In theory, shareholders appoint directors. In practice, however, shareholders simply ratify director candidates selected by the board's nominating committee, although the proxy voting process has become increasingly complex due to activist discontent. 34 As described in more detail in the Strategic Governance Highlight ( Box 1.3), activist board members are elected to targeted boards and often represent wolf pack hedge funds who have teamed together. These board members push for share price increases and other activist agenda items, which may come at the expense of other stakeholders. The nomination process is hence critical in making appropriate director appointments, as the effectiveness of the board with regard to its monitoring role depends on the quality of the board members selected. 35

BOX 1.3Strategic Governance Highlight: How Did Boards Become More Activist-Oriented?

The 1980s was known for hostile takeovers and the use of junk bonds to facilitate large takeovers by corporate raiders. This period inspired a book and movie titled Barbarians at the Gate , which chronicles the takeover by Kolberg, Kravis, and Roberts (KKR) of RJR Nabisco in a stunning $24 billion deal. However, in the early 1990s, the market for corporate control became dampened after the collapse of the junk bond market and the jailing of Michael Milken and the failure of his firm, Drexel Burnham Lambert.

In the late 1990s, institutional investors, such as pension funds and mutual funds, became more active. Although institutional investor activism rose in this period, the market for corporate control declined because of defensive actions by boards that largely insulated firms from pressure. But activist hedge funds stepped in with more offensive actions. In the 2000s, activist hedge funds began to nominate unaffiliated board members and influence their election to boards. One legal observer called this approach quasi-control because it uses board power rather than just ownership voice, as pension fund holders had used in the 1990s, although it falls short of actual corporate control. When activist fund representatives fill one or more board seats, their influence often leads to the replacement of significant corporate managers, such as the CEO or CFO, and the replacements often favor the strategic decisions preferred by the activists.

In wolf-pack activism, funds ready for aggressive campaigns team together with other activist investors. This tactic may include securing minority board representation (especially by way of negotiated settlement), which represents a much cheaper alternative to engaging in a proxy contest or pursuing a hostile takeover. In this manner, activist hedge funds can pursue a number of different companies compared to focusing their efforts entirely on one or two targets. As such, the amount of capital that they need to invest in specific target companies has gone down over time.

What regulatory and other changes occurred to allow for an atmosphere of wolf-pack activism? Changes in Securities and Exchange Commission regulations and the entrance of shareholder proxy advisory intermediaries facilitated the changes. The SEC enacted a proxy access rule in 2010, though it was later vacated by the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 2011. However, in recent years, many S&P 500 companies have adopted proxy access bylaws, which usually allow shareholders who hold 3 percent of the shares of a company for at least three years the ability to nominate directors without going through a proxy contest. Rather than risk a proxy contest, firms have allowed more access to the nomination process. In fact, 88 percent of the board seats won in 2016 were achieved through settlement agreements rather than proxy contests, compared to 70 percent in 2013 and 66 percent in 2014.

Proxy advisory intermediaries, such as Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis, have enabled the power of other institutional investors, often in support of the activist shareholders. Because institutional investors are significant shareholders, often having shares over the SEC 3 percent rule, they hold power to nominate directors directly during the proxy voting process. And because institutional investors frequently follow large proxy advisor voting recommendations, activist investors team with these intermediaries to get their board members elected. Under SEC rule changes and proxy advisor power, firm leaders are more likely to settle with activist shareholders and support a campaign for minority board representation rather than risk a negative vote in a proxy contest.

Sources: Benoit, D., & Grant, K. (2015). Activists' secret ally: Big mutual funds – large investors quietly back campaigns to force changes at US companies. Wall Street Journal, www.wsj.com, August 10 www.wsj.com/articles/activist-investors-secret-ally-big-mutual-funds-1439173910; Coffee J. C., & Palia, D. (2016). The wolf at the door: The impact of hedge fund activism on corporate governance. Journal of Corporation Law 41(3): 545–607; Baigorri, M., & Kumar, N. (2017). Black swans, wolves at the door: The rise of activist investors. Bloomberg , www.bloomberg.com, July 12; Christie, A. L. (2019). The new hedge fund activism: Activist directors and the market for corporate quasi-control. Journal of Corporate Law Studies 19(1): 1–41; Wong, Y.T.F. (2020). Wolves at the door: A closer look at hedge fund activism. Management Science 66(6): 2347–2371.

For board members to affect strategic governance, the same standard applies. Corporations often replace one or more directors each year. Each replacement represents a chance to shape the board to meet the corporation's strategic needs. An unexpected death of one director can shape corporate acquisitions strategy, which indirectly shows the impact on strategy that even one director can have. 36 Not surprisingly, nominating committees increasingly seek board members with specific functional expertise, such as in labor, environmental, compensation, or public policy. For example, when a firm is experiencing operational problems, appointing a chief operating officer (COO) or CEO with operational experience from another firm helps the appointing firm to improve its performance. 37

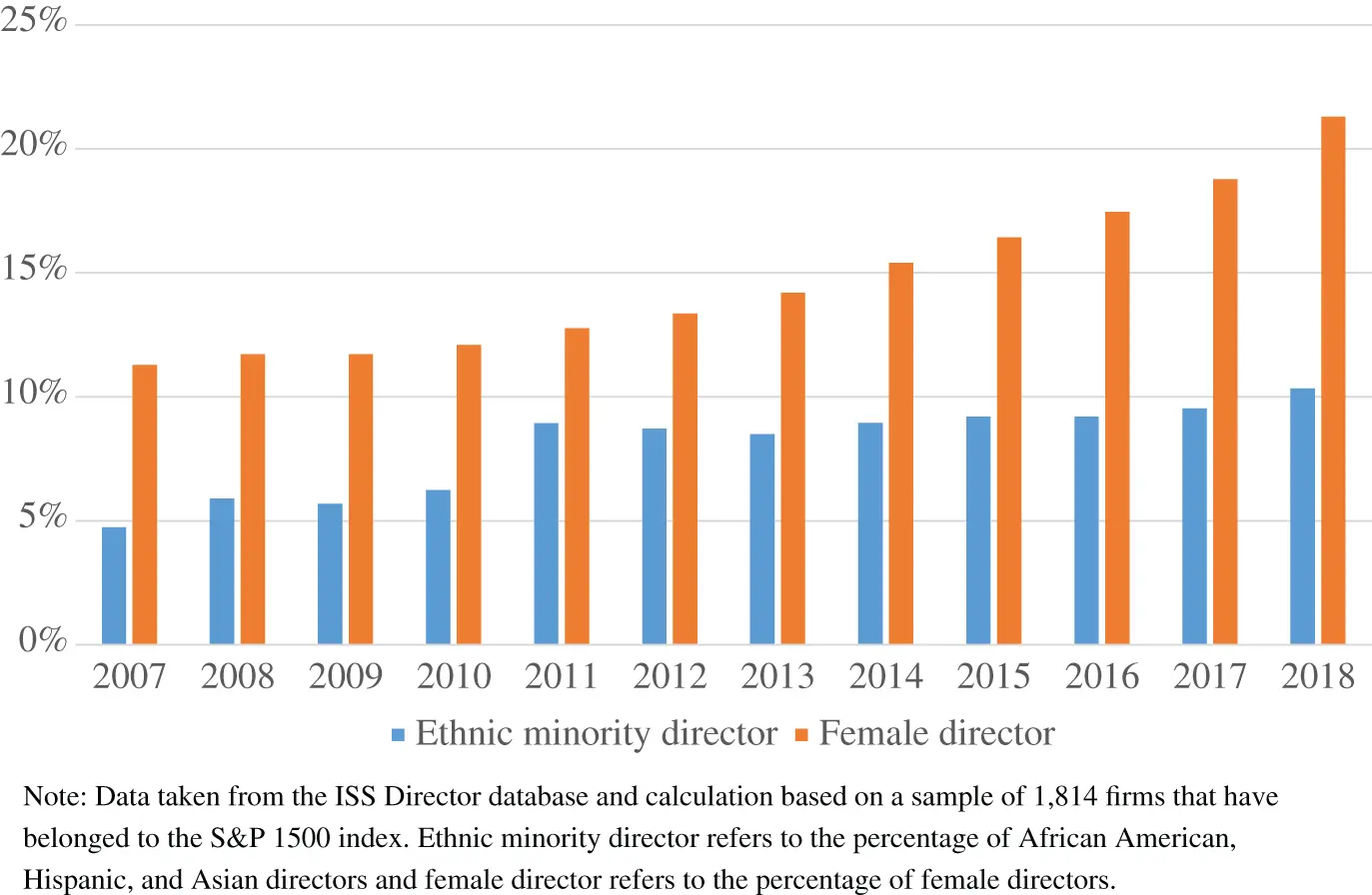

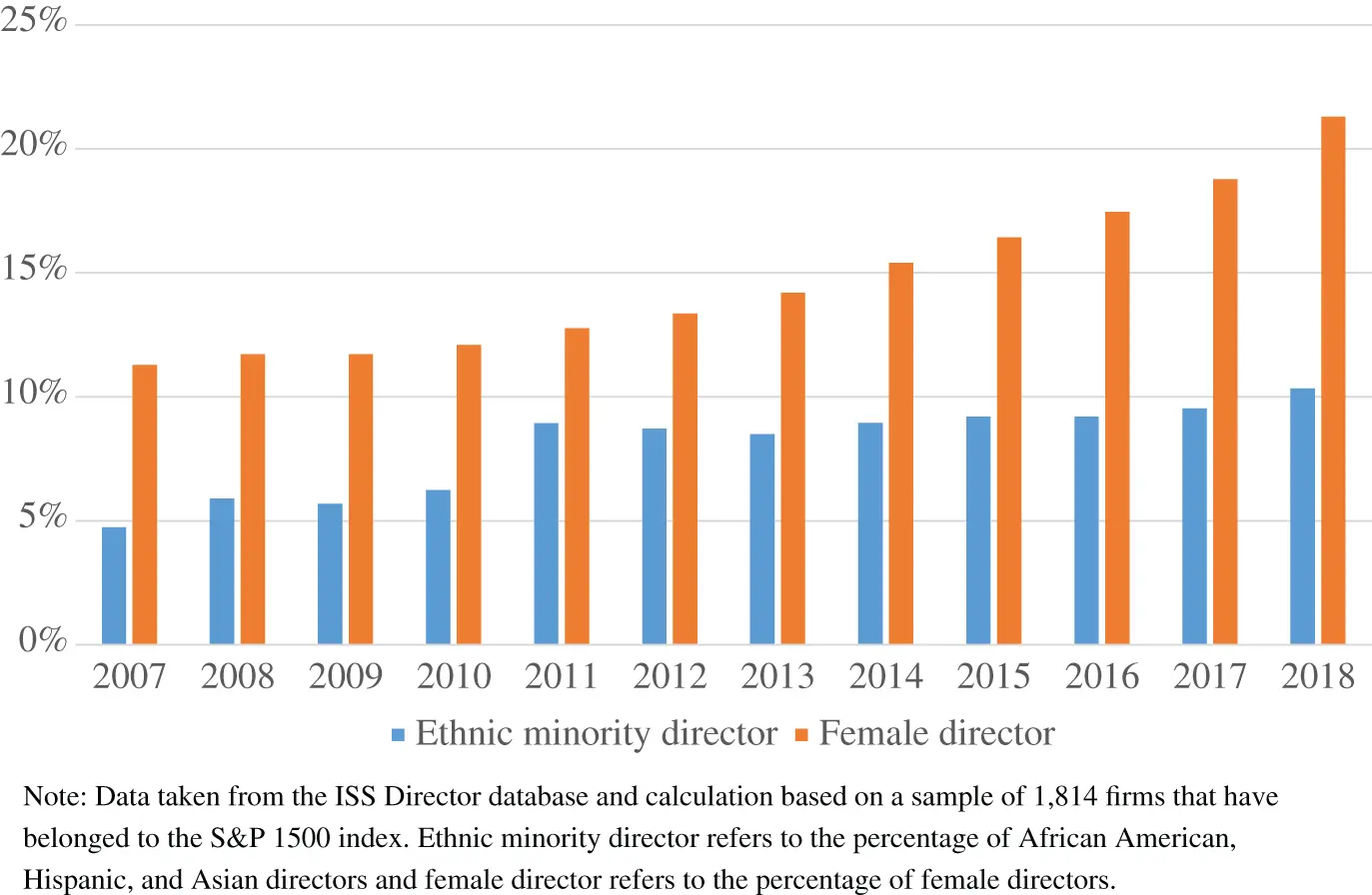

FIGURE 1.2 Board diversity of S&P 1500 firms.

Nomination committees may also seek directors to match diversity characteristics of customers or to extend operations into global markets. Diversity may improve board effectiveness. Growing evidence suggests that board gender diversity is associated with a number of desirable organizational outcomes, such as avoidance of securities fraud, 38 more vigilant monitoring of the top management teams, 39 more ethical firm behavior, 40 and higher accounting-based performance and stock market returns. 41 As Figure 1.2shows, boards have become more diverse over time in regard to appointing more females and ethnic minority members. But these positives are stymied if, for example, solely one woman is placed on a board as a token to create institutional legitimacy. 42 Recognizing the positive effects of diverse membership on boards, institutional investors are using their power to push companies to appoint more women and minorities. For instance, BlackRock, a large mutual fund manager, suggested that diverse boards “make better decisions” and that it planned to focus on the issue in discussions with company leaders ahead of annual meetings. 43 Yet we note that diverse demographic characteristics do not always mean that the new “diverse” members will have diverse opinions as current board members. For example, directors are inclined to select a demographically different new director who can be recategorized as an in-group member based on his or her similarities to them on other shared demographic characteristics, and such recategorization also increases demographically different directors' tenures and likelihood of becoming board committee members. 44 We also note that board demographic diversity can be detrimental to unity among members, making firms become attractive targets for hostile stakeholders; interestingly, as a result, firms with a more demographically diverse board are more likely to be targeted by activist investors, presumably because boards are unable to form an effective coalition against activist investors. 45

Читать дальше