The establishment chain is nowadays not deemed an appropriate view of internationalisation processes. Organisations use business contacts and partner networks to collect information and share investment risks. This enables them to develop their international presence at a jump, starting for instance directly with a manufacturing plant in China instead of gradually testing export opportunities. Also, the emergence of “born globals” demands attention, referring to organisations that directly resume their business activities on a global scale as this is a dominant part of their business model (e.g. google). The current scientific landscape is defined by many different theories of internationalisation processes, which all focus on special aspects, for example motives, risk or competition drivers or certain industries. 4Mainly the promotion of the importance of partnerships and networks could be singled out as a common denominator. Although these theories provide interesting insights into trends and patterns, they are not suitable for supporting managerial decisions. Therefore it will be desisted from further discussion.

Not every organisation that establishes routine cross-border activities is already a truly international organisation or even a “global player”. Such a classification would require the extension of the organisation’s management system and processes in a manner that laws and customs of other countries gain a considerable influence on the way the organisation acts. Terms coined for these kinds of organisations include Transnational Enterprise (TNE), Multinational Enterprise (MNE), Multinational Corporation (MNC) or Transnational Corporation (TNC), that are all basically used as synonyms. There are many different definitions mainly based on the aforementioned distinction available. The most widely accepted stems from the UNCTAD and is used for its Transnational Corporation Statistics: “A transnational corporation (TNC) is generally regarded as an enterprise comprising entities in more than one country which operate under a system of decision-making that permits coherent policies and a common strategy. The entities are so linked, by ownership or otherwise, that one or more of them may be able to exercise a significant influence over the others and, in particular, to share knowledge, resources and responsibilities with the others.” 5It is to be noted that this definition does not comprise a specific majority control, although internationally a minimum equity capital stake of 10% or any equivalent including voting power is common. Therefore an exact classification might require selecting the main parent company for a considered associate enterprise, which is usually the one with the highest percentage of ownership. The relevance of TNCs is not derived from mere transnational ownership but instead from the fact that they are considered to be organisations “with formidable knowledge, cutting-edge technology, and global reach” 6. In 2009, the UNCTAD reported the existence of 82.000 TNCs, with 80 million workers employed and their foreign affiliates accounting for a share of 11% in global gross domestic product. 7Additionally, these TNCs can be classified by their transnationality index, that provides information on the relevance of the activities outside an organisation’s home country and is calculated as the average of the three ratios foreign to total sales, foreign to total assets and foreign to total employment. The German Metro AG for example reached 2011 a comparatively high transnationality index of 0,62 and reported 33 countries of operation. 8

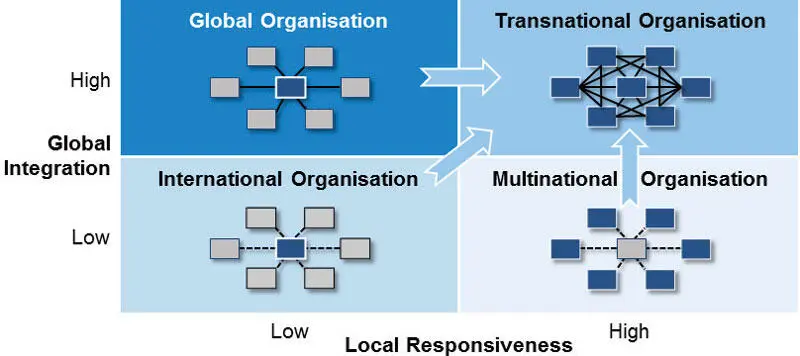

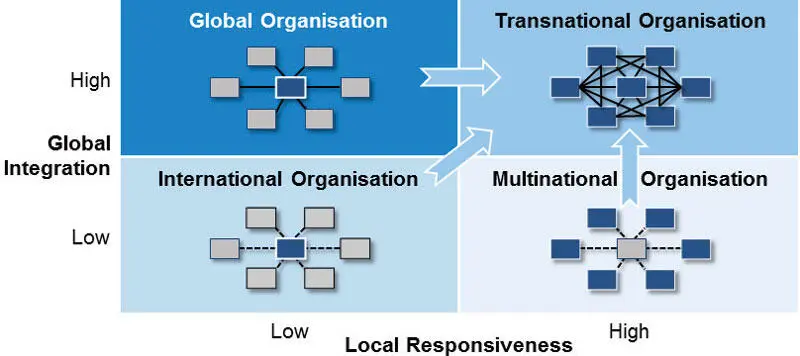

From a scientific perspective, Bartlett and Goshal’s Integration/Responsiveness Framework provides a clear strategic distinction between different kinds of organisations with relevant cross-border activities, as depicted in Figure 1-4. Their portfolio contrasts environmental pressures for global integration with the pressures of local responsiveness as two independent dimensions whose combination of low or high value, respectively, suggest a certain configuration of the organisation. Typical forces for global integration stimulate specific reactions. The importance of multinational customers or competitors (often stimulated by trade liberalisation) combined with high investment intensity for example activates further strategic coordination. Forces like homogeneous tastes and needs, high technological intensity as well as the need for realising cost reductions induce looking for economies of scale, economies of scope, economies of experience and/or worldwide innovation lead to operating integration. The second dimension, pressures for local responsiveness, includes differences in customer needs and tastes, (local) needs for substitutes, individual market distribution structures or host country government demands. In these cases, it is important to assimilate to the special requirements by establishing individual processes for the local environment or by offering local variations of the products or services in order to be attractive for customers and partners alike. 9

Figure 1-4: The Global Integration/Local Responsiveness Framework 10

This Integration/Responsiveness Framework advises upon the choice of a global strategy for organisations facing high global integration pressures (for example due to a strong global competition) but being able to offer a highly standardised product as the pressures for local responsiveness are low. Organisations choosing this approach typically build cost advantages through centrally managed global-scale operations. These global organisations constitute the classic case of a global player, as most of the strategic decisions, responsibilities, resources and assets are centralised in the (home country) headquarters, which exerts a tight control over all overseas operations that deliver the products to a global market. Typical representatives of this kind of organisations are found for example in the aircraft or consumer electronics industry. In contrast, organisations facing low global integration pressures but instead high environmental forcers for local responsiveness follow a multinational (also called multidomestic) strategy approach and are formed as a decentralised federation of independent organisations. Many of their key decisions, responsibilities and assets are decentralised in order to better meet the individual market needs. The relationship between headquarters and subsidiaries is comparatively informal and usually focused on financial control. Multidomestic or multinational organisations are mainly found in industries whose products depend on languages or culture-specific tastes like for example publishing houses, foods and beverages. In cases where both forces contemplated are low, the resulting international organisations are largely based on transferring the products or processes of the parent company to their subsidiaries for worldwide diffusion. Foreign activities are seen as remote outposts that are highly dependent on the headquarters’ resources and support the parent company with their profits. Therefore, the organisation’s management and strategy is oriented towards the home country, exercising a tight control over their foreign subsidiaries but without systematically integrating host country organisations and their perspectives. These organisations are found for example in the textile industry. 11

So far, all introduced strategies are dominated by a single strategic demand. However, in the current global competition organisations increasingly face high forces of global integration and high pressures for local differentiation with a growing emphasis on worldwide innovation. According to Bartlett and Goshal, the appropriate transnational strategy to compete effectively in this extremely demanding environment requires the simultaneous development of “global competitiveness, multinational flexibility and worldwide learning capabilities” 12. Transnational organisations are truly interdependent and make selective centralising or decentralising decisions. Essential resources are centralised within the home country headquarters to protect the core competencies and in part realise economies of scale. Other resources and learning opportunities are geographically dispersed in specialised locations which ensures the necessary flexibility. Products are adapted to local requirements where necessary despite being part of an integrated production process that provides standard components from a single location to all relevant subsidiaries worldwide. Improvements and innovations are promoted in all subsidiaries and headquarters alike and outcomes are shared between all operations and subsequently diffused around the globe. Transnational organisations are characterised by large flows of knowledge, capital, people and products between subsidiaries and between headquarters and subsidiaries. The resulting organisation can be described as an integrated network. The environment described is typical for the telecommunication, pharmaceutical and media industry. More and more industries are gradually developing towards the transnational sector, as is the case for example with the automobile and banking industry. It is obvious that a transnational strategy with its high demands on integration and coordination provides a huge challenge. Therefore, successful examples are rare. 13

Читать дальше