labat 1994) – for the ideology of their kingship (Seidl 1994).

Figure 26.2 The Rock of Van in 2008.

Although 瞈ušpa at Xerxes' time had been abandoned for one and a half centuries, the monumental achievements of the Urartian kings were certainly visible between the end of the sixth and the beginning of the fifth centuries BCE.

It would be astonishing if the Persian kings, knowing the accomplishments of this civilization, which was older than the Median one, were not somewhat influenced by it.

Assyrian Records on Urar  u

u

In the Assyrian annals we first encounter the name of Urarṭu (in the forms Uraṭri/Uruaṭri), which was one of the principal objectives of the Assyrian expeditions toward the northern mountains from the Middle Assyrian period on, that is to say starting from the thirteenth century BCE (Salvini 1995: 18 ff). The populations that settled north of the Taurus range were repeatedly invaded by the Assyrian armies of Shalmaneser I (1273–1244), Tukulti‐Ninurta I (1243–1207), Tiglath‐pileser I (1114–1076), and Aššur‐bel‐kala (1073–1056). The name Urarṭu is attested in the Assyrian annals from the ninth century onward. But also Nairi (RlA s.v.) is important for the history of Urarṭu, because the first Urartian kings of the ninth century BCE, Sarduri I (RlA s.v.) and his son Išpuini (in the Assyrian version of his bilingual stela of Kelišin: CTU A 3‐11) claimed to be “king of the country of Nairi,” thus linking up with a prestigious political tradition of the independent mountain populations. The cuneiform inscriptions of Išpuini and the following kings designate them even as “King of the country of Biainili,” a local name which later corresponds to Urarṭu in the Assyrian version of the bilingual stelae by Rusa I (CTU A 10‐3, Movana, and 5, Topzawa).

One of the natural gates through the eastern Taurus lies on the modern road connecting Diyarbakır with Bingöl. In the eleventh century BCE Tiglath‐pileser I, and after him Shalmaneser III in the ninth century, left written records on the border of the Urartian territory: the famous reliefs and inscriptions on the “Tigristunnel” (RlA s.v.). The annals of Shalmaneser III record the conquest of Sugunia, the city of “Aramu, the Urartian,” in 858 BCE and his “royal city” of Arzaškun in 856 BCE. In 832 BCE the Assyrian field marshal crossed the river Arsania (Murad Su) and defeated “Seduru, the Urartian” (RlA s.v. Salmanassar III). This new name is the link with the indigenous Urartian documentation, namely with Sarduri I (RlA s.v.).

Tušpa, Center of the Urartian Power: Sarduri I

The oldest building in Van Kalesi is the “Sardursburg,” defined thus by Lehmann‐Haupt during his “Armenische Expedition” in 1898–1899 (Lehmann‐Haupt 1926: 18 ff). This structure of huge well‐squared limestone blocks laid in five regular courses was probably a quay or wharf. Six cuneiform inscriptions are carved into these blocks in the Assyrian language and Neo‐Assyrian ductus. They are all duplicates of the text of Sarduri I (c. 840–830 BCE), who must be considered as the founder of the Urartian capital 瞈ušpa (Salvini 1995: pp. 34–38):

Inscription of Sarduri, son of Lutipri, great king, powerful king, king of the universe, king of Nairi, king without equal, great shepherd, who does not fear the fight (…). Sarduri says: I have brought here these foundation stones from the city of Alniunu, I have built this wall

(Wilhelm 1986: p. 101).

With this written document, which was discovered by the pioneer Schulz together with other 41 Urartian inscriptions (Schulz 1840), begins not only the history of the Urartian kingdom but also the written documentation for the entire mountainous region stretching across eastern Turkey, Armenia, and Iranian Azerbaijan.

We have no other written records signed by Sarduri I documenting his deeds, but the very fact that he fought against the powerful Assyrian king Shalmaneser III demonstrates a certain political importance and military power.

Sarduri's son Išpuini (end of the ninth century BCE) introduced the use of the indigenous Urartian language, the language of the dynasty. He left us some building inscriptions celebrating the construction of a system of fortresses around Van (CTU A 2). Very soon he involved his son and heir apparent Minua in his military expeditions directed to far‐lying countries such as the region north of the river Araxes, the basin of Lake Urmia, and the province of Nakhičevan.

The two kings campaigned against the tribes of Luša, Katarza, and Uiteru  i in today’s Armenia (CTU A 3‐4–A 3‐7) and in the modern territory of Nakhičevan (CTU A 3‐8).

i in today’s Armenia (CTU A 3‐4–A 3‐7) and in the modern territory of Nakhičevan (CTU A 3‐8).

Читать дальше

u

u

i in today’s Armenia (CTU A 3‐4–A 3‐7) and in the modern territory of Nakhičevan (CTU A 3‐8).

i in today’s Armenia (CTU A 3‐4–A 3‐7) and in the modern territory of Nakhičevan (CTU A 3‐8).