1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...18 13 13. John G. Ruggie, 1992. Multilateralism: The anatomy of an institution. International Organization, 46(3), 561–98; John Mearsheimer, 1994. The false promise of international institutions. International Security, 19(3), 5–49.

14 14. Neither war nor peace. The Economist, January 25, 2018; Rory Cormac, and Richard Aldrich, 2018. Grey is the new black. International Affairs, 94(3), 477–94.

15 15. Conversation with military officers, Brussels, January 11, 2018.

16 16. Anatoliy Gruzd, and Ksenia Tsyganova, 2015. Information wars and online activism during the 2013/2014 crisis in Ukraine. Policy and Internet, April 27, 2015.

17 17. Thomas Piketty, 2014. Capital in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

18 18. Quoted in: Michel Crozier, Samuel Huntington, and Joji Watanuki, 1975. The Crisis of Democracy. New York: New York University Press. This report also discusses the dismal state of Western democracy.

19 19. Francis Fukuyama, 2014. Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Francis Fukuyama, 2018. Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Patrick Deneen, 2019. Why Liberalism Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; Steven Levitsky, and Daniel Ziblatt, 2018. How Democracies Die. London: Crown.

20 20. Daron Acemoglu, and James Robinson, 2013. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown Business.

OVERTURE

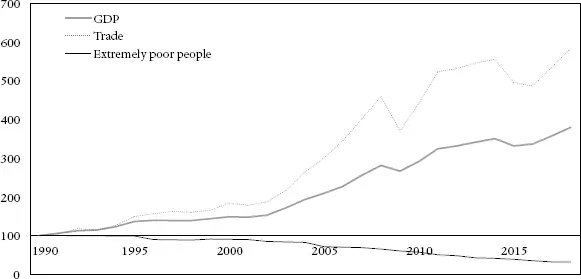

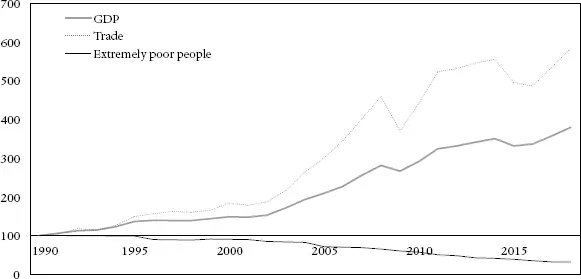

AFTER HAVING READ THROUGH THE INTRODUCTION, SOME READERS might have grown impatient. Why should we question the progress made during the decades that followed the end of the Cold War? In terms of trade, growth, and prosperity, this was a golden age! Indeed, it was so. Just consider figure 1.1. Between 1990 and 2019, world trade increased almost sixfold. Gross production grew fourfold. The number of people living in extreme poverty, below US$1.9 per day, decreased by 70 percent. In absolute terms, the number of very poor people decreased from about 1.9 billion people in 1990 to around 600 million in 2019. One can clearly recognize a few economic dips in the chart; in 2001, for example, in 2009, and in 2015. Yet, each time, the global economy recovered. For all the doomsday preaching, there was no global depression. Despite the dips, recent history remained an upward curve.

Readers might recall the arguments of optimistic thinkers. Steven Pinker described globalization as a cosmic force, born out of the age of enlightenment. 1With some dramatic charts, he argued that globalization improved health, prosperity, security, and wellbeing. This is also the argument that the late Swedish scientist Hans Rosling made in Factfulness . 2His data about receding conflict and advancing wellbeing pop up in numerous presentations of other opinion makers, politicians, and business leaders. Yuval Noah Harari is another acclaimed writer who made the argument that the world has still become a better and more peaceful place. 3This is the moment for humans, he wrote, to move beyond materialistic needs, to use technology to develop their talents, and to emerge like a godlike creature. These optimists are particularly compelling because they advance their case in a seemingly rational and scientific way, supported by loads of data.

Figure 1.1 World development indicators (%)

Note: Trade concerns world exports of goods and services, extremely poor people concerns the estimated number of people living below the US$1.9 PPP per day threshold.

Source: World Development Indicators (WDI).

The aim of this chapter is not to disregard progress. The aim is to put optimistic observations into perspective. We cannot relativize everything. Even if the poverty rate were to be reduced, still hundreds of millions of people would live in destitution. This is a humanitarian tragedy and a security challenge. It suffices, that out of the poor masses a tiny fraction grows angry or opportunistic enough to pick up a weapon, for an entire region to sink into anarchy. Nothing is more devastating to stability than the combination of masses of poor and a few greedy warlords. The data in this chapter call for nuance. Believers in progress should not just look back to see how mankind advanced, but take into consideration the flaws and the errors. The chapter is also a scene setter. It introduces important trends before they are explained in detail in the following chapters. These include the weakening of the West, the limits of globalization, the divergence between China and the rest of the developing world, enduring insecurity, and environmental distress.

Table 1.1. Basic indicators of Western power (%)

Sources: WDI, IMF, SIPRI, UNCTAD.

Note: The West is defined as the United States and Western Europe. “Satisfaction about the state of the country” relates to the US only.

|

1990s |

2000s |

2010s |

| Global population |

13 |

12 |

11 |

| Gross domestic product |

61 |

54 |

48 |

| Manufacturing |

53 |

47 |

34 |

| Satisfaction about the state of the country |

40 |

38 |

26 |

| Export destination |

35 |

33 |

26 |

| Foreign lending |

61 |

82 |

39 |

| Foreign direct investment |

73 |

71 |

51 |

| Military spending |

68 |

65 |

50 |

The weakening of the West

In the 1990s, the West represented 60 percent of the world’s economic production and 50 percent of its manufacturing, with around 13 percent of the world’s population (see table 1.1). In the subsequent decades, that dominance diminished. It coincided with a decrease of public satisfaction with the state of the country (US only) and of trust in politics.

Economic weakening has important external consequences. The smaller a country’s share in the world economy, the more difficult it becomes to wield influence, because partner countries find alternative customers for their exports, alternative lenders, and alternative investors. In the last decade, table 1.1 shows, an average country still had around 26 percent of exports bound for the West, 39 percent of its loans coming from the West, and 51 percent of its foreign investment. The West remained a crucial economic partner. But its position was clearly eroded. This was also true for its military power. The global preponderance enjoyed in the years after the Cold War drew to an end and this relative weakening inevitably empowered other countries as security actors.

Despite economic decline, Western economies were resilient. Trade grew and so did domestic production. But it is clear that economic growth between 2010 and 2019 remained slower than in the previous 20 years (figure 1.2). The resilience of trade, an important element of globalization, did not always coincide with strong production growth. Western countries participated intensively in globalization, but their economies started to grow more slowly. There was also a large gap between globalization and production on the one hand, and the real disposable income of households on the other. The real disposable income is what households can spend, corrected for inflation. If incomes increase, but products and rent become more expensive, the real disposable income increases much more slowly or might even decrease. Particularly the poorest 40 percent suffered. Their real disposable income has had virtually no growth since 2000. Over the 30 years, their real disposable income growth was just 25 percent.

Читать дальше

![Деннис Лихэйн - Когда под ногами бездна [Since We Fell ru]](/books/25722/dennis-lihejn-kogda-pod-nogami-bezdna-since-we-fe-thumb.webp)